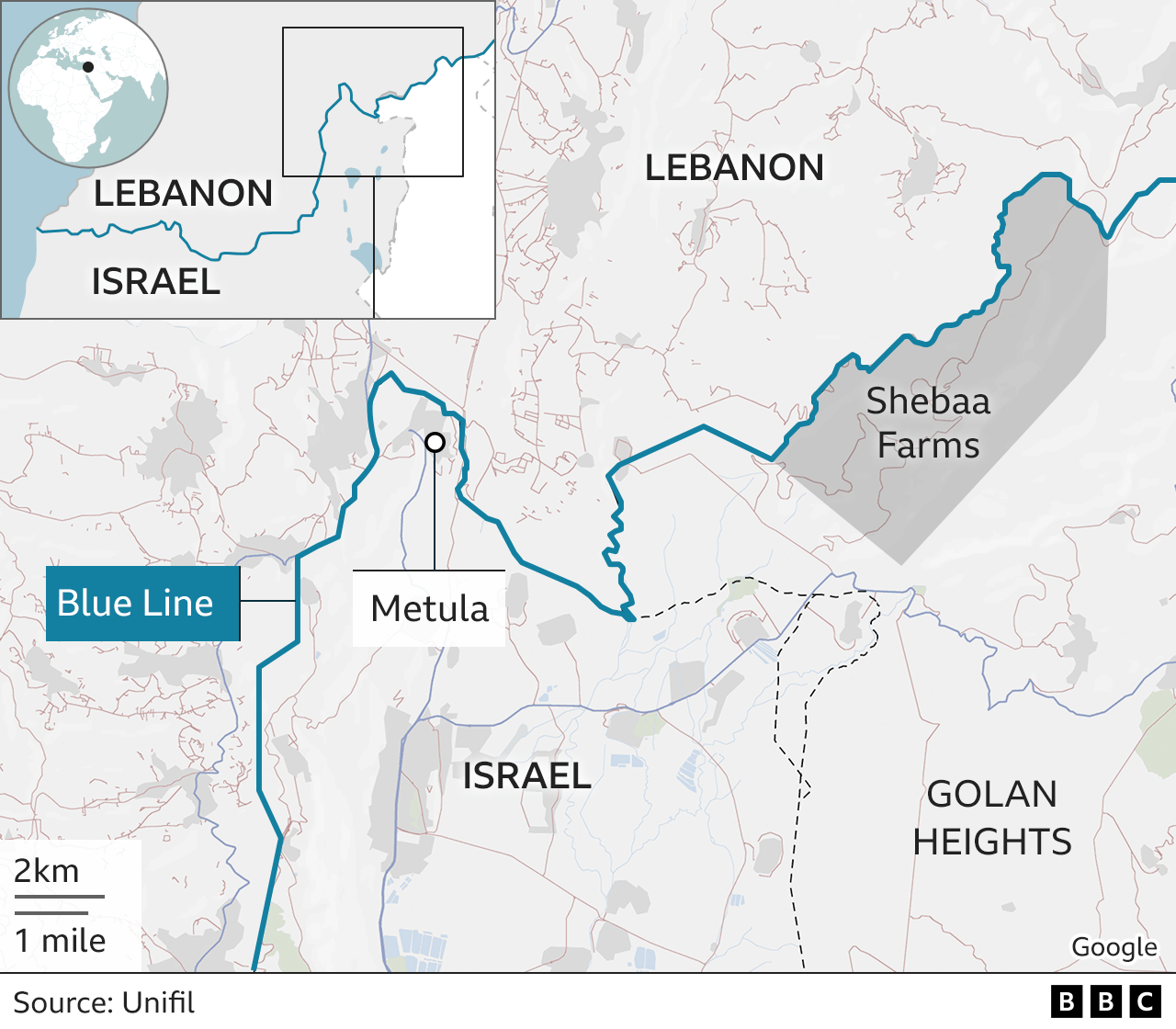

It is a lonely drive to Israel’s most northern town, Metula, along a spur of land that is surrounded on three sides by Lebanon.

That means it is also surrounded on three sides by Lebanon’s most powerful armed group, Hezbollah.

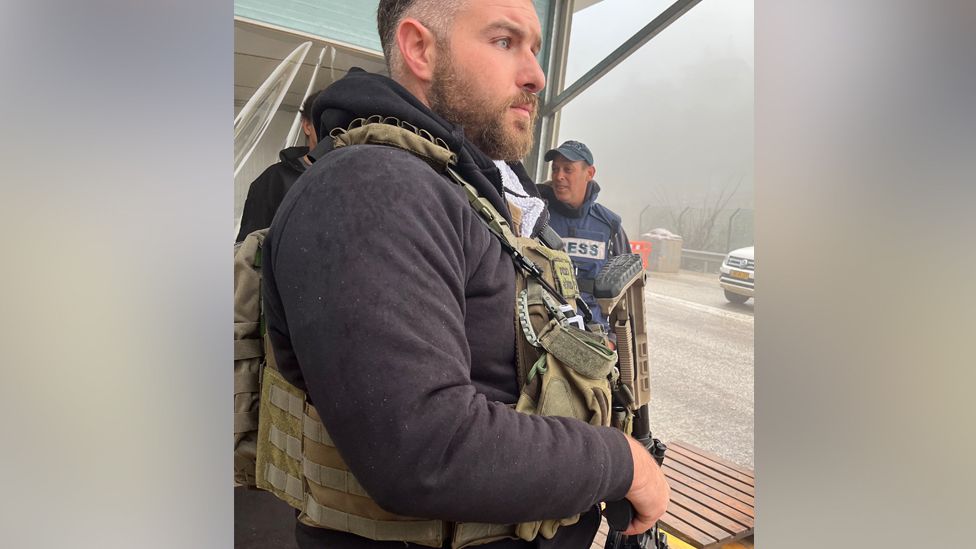

The soldiers at the checkpoint on the edge of Metula were all local men, mostly middle-aged reservists with no illusions about the force on the other side of the border.

As the rain lashed down on a miserable, foggy night, one of them, who did not want his name to be published, used his finger to traverse the compass, pointing to the border and Hezbollah’s positions.

“To the west a quarter of a mile, to north half a mile and another half mile to the east. So, we are 300 degrees surrounded by the Hezbollah.” The other 60 degrees, he said, included the steep road back down to the rest of Israel.

The Gaza war that started after Hamas attacked on 7 October, killing around 1,200 Israelis, mostly civilians, has been devastating. The Israeli offensive that followed has, so far, killed well over 27,000 Palestinians, mostly civilians, and inflicted severe damage on Gaza.

The border conflict between Israel and Hezbollah that followed has steadily intensified, but all sides know how much worse it would get if it exploded into a high-intensity war. It was stark and clear to the men on guard on the edge of Metula.

The Israeli reservist continued: “Yes, it definitely can turn into a big war and a big war with Hezbollah is not like Hamas, they are a real army, very trained, greatly equipped and they have a lot of experience, real experience in Syria.” Hezbollah intervened in the war in Syria, fighting for the regime of President Bashar al-Assad.

The US secretary of state, Antony Blinken, has no plans to visit Metula on his current Middle East tour, but the long flight from Washington and the travelling times between different capitals in the Middle East must be grimly familiar to him by now. He is back in the region for the fifth time since 7 October.

Mr Blinken has not tried to minimise the magnitude of the crisis in the Middle East. At the end of January, standing next to the secretary general of Nato, he said it was “incredibly volatile… I would argue that we have not seen a situation as dangerous as the one we’re facing now across the region since at least 1973, and arguably even before that.”

That is quite a comparison.

The Middle East war of 1973 turned into one of the most dangerous superpower confrontations of the Cold War. With US President Richard Nixon submerged by the Watergate scandal, his Secretary of State Henry Kissinger ordered US strategic forces on to their highest level of peacetime alert, Defcon 3, after a report that the USSR was moving nuclear weapons to the Middle East.

Half a century on Mr Blinken was speaking after militias trained and funded by Iran killed three American soldiers at a base in Jordan. Since then the US, helped in Yemen by the UK, has started a rolling campaign of retaliatory air strikes. The Americans hope they have calibrated their response to stabilise matters, not make them worse, but that is not at all certain.

Hawkish critics of President Biden in Washington DC say that action taken so far will not deter Iran, which backs Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Houthis in Yemen as well as Shia militias in Syria and Iraq. The hawks say only attacks on Iran itself will force Tehran to order its proxies and allies to stand down. The Biden administration believes attacking Iran itself risks detonating a wider conflict in the Middle East.

On previous trips Secretary Blinken has repeatedly expressed America’s support for Israel’s war against Hamas, but also grave doubts about the way Israel is fighting. Washington has called, unsuccessfully, for restraint. The US has continued to supply Israel with the weapons it needs for its campaign, despite its reservations about the way they are being used.

The US has had more success in forcing Israel to let in much more humanitarian aid to more than two million Palestinian civilians who are trapped in the catastrophe. Last October, Israeli leaders said nothing would be allowed in. Even so, the UN and aid groups active in Gaza say Israel has not allowed in anything close to what they need.

Hardened aid officials with long careers trying to help civilians in warzones have told me they have never seen anything as bad. One who has been inside Gaza multiple times in the last few months (journalists are not allowed in by Israel and Egypt, who control the borders) said he had “never seen anything of this size, scale and depth”.

Mr Blinken’s top priority is securing a ceasefire in Gaza. President Biden needs to calm the Middle East, not just because of the terrible risks of a continued and escalating war, but because he faces elections this year. Polls suggest he is losing votes as some Americans blame his support for Israel for the humanitarian catastrophe inside Gaza.

A renewed burst of diplomacy, involving the US, Qatar, Egypt and Israel, produced broad parameters for a deal but no details.

Hamas has delivered its terms. It wants a three-stage process lasting 135 days, which would allow a phased exchange of hostages for Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails. It has put forward a long list of demands. The most significant is that by the end of that time Israel would have pulled its forces out of Gaza and the war would be over.

All that was dismissed by Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu after his meeting with Secretary of State Blinken.

Since the war started, Israel has defined victory as the destruction of Hamas and the safe return home of the hostages. Neither objective has yet been achieved. Mr Netanyahu said Israel would not make concessions to Hamas, and repeated his insistence that its forces were closing in on “total victory”. In recent days, he has also said Israel needed to kill Hamas leaders.

Mr Blinken still believes, he said later, that a deal is possible. His challenge is to try to narrow the gap between the diametrically opposed positions of Israel and Hamas to get some sort of ceasefire.

The BBC’s information is that Hamas is much less confident than it was early in the war. The ferocity of Israel’s assault and the killing of so many civilians means that Gazans trapped in the war are turning against Hamas, making its leaders realise they need to try negotiation.

In Israel, for all the determined talk emerging from the prime minister and his allies, pressure is growing for a ceasefire to create an opportunity for a deal to get the hostages back.

It is not much for Mr Blinken to work with. The odds look to be against a ceasefire unless either or both sides make substantial concessions.