Former Ambassador to the United Kingdom, Victor Smith, has told the story – as he says was told him privately by former president Jerry John Rawlings – about how the Americans forced the late Ghanaian military leader to return the West African nation to democratic rule after having led a junta for eleven years.

Rawlings’ Coup History

Mr Rawlings was a 32-year-old Ghanaian air force officer when he first attempted to overthrow what he considered a corrupt national government in May 1979.

He was jailed but soon became a hero to the country’s poor people and military.

With the help of disaffected soldiers and non-commissioned officers, he escaped from jail on June 4, 1979, then proceeded to a radio station to urge his followers to seize power.

By the end of the day, the country’s military leader, Frederick Akuffo, had been toppled.

Mr Rawlings, who was often known as “Flight Lt. Rawlings” for his military rank, charged Akuffo’s regime with corruption and profiteering.

“The rich became richer, including the high military officers, and most of us were starving,” he said at the time. “I’ve always wanted to do something to correct injustice.”

A presidential election was already scheduled, and Mr Rawlings vowed to step aside in favour of the new democratically elected leader.

But during his 112 days in power, he oversaw the hasty creation of military tribunals that put Akuffo and two other former heads of state on trial.

They were executed, along with numerous high-ranking officials.

True to his word, Mr Rawlings and other coup leaders returned to their military positions when Ghana’s new president, Hilla Limann, was sworn into office.

In a speech before the country’s parliament, Mr Rawlings looked directly at Limann and issued an unmistakable warning.

“If people in power use their offices to pursue self-interest, they will be resisted and unseated,” he said, before ominously adding, “We have every confidence that we shall never regret our decision to go back to the barracks.”

In 1957, Ghana became Africa’s first sub-Saharan country to declare independence from a colonial power, in its case, Great Britain.

After Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, was overthrown in a military coup in 1966, the country faced increasing poverty and unrest under a series of military and civilian leaders.

That trend continued during Limann’s first two years in office, as Mr Rawlings travelled throughout the country, giving speeches to large crowds and denouncing what he called the “rottenness” of a system that “would permit those same corrupt forces to retain their hold on Ghanaian life.”

Limann mocked Mr Rawlings as “that boy,” and others maligned his interracial parentage, calling him “half African.”

On December 31, 1981, Mr Rawlings led a second coup, calling Limann and his supporters “a pack of criminals who bled Ghana to the bone.”

This time, Mr Rawlings had no intention of relinquishing authority.

He dissolved the country’s parliament, abolished the constitution and banned all political parties except his own.

He aimed to establish a socialist state in Ghana, espousing admiration for Libya and its dictator Moammar Gaddafi.

“I am prepared at this moment to face a firing squad if what I try to do for the second time in my life does not meet the approval of Ghanaians,” Mr Rawlings announced at the time.

In 1992, after more than 10 years of a one-man rule, Mr Rawlings ran for election and won the presidency with 58 percent of the vote.

How The US Forced Rawlings To Return Ghana To Democracy

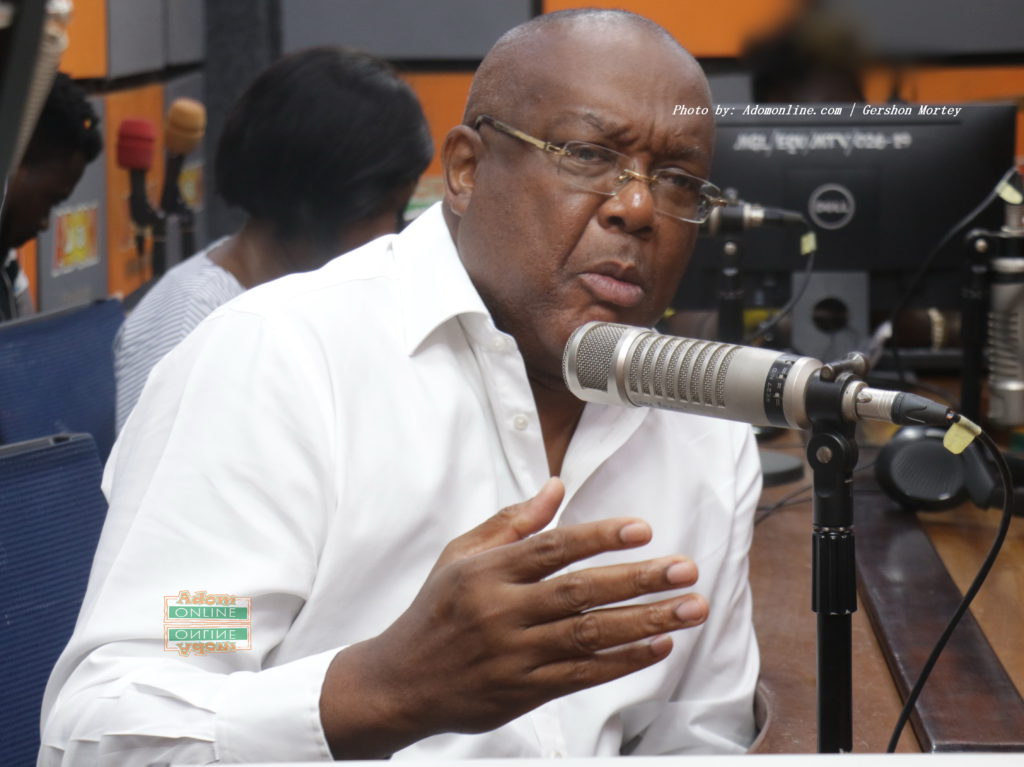

Speaking in a one-on-one interview on CTV to mark the first anniversary of Mr Rawlings’ death, his former aide, in answering a question about whether he thought Mr Rawlings’ return of the country to constitutional rule was premature, Mr Smith said: “Did he have a choice?”

“I don’t think so because that’s what he [Rawlings] told me.

“I asked him one day that: ‘It looks as if you’re showing interest in the way things are being done in the country again – this is [a conversation] outside office when we were working together – and, so, asked him: ‘Then why did you hand over?’ This is in a private conversation. ‘If you’re now beginning to show interest, was it the case that you got tired and that you should have taken some leave just to renew your desire to continue with the good work you were doing?’ And, he said: ‘Did I have a choice?’ And I said: ‘What do you mean by did you have a choice?’ He said: ‘I was not given a choice’.”

Mr Smith continued: “He [Rawlings] had a visitor; one day, he said he was at the air force station going for a flight and, I think he was told that the US ambassador and an emissary from the State Department needed to see him.

“So, he came back to the castle and he sat down with these two gentlemen and the ambassador introduced the gentleman and the ambassador left the room”.

“Then, the other gentleman gave him [Rawlings] a letter. He opened it and looked at it and was trying to ask the gentleman questions. And, the guy was like: ‘I’m not to discuss this matter’.”

“Simply put, the letter said: ‘Prepare the country for democratic rule’. ‘He was not supposed to discuss it with you; he was supposed to hand it over to you to read’. I said: ‘Really?’ He said: ‘Yes’.

“So, at that point in time, he knew that the Americans had done it before; we all know they played a certain role in Nkrumah’s overthrow, so, if they’ve started to say that: ‘Prepare the country for democracy’, it’s either other people have gone to the Americans – and we know who went to the Americans to try and push for democratic rule – that is not to suggest that he didn’t want democratic rule but he wanted to see this country progress and transform quicker than … we were slow”, Mr Smith recounted.