A first of its kind

A few days ago, the government of Ghana launched at a lavish ceremony a facility that it called, “Ghana’s first commercial gold refinery”. At the event, the country’s leaders described the moment as destiny-changing; centuries of exporting raw gold was finally at an end. The hour of “value-addition” has struck! Extreme efforts went into getting the international press to amplify the message. AFP, the global French news agency, even went as far as calling it the “first of its kind in West Africa“.

Strange Misinformation

Shockingly, the refinery, housed inside Diamond House, seat of the country’s state-owned jeweler, the Precious Minerals Marketing Corporation (PMMC), is neither Ghana’s first commercial gold refinery nor even the largest and most sophisticated. Stunned by the brazen misinformation, I took to X (formerly Twitter) immediately to straighten things up.

At least three major commercial gold refineries predated the Royal Ghana Gold Refinery, as this latest one is called. As I explained on X, the first to come to my notice was Asap Vasa Company Limited, with a capacity to refine 100 kilograms of gold a day, opened in 2013.

But, in truth, there was an aborted attempt to set one up even earlier in 2011. Years later, in 2016, financial close was reached and that project came online as Gold Coast Refinery.

Gold Coast Refinery, established near Accra’s international airport by Ghanaian-Egyptian construction company, Euroget, by virtue of having the capacity of refining 480 kilograms of gold a day, is actually the largest refinery of its kind in Ghana (and possibly even West Africa, as it likely outstrips Nigeria’s Dukia Gold), not Royal Ghana Gold Refinery (400 kilograms a day). It was also the first refinery to produce fully standardised “hallmarked” gold bars in line with LBMA rules.

Whilst Gold Coast Refinery was still in the wilderness of financial planning, Sahara Royal Gold Refinery (200 kilograms a day capacity) was launched in Accra.

These players are merely the ones whose launch was, on each occasion, heralded by senior government officials as marking a new stage of local value addition in the gold sector. There are several other specialty refineries in the country, such as Helvent Holdings, Sewia, AA Minerals, Goldstrom, etc, which are actually the ones often preferred by artisanal gold miners and small-scale traders.

Truth be told, the bigger, more sophisticated, players like Sahara Royal and Gold Coast have mostly been lying idle, in some years refining and exporting zero kilograms of gold. So also has the latest big boy on the block, Royal Ghana. Since technical commissioning in November 2021, customs records show that it has barely exported any refined gold. The problems facing such refineries are rather straightforward and outlined in broad strokes in my tweet. They deserve serious policy attention, not PR. In future commentary, I may flesh out the issues. Right now, though, I am more interested in Royal Ghana’s launch.

Why such twisted PR?

Why would the government launch a refinery smaller and less sophisticated than some refineries already operational in the country, and struggling to get gold to refine, with such fanfare? And even go further to pump resources into PR to create the impression that something groundbreaking and country-transforming has happened?

The innocuous answer is that Ghana is on the brink of general elections on 7th December 2024, and the ruling party just wanted a nice feel-good story for the electorate. An even more optimistic answer is that this refinery has 20% state ownership, is in a direct joint venture partnership with state-owned PMMC, and has been positioned to refine local gold purchased by the Bank of Ghana to boost its reserves. Hence, it is no ordinary commercial refinery.

One could excuse the outright falsity in the way the project was presented if the above explanations carry weight, except that they actually raise more intriguing questions.

Reading into Motives

Before Royal Ghana came into the picture, Gold Coast Refinery had been discussing a strategic partnership with the government for many years. Having spent nearly five times more money on its refinery than Royal Ghana’s promoters have on theirs, Gold Coast’s investors were just as willing to offer the government carried interest if assurances could be given that local gold miners would be compelled or induced to use it in some fashion before exporting their gold.

As mentioned in my tweet, the large-scale miners prefer to maintain existing contracts and relationships with LBMA-certified refineries like Rand in South Africa to ensure that they can preserve current international trading channels. Forcing these companies to use a local refinery would require that such a refinery acquires LBMA certification (or perhaps from another major certifier, such as COMEX or Shanghai Futures) in order to be able to export globally recognised hallmarked bars. Such certification programs, however, have strenuous rules on capitalisation, minimum annual output track record, and a whole host of reputational and other due diligence markers. Suffice it to say that no refinery in Ghana meets these requirements for now.

That makes the use of regulatory fiat more suitable for the small scale gold sector, especially in relation to the Bank of Ghana’s own gold purchasing program. Whichever refinery can secure government support to become the place where small scale gold producers, and maybe eventually even the big mines, have to send their dore (raw) gold to be refined from the 92% – 96% range to the 99.9% range will become the market winner. It would seem that Royal Ghana Gold Refinery has won that contest. But how?

As previously indicated, Gold Coast Refinery have spent years lobbying for the same strategic relationship with the government. It has invested more capital and been around for much longer. How did Royal Ghana overtake it to win this prize, and why is the government so keen to celebrate the latter with such pomp and pageantry? Even going to the extent of feeding international press outlets with outright misinformation?

State Enchantment yet again

Whenever something of this nature doesn’t add up in Ghana, I turn to my theory of “State Enchantment“. Whenever you see the Ghanaian government working itself up into a frenzy to describe some project in superlative terms as fulfilling some glorious destiny for the country, you can rest assured that they are trying to deflect attention from a closer look at the underlying commercial relations and objectives of whatever it is that has been packaged as a “national redemptive project”. Yes, state enchantment, or jujufication, if you will.

Just as state enchantment is what is at play when the government denies the existence of credit scoring institutions in the country just so it can soften the ground to launch a new one owned by politically connected players, it is the same principle at work when existing refineries are denied existence so that some kind of monopolistic advantage can be conferred on a newcomer.

Knowing the pattern quite well now, there are no prizes for guessing that I dug deep into Royal Ghana Gold Refinery with understandable suspicion as soon as I saw the usual signs. What I found wasn’t too reassuring.

Enter yet another hollow investor

Royal Ghana, as mentioned earlier, is a joint venture between Rosy Royal Minerals Limited and state-owned PMMC.

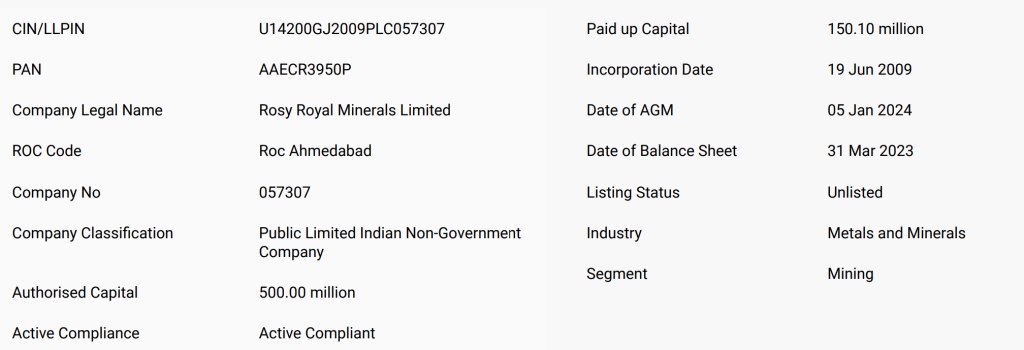

Rosy Royal is an Ahmedabad (India) – based mining company, 99% owned by Murtaza Samiwala, with registered share capital of less than $1.8 million and authorised capital of less than $6 million.

Intriguingly, it has no experience whatsoever in sophisticated gold refining at all. Nestled in a small unmarked corner of a non-descript building in one of Ahmedabad’s less fashionable districts (since vacating a better location shared with Zinzuwadia Jewelers), it specialises in stone quarrying for tiles production, not gold.

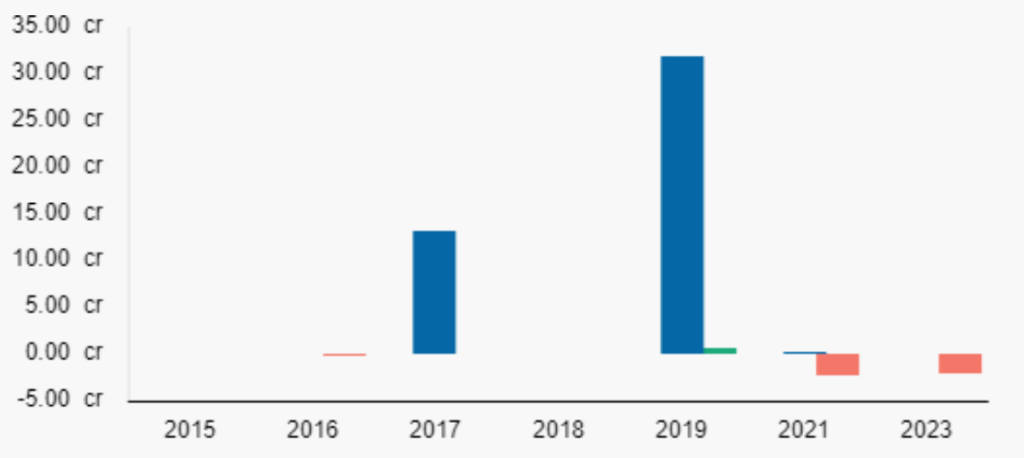

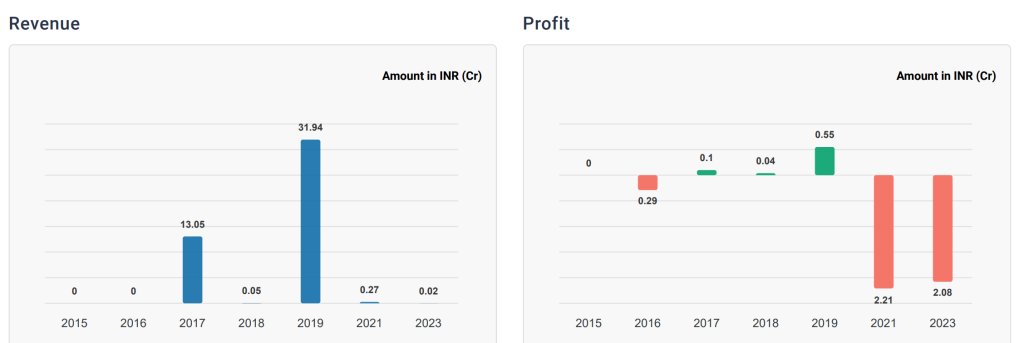

In recent years, Rosy Royal’s revenues have plummeted and its losses have mounted.

Whereas in 2019, the company recorded revenues of nearly $3.5 million, albeit with negligible profits, in the latest financial year, it recorded less than $2900 in revenues and nearly $250,000 in losses. Its bank balance was barely $30,000. Its total net worth is less than $800,000. The collapse in revenue may be due to a cancellation of some of the company’s mining leases by provincial governments in India, which the courts have reverted back for review. It is worth pointing out though that the company has a history of zero or negligible sales in some years. Its outstanding debts are about $2.1 million, out of which an amount of about $512,000 has been secured with pledged assets.

More worryingly, lenders have over $200,000 in charges against its assets still outstanding, meaning that it is unable to fully service its debts. It has a highly negative interest coverage ratio, suggesting that the amount of money it pays out in interest for loans it has taken is several multiples of its total earnings.

Both of its last two CARO-compliant audits were qualified, a sign of auditor unease. In particular, its auditors have been unable to verify the actual existence of its mining equipment, inventories, and other movable assets (it has no buildings or other immoveable property). This, clearly, is a company on the verge of full financial distress.

In any event, it is highly doubtful that the involvement of such a company as the majority shareholder of Royal Ghana will meet the high bar of LBMA certification.

It gets curioser.

In the time period corresponding to the setup of Royal Ghana Gold Limited, Rosy Royal has made no overseas investments, certainly none to the magnitude of $20 million to $25 million as the newly launched refinery is said to have cost. Nowhere does Rosy Royal disclose this massive investment outlay. It is not reflected in its assets, borrowings, or anywhere else in its books over the relevant period. In fact, there is no trace whatsoever of any investment in any kind of subsidiary, related party, or joint venture in its recent accounts. Nothing. Nada. Zilch!

Folks, we have a problem

In short, dear readers, from the information available on Rosy Royal, we are fairly confident in our analysis that it IS NOT the financial investor in Royal Ghana Gold Refinery. As if to make that point amply clear, it has not assigned any management or board personnel to the company, and it does not appear to have been involved in the actual technical setup, seeing as it doesn’t even have the expertise in refinery management.

The current chairperson of Royal Ghana is a senior ruling party politician, well known as the party boss of the Eastern Region, from where the president and key members of his administration hail. He was presumably given the role because he also chairs the board of the PMMC.

The technical brain behind the entire operation is a certain Sandeep Chadha, a consultant at Rare Tech Projects. Rare Tech is a tiny boutique general management consultancy based in New Delhi, India. It has an omnivorous appetite that has seen it get involved in representing agents in nearly every business opportunity under the sun, from textiles to health equipment.

No footprint whatsoever of any “Rosy Royal Minerals” entity can be traced through or in the setup, funding, and current operations of Royal Ghana Gold Refinery.

Which raises the fat, round, and voluptuous question: who exactly owns the 80% stake in Ghana’s “first” commercial gold refinery? For whose benefit are the impending monopolistic gold refining privileges intended?

[This is a developing story.]