For months Russia’s Vladimir Putin denied planning to attack Ukraine, but on Thursday he announced a “special military operation” in the country’s Donbas region.

The announcement on live television was followed by reports of explosions in Ukraine’s capital Kyiv as well as other parts of the country.

Mr Putin’s latest actions come days after he tore up a peace deal and ordered troops into two rebel-held eastern regions, in his words to “maintain peace”.

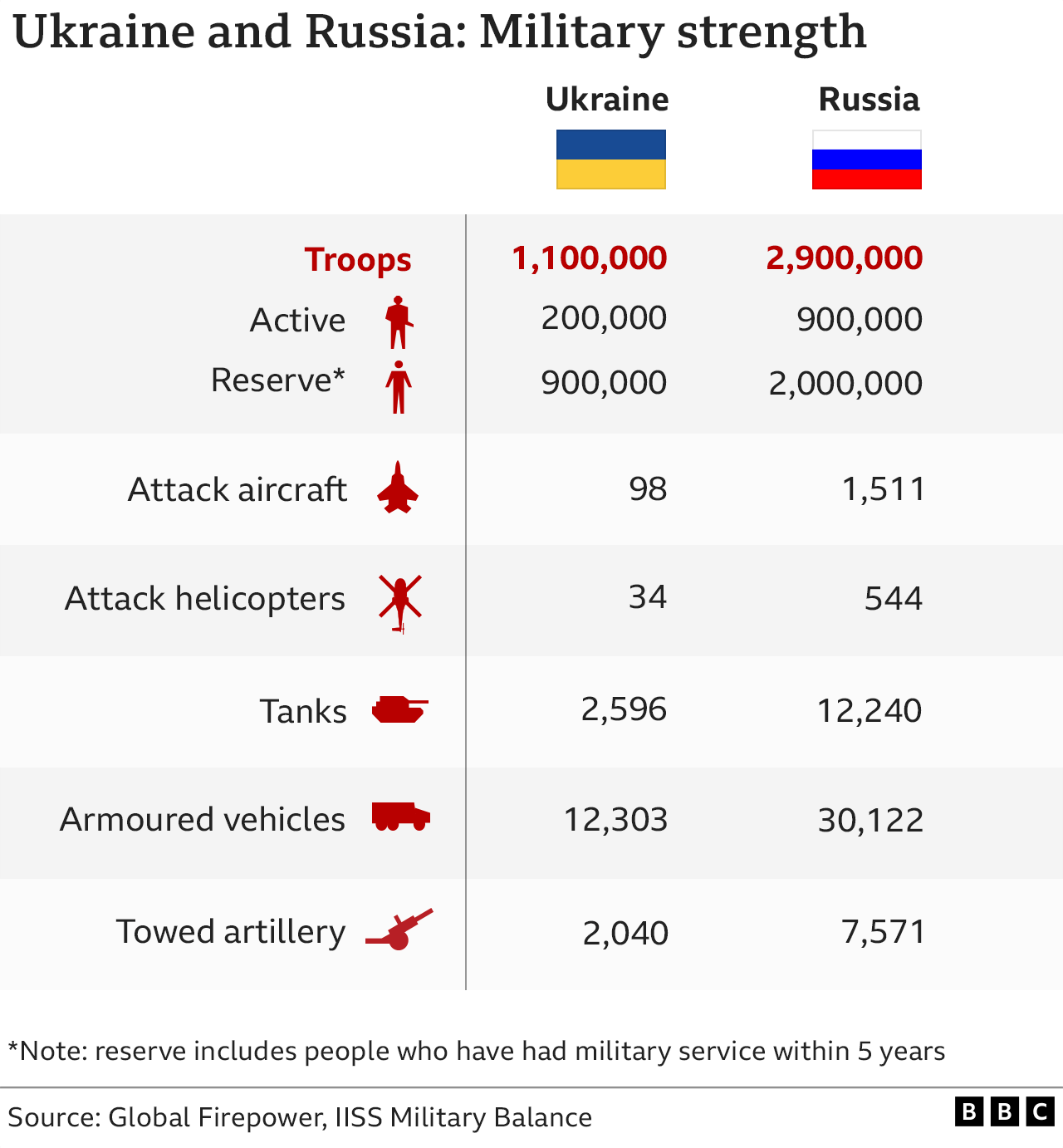

Russia has deployed at least 200,000 troops near Ukraine’s borders in recent months, and there are fears that its latest move marks the first step in a new invasion. What happens next could jeopardise Europe’s entire security structure.

Where are Russian troops being sent and why?

When Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014, rebels backed by President Putin seized big swathes of the east and they have fought Ukraine’s army ever since.

There was an international Minsk peace accord but the conflict continues and so Russia’s leader says he is sending in troops into two rebel-held areas. The UN Secretary-General has categorically rejected Russia’s use of the word peacekeepers.

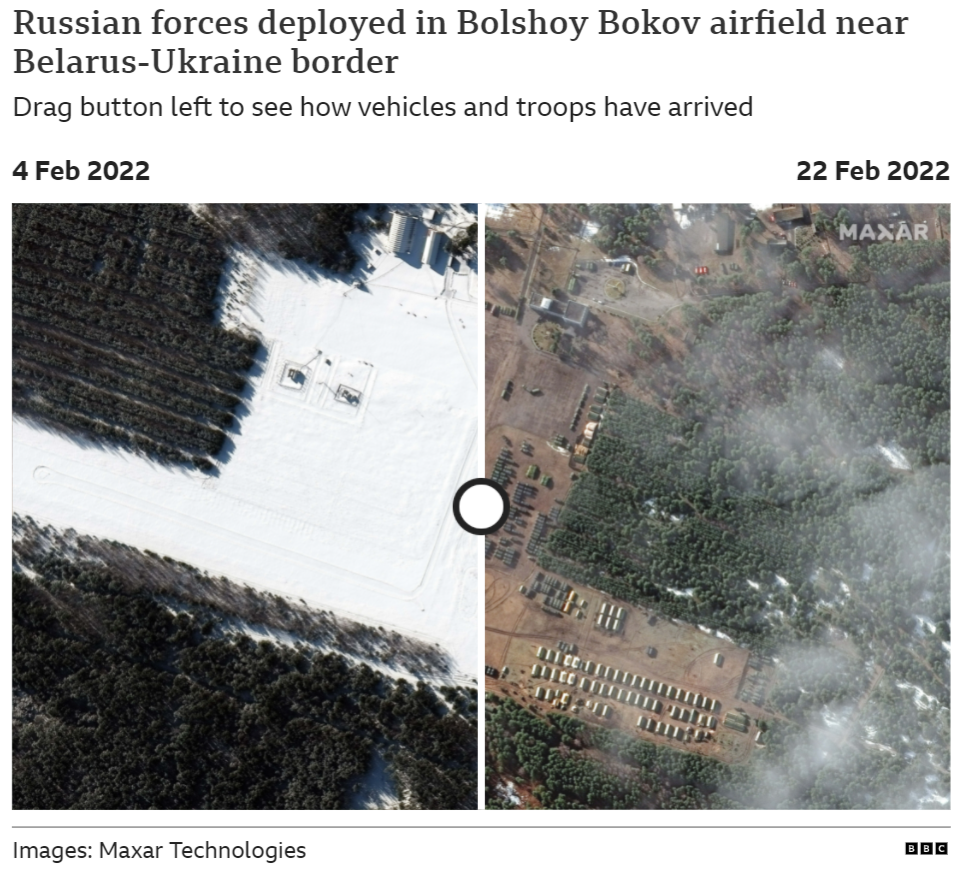

The West believes Moscow is planning an imminent, new invasion of Ukraine, a country of 44 million people bordering both Russia and the European Union. For a start, there are reports of tanks arriving in separatist-controlled Donetsk and the latest satellite photos show Russian troops deployed within a short distance of Ukraine’s borders.

President Putin warned Ukraine it would be responsible for further bloodshed if it did not halt hostilities in the east. But there have already been a series of bogus incidents and any one of them could be used as a pretext for a Russian attack.

What’s Putin’s problem with Ukraine?

Russia has long resisted Ukraine’s move towards European institutions, both Nato and the EU. Now, Mr Putin has claimed Ukraine is a puppet of the West and was never a proper state anyway.

He demands guarantees from the West and Ukraine that it will not join Nato, a defensive alliance of 30 countries, and that Ukraine demilitarise and become a neutral state.

As a former Soviet republic Ukraine has deep social and cultural ties with Russia, and Russian is widely spoken there, but ever since Russia invaded in 2014 those relations have frayed.

Russia attacked Ukraine when its pro-Russian president was deposed in early 2014. The war in the east has since claimed more than 14,000 lives.

Why is recognition of rebel areas dangerous?

Until now these so-called people’s republics of Donetsk and Luhansk have been run by Russian proxies.

Under Mr Putin’s decree recognising them as independent, Russian troops are for the first time recognised as stationed there and they can build military bases too.

By pouring Russian troops into an area witnessing hundreds of ceasefire violations every day, the risk of open war becomes far higher. The two rebel areas would have had special status within Ukraine under the Minsk peace accords, but Mr Putin’s move bars that from happening.

What makes the situation more alarming is that the two rebel statelets do not just claim the limited territory they hold, they covet all of Ukraine’s Donetsk and Luhansk regions. “We recognised them, didn’t we, and this means we recognised all of their founding documents,” said the Russian leader.

Russia has already prepared the ground for war, with false accusations that Ukraine committed “genocide” in the east. It has handed out more than 700,000 passports in rebel-run areas, so any action could be justified as protecting its own citizens.

How far will Russia go?

President Putin may stop at tearing up the peace accords in the east. He has in the past only spoken of “military-technical” measures if he does not get what he wants and Moscow previously insisted “there is no Russian invasion”.

But the chances of a diplomatic solution do not look good and the West fears he will go further. US President Joe Biden has warned: “We believe they will target Ukraine’s capital Kyiv, a city of 2.8 million innocent people.”

In theory, Russian forces could aim to sweep across Ukraine from the east, north and south and try to remove its democratically elected government.

They could mobilise troops in Crimea, Belarus and around Ukraine’s eastern borders.

But Ukraine has built up its armed forces in recent years and Russia would face a hostile population. The military has called up all reservists aged 18-60.

Top US military official Mark Milley said the scale of Russian forces would mean a “horrific” scenario with conflict in dense urban areas.

Russia’s leader has other options too: perhaps a no-fly zone or a blockade of Ukrainian ports, or moving nuclear weapons to neighbouring Belarus.

He could also launch cyber-attacks. Ukrainian government websites went down in January and two of Ukraine’s biggest banks were hit in mid-February.

What can the West do?

The West says Russia’s move is illegal and UN Secretary-General António Guterres has condemned it as a violation of Ukraine’s territorial integrity and sovereignty.

But Nato allies have made clear there are no plans to send combat troops to Ukraine itself. Instead they have offered Ukraine advisers, weapons and field hospitals.

So the chief response will be penalising Russia with sanctions:

- Germany has halted approval on Russia’s completed Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, a major investment by both Russia and European companies

- The EU has agreed broad sanctions that include 351 MPs who backed Russia’s “illegal decision” to recognise the rebel-held regions as independent states in parliament

- The US says it is cutting off Russia’s government from Western financial institutions and targeting high-ranking “elites”

- The UK is targeting five major Russian banks and three billionaires.

Bigger sanctions are being kept in reserve.

The US is looking at Russia’s financial institutions and key industries; the EU is focusing on Russian access to financial markets and the UK has warned “those in and around the Kremlin will have nowhere to hide”, with restrictions imposed on Russian business accessing the dollar and pound.

The ultimate economic hit would be to disconnect Russia’s banking system from the international Swift payment system. But that could badly impact the US and European economies.

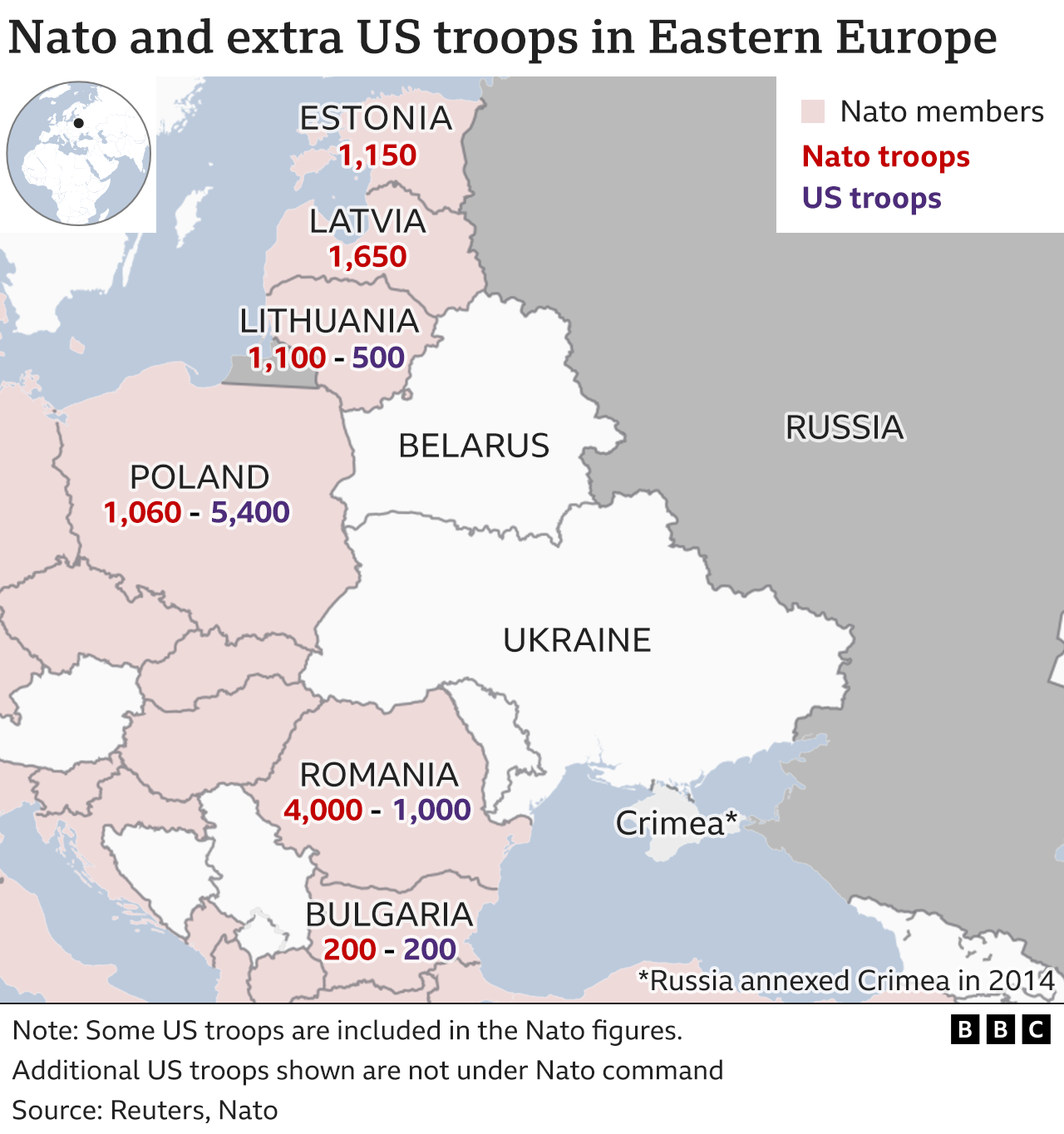

Meanwhile, 5,000 Nato troops have been deployed in the Baltic states and Poland. Another 4,000 could be sent to Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary and Slovakia.

What does Putin want?

Russia has spoken of a “moment of truth” in recasting its relationship with Nato and has highlighted three demands.

First, it wants a legally binding pledge that Nato will not expand further. “For us it’s absolutely mandatory to ensure Ukraine never, ever becomes a member of Nato,” said Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov.

Mr Putin has complained Russia has “nowhere further to retreat to – do they think we’ll just sit idly by?”

In 1994, Russia signed an agreement to respect independent Ukraine’s independence and sovereignty.

But last year President Putin wrote a long piece describing Russians and Ukrainians as “one nation”, and now he has claimed modern Ukraine was entirely created by communist Russia. He sees the collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991 as the “disintegration of historical Russia”.

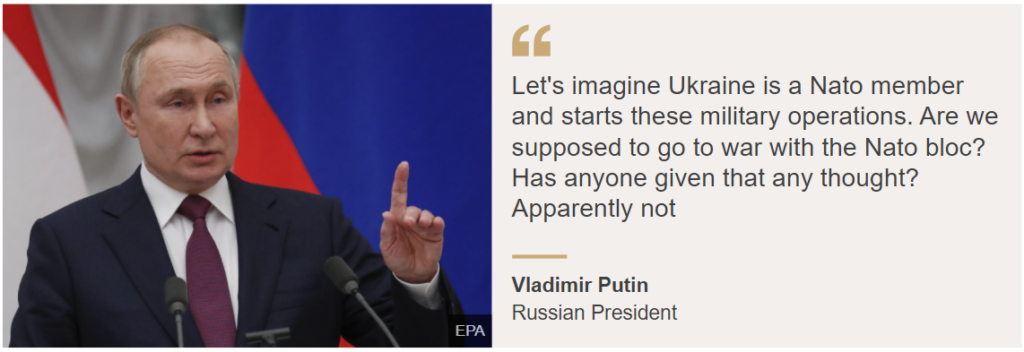

President Putin has also argued that if Ukraine joined Nato, the alliance might try to recapture Crimea.

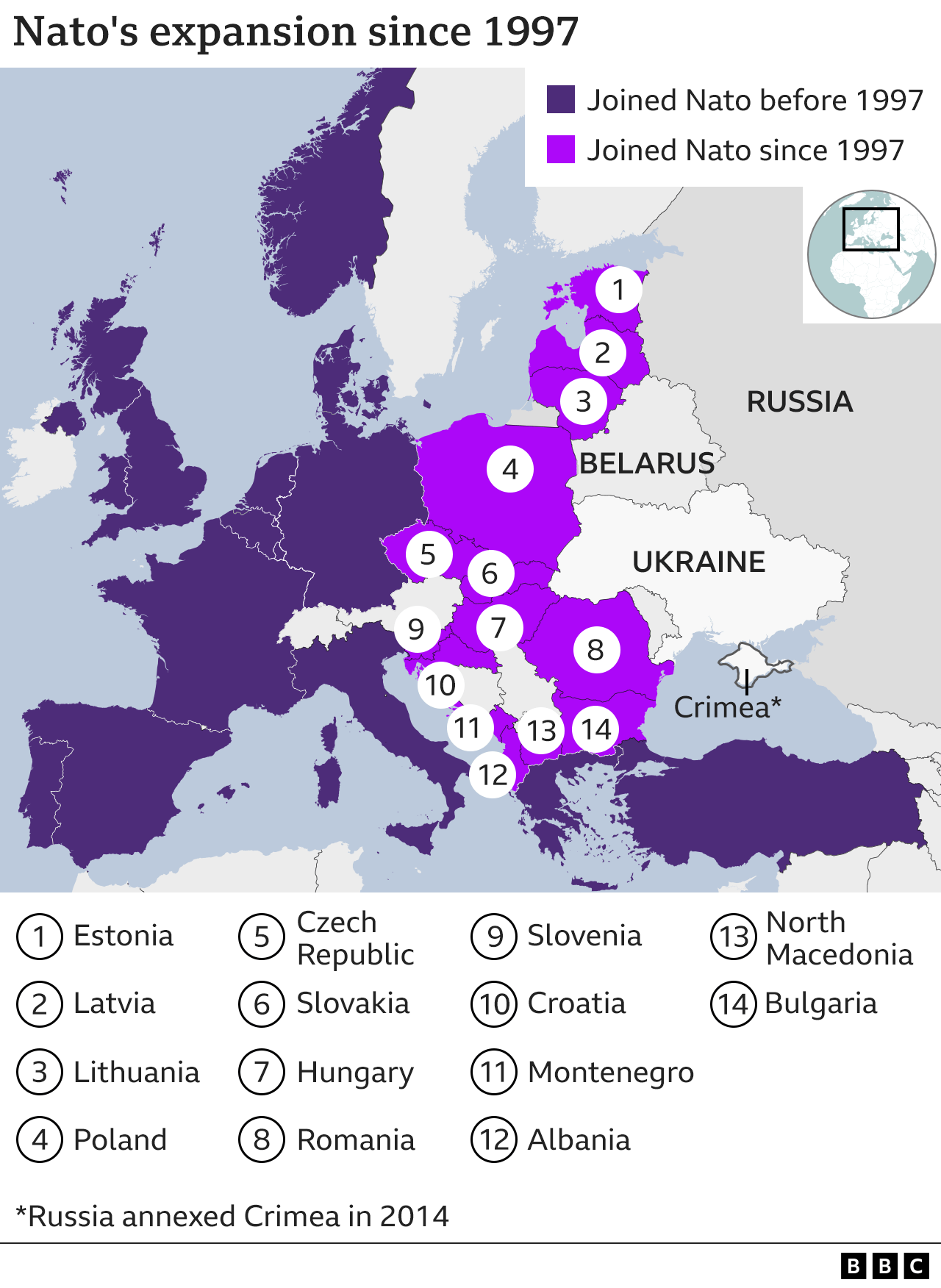

His other core demands are that Nato does not deploy “strike weapons near Russia’s borders”, and that it removes forces and military infrastructure from member states that joined the alliance from 1997.

That means Central Europe, Eastern Europe and the Baltics. In reality Russia wants Nato to return to its pre-1997 borders.

What has Nato said?

Nato is a defensive alliance with an open-door policy to new members, and its 30 member states are adamant that will not change.

Ukraine’s president has called for “clear, feasible timeframes” to join Nato, but there is no prospect of it happening for a long time, as Germany’s chancellor has made clear.

The idea that any current Nato country would give up its membership is a non-starter.

In President Putin’s eyes, the West promised back in 1990 that Nato would expand “not an inch to the east” but did so anyway.

That was before the collapse of the Soviet Union, however, so the promise made to then Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev only referred to East Germany in the context of a reunified Germany.

Mr Gorbachev said later “the topic of Nato expansion was never discussed” at the time.

Is there a diplomatic way out?

Apparently not for the moment, as France and the US have cancelled planned talks with Russia’s foreign minister. But both France and Germany say the possibility of dialogue is open.

Any eventual deal would have to cover both the war in the east and arms control.

The US had offered to start talks on limiting short- and medium-range missiles as well as on a new treaty on intercontinental missiles. Russia wanted all US nuclear arms barred from beyond their national territories.

Russia had been positive towards a proposed “transparency mechanism” of mutual checks on missile bases – two in Russia, and two in Romania and Poland.