In less than a year, a camp in northern Uganda has taken in more refugees than any other in the world, and all of them from war-torn South Sudan.

Here in Bidi Bidi it can take you one hour to drive from one end of the camp to the other. But it is not what you might envisage.

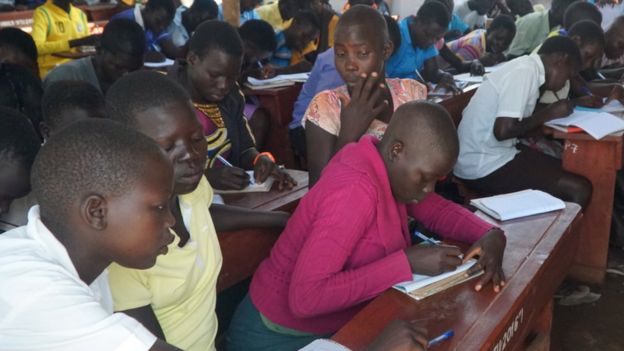

Much of this place is lush, green and fertile. South Sudanese are given a plot of land to build a home and farm. They live next to Ugandans, fetch water together and their children go to the same schools.

Most of the area is government-owned but some Ugandans have chosen to give part of their land to refugees, like 61-year-old Issa Agub.

It is getting late when we arrive at his compound and his family is preparing porridge and beans over a firewood stove to break their Ramadan fast.

“I gave this land because the refugees are already here. I don’t see them as strangers I see them as brothers. When I run out of food, they’ll be the first people I turn to for help.”

Mr Agub says he cannot be sure how much land he owns but says he is helping 10-15 families.

According to the UN and other international organisations, Uganda has progressive laws towards refugees.

The foundation for these policies was laid soon after the country’s independence in 1962. At the time, thousands of ethnic Tutsis were fleeing genocide in neighbouring Rwanda and coming to Uganda.

A new law was passed, the Control of Alien Refugees Act, which protected people fleeing persecution, gave refugees the right to work and created the first gazetted settlements or camps.

Since then the legislation has been updated and policies strengthened. Over the decades conflicts in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Somalia, Kenya and South Sudan have meant a constant stream of refugees into the country.

Many Ugandans have also had to flee their country because of conflict and know what it is like to be destitute.

But the scale of the challenge today is like no other many here have faced. Since July, more than 700,000 South Sudanese have arrived.

MP Hassan Kaps Fungaro says communities have been overstretched.

“There is pressure on the resources on the ground. In the market, prices have gone up,” he says.

“UN trucks bringing food have damaged our roads beyond recognition. UN and government jobs are being given to people who are not from the area.”

Protests have taken place over access to jobs for local youths. And many complain about the damage to the environment as trees were cut to make way for the refugees or firewood.

At least two South Sudanese refugees told us that women had been stopped from collecting firewood.

But Mr Fungaro and others will tell you they do not want the refugees to be chased away.

Near Mr Agub’s home a Ugandan couple – Joyce Anguko, a teacher and Geoffrey Aluma, a counsellor – are busy digging.

They have come here from a nearby town. They could not find land there to grow crops and just like the new arrivals from across the border, Mr Agub has given them a small patch of land.

Are they resentful of the South Sudanese refugees who are getting free plots of land?

Mr Aluma says: ‘There is not much competition. People here are very hospitable because at one time we were refugees in South Sudan. They hosted us until there was peace in Uganda.”

Aid agencies and the government meanwhile say they are seriously short of funds to look after all of those in need.

A pledging conference is taking place in Uganda to raise $2bn (£1.5bn) for the emergency response.

Hunger is a common complaint as food rations were cut by half to 6kg (13lb) per person.

Elias Kandus Emmanuel is the head teacher at Koro Highland Primary School in Bidi Bidi.

“The young children do not attend classes. They come from home hungry, they doze in the classes and they even leave early.”

The refugees we spoke to told us they want to go back, where they can have better control of their destiny.

After all, home is home. Uganda is generous and open but this a sticking plaster – the real solution is an end to war in South Sudan.