A helpless anger pervades the Dalit community in the remote Indian village of Kot.

Last month, a group of upper-caste men allegedly beat up a 21-year-old Dalit resident, named Jitendra, so badly that he died nine days later.

His alleged crime: he sat on a chair and ate in their presence at a wedding.

Not even one of the hundreds of guests who attended the wedding celebration – also of a young Dalit man – will go on record to describe what happened to Jitendra on 26 April.

Afraid of a backlash, they will only admit to being at a large ground where the wedding feast was being held.

Only the police have publicly said what happened.

The wedding food had been cooked by upper-caste residents because many people in remote regions don’t touch any food prepared by Dalits, who are the bottom of the rigid Hindu caste hierarchy.

“The scuffle happened when food was being served. The controversy erupted over who was sitting on the chair,” police officer Ashok Kumar said.

The incident has been registered under the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities Act) – a law meant to protect historically oppressed communities.

Dalits, formerly known as untouchables, have suffered public shaming for generations at the hands of upper-caste Hindus.

Geeta Devi says she found her son injured outside their home

Dalits continue to face widespread atrocities across the country and any attempts at upward social mobility are violently put down.

For example, four wedding processions of Dalits were attacked in the western state of Gujarat within a week in May.

It is still common to see reports of Dalits being threatened, beaten and killed for seemingly mundane reasons.

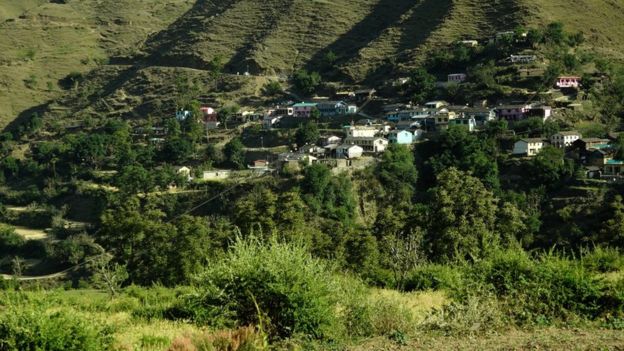

The culture that pervades their community is visible everywhere – including in Kot, which is in the hilly northern state of Uttarakhand.

Local residents from the Dalit community allege that Jitendra was beaten and humiliated at the wedding.

They say he left the event in tears, but was ambushed again a short distance away and attacked again – this time more brutally.

Jitendra’s mother, Geeta Devi, found him injured outside their dilapidated house early the next morning.

“He had been perhaps lying there the entire night,” she said, pointing to where she found him. “He had bruises and injury marks all over his body. He tried to speak but couldn’t.”

Dalits are outnumbered by upper-caste families in the village

She does not know who left her son outside their home. He died nine days later in hospital.

Jitendra’s death is a double tragedy for his mother – nearly five years ago her husband also died.

This meant that Jitendra, who was a carpenter, became the family’s only breadwinner and had to drop out of school to start working.

Family and friends describe him as a private man who spoke very little.

Loved ones have been demanding justice for his death, but have found little support among the community.

“There is fear. The family lives in a remote area. They have no land and are financially fragile,” Dalit activist Jabar Singh Verma said. “In surrounding villages too, the Dalits are outnumbered by families from higher castes.”

Of the 50 families in Jitendra’s village, only some 12 or 13 are Dalits.

Dalits comprise almost 19% of Uttarakhand’s population and the state has a history of atrocities committed against them.

Police have arrested seven men in connection with Jitendra’s death, but all of them deny any involvement.

Upper-caste villagers deny discriminating against the Dalit community

“It’s a conspiracy against our family,” said a woman whose father, uncles and brothers are among the accused. “Why would my father use caste slurs at a Dalit’s marriage?”

“He must have been embarrassed that he got beaten and popped dozens of pills that led to his death,” another local upper-caste person said.

But the Dalits in the village, who are livid over Jitendra’s death, hotly deny these claims.

They say Jitendra suffered from epilepsy, but insist there is no chance that he overdosed on his medication.

Apart from these expressions of anger, local Dalit families have largely remained silent.

“It is because they are economically dependent on families from the higher castes,” activist Daulat Kunwar said.

“Most Dalits are landless. They work the fields of their wealthy upper-caste neighbours. They know the consequences of speaking out loud.”

Jitendra’s family has already experienced some of these consequences – Geeta Devi says they are under pressure to stop pushing for the truth.

“Some men came over to our house and tried to scare us,” she said. “There is no one to support us but I will never give up our quest for justice.”

Source: BBC