Young, vibrant and bubbly, YouTuber Tiba al-Ali became a hit with her fun-loving videos about her life.

She started her channel after moving from her native Iraq to Turkey at the age of 17 in 2017, talking about her independence, her fiancé, make-up and other things. Tiba appeared happy and attracted tens of thousands of subscribers.

This January she went back to Iraq to visit her family – and was murdered by her father. However, the killing was not considered to have been “pre-meditated” and her father was sentenced to only six months in prison.

Tiba’s death sparked protests across Iraq about its laws regarding so-called “honour killings”, the case highlighting how women are treated in a country where conservative attitudes remain dominant.

‘Strangled in her sleep’

Tiba built an online following of more than 20,000 subscribers – a figure which has swelled since her death.

She posted videos daily and enjoyed the new lifestyle Turkey had opened up for her.

In her first video in November 2021, Tiba said she moved to improve her education but chose to stay because she enjoyed life there.

According to reports, her father, Tayyip Ali, did not agree with her decision to move there – nor to marry her Syrian-born fiancé, with whom she lived in Istanbul.

It is believed Tiba became involved in a family dispute when she returned to Iraq to visit her home in Diwaniya in January.

Reports say Tayyip Ali strangled her to death in her sleep on 31 January. He later turned himself in to the police.

A member of the local government where Tiba was killed said her father was sentenced in April to a short prison term.

In the wake of Tiba’s murder, hundreds of women took to the streets in Iraq to protest against legislation around “honour killings”.

The Iraqi Penal Code permits “honour” as a mitigation for crimes of violence committed against family members, according to Home Office analysis.

The Code allows for lenient punishments for “honour killings” on the grounds of provocation or if the accused had “honourable motives”.

Iraq’s interior ministry spokesman, Gen Saad Maan, told the BBC: “An accident happened to Tiba al-Ali. In the perspective of law, it is a criminal accident, and in other perspectives, it is an accident of honour killings.”

Gen Maan said Tiba and her father had a heated argument during her stay in Iraq.

He also explained that the day before her murder, police had attempted to intervene.

When asked about the response of authorities to the killing, Gen Maan said: “Security forces dealt with the case with the highest standards of professionalism and applied the law.

“They started a preliminary and judicial investigation, gathered all the evidence and referred the file to the judiciary to pass a sentence.”

‘Rooted in misogyny’

Tiba’s killing, and the lenient sentence handed to her father, sparked outrage among Iraqi women and women’s rights activists across the world about the lack of protection from domestic violence for women and girls under Iraqi law.

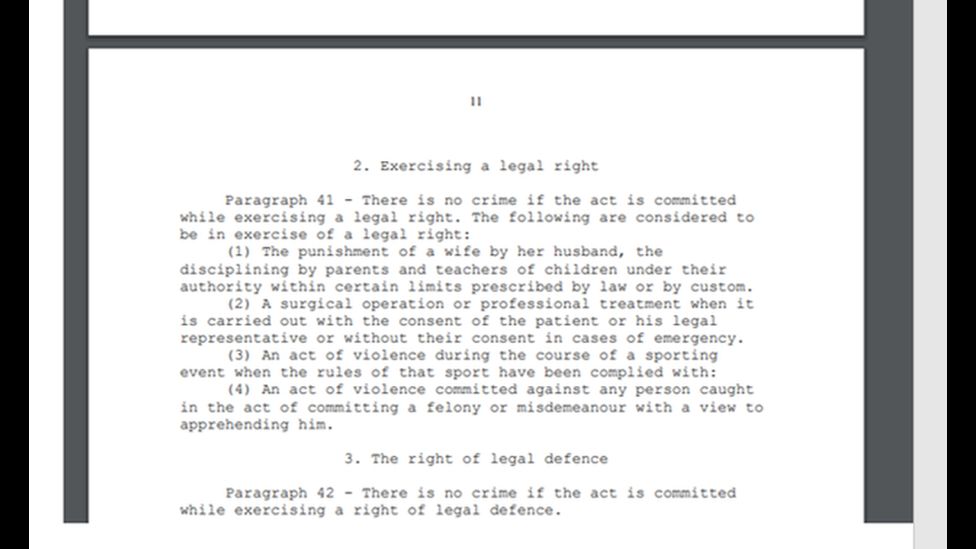

For instance, in Article 41 of Iraq’s penal code the “punishment of a wife by her husband” and “the disciplining by parents… of children under their authority within certain limits” are considered legal rights.

Article 409 meanwhile states: “Any person who surprises his wife in the act of adultery or finds his girlfriend in bed with her lover and kills them immediately or one of them, or assaults one of them so that he or she dies or is left permanently disabled, is punishable by a period of detention not exceeding three years.”

Female rights activist, Dr Leyla Hussein told the BBC: “These killings are often rooted in misogyny and a desire to control women’s bodies and behaviour.

“Using the term “honour killing” can be harmful to the victims and their families,” she said. “It reinforces the idea that they are somehow responsible for their own deaths, that they brought it upon themselves by doing something wrong or shameful.”

The UN has estimatedthat 5,000 women and girls across the world are murdered by family members each year in “honour killings”.

‘This must stop’

Five days after Tiba’s death, Iraqi security forces prevented 20 activists from demonstrating outside the Supreme Judicial Council in Baghdad.

They held placards saying “Stop killing women” and “Stop [article] 409”, and chanted: “There is no honour in the crime of killing women.”

Ruaa Khalaf, an Iraqi activist and human rights defender, said: “Iraqi law greatly needs to be improved, amended and harmonised with international conventions.”

Ms Khalaf said the sentence handed to Tiba’s father was “unfair”, and that she saw such cases as evidence of “provisions and legislations that violate women’s rights”.

Hanan Abdelkhaleq, an Iraqi advocate for women’s rights, said: “They need to find a solution. This must stop. Killing women has become too simple.

“Strangling, stabbing. It has become easy. We hope that the law will stop article 409, cancel it.”

Other female activists on social media also noted that Tiba’s killing was not an isolated incident and that many “honour killings” went unreported.

The murder has sparked conversations about tougher laws to protect women in the country and beyond.

Ala Talabani, head of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan’s bloc in the Iraqi parliament, said: “Women in our societies are hostage to backward customs due to the absence of legal deterrents and government measures, which currently are not commensurate with the size of domestic violence crimes.”

She called on fellow MPs to pass the draft Anti-Domestic Violence Law, which explicitly safeguards family members from acts of violence, including homicides and severe physical harm.

The United Nations Mission in Iraq said Tiba’s “abhorrent killing” was a “regretful reminder of the violence and injustice that still exists against women and girls in Iraq today”.

It also called on the Iraqi government to “support laws and policies to prevent violence against women and girls, take all necessary measures to address impunity by ensuring that all perpetrators of such crimes are brought to justice and the rights of women and girls are protected”.

For many, Tiba’s story has put the spotlight on outdated laws failing to protect women from harm and gender-based violence across the world.

But for others she is just another example of what is often covered up and the thousands before her who never had their story told.