The client is a 50-year-old man in the US, the attractive young white woman he is chatting with online is Gingerhoney, a model whose profile image shows her lying prone on her bed.

The client thinks Gingerhoney is nearby but he has no idea that she is actually a man far away, in Nigeria.

Men across the world, like this one, pay hundreds of dollars on adult websites to chat with what they think are attractive young women, but could in fact be anyone, the BBC has found.

Months of gathering evidence revealed a global operation which is behind these fake profiles, reaching from The Netherlands to the US, via Suriname to Nigeria, where it may be breaking strict laws on adult digital conduct.

Nigerian university student Abiodun (not his real name) is one of many people operating fake profiles on dating websites owned by Dutch firm Meteor Interactive BV.

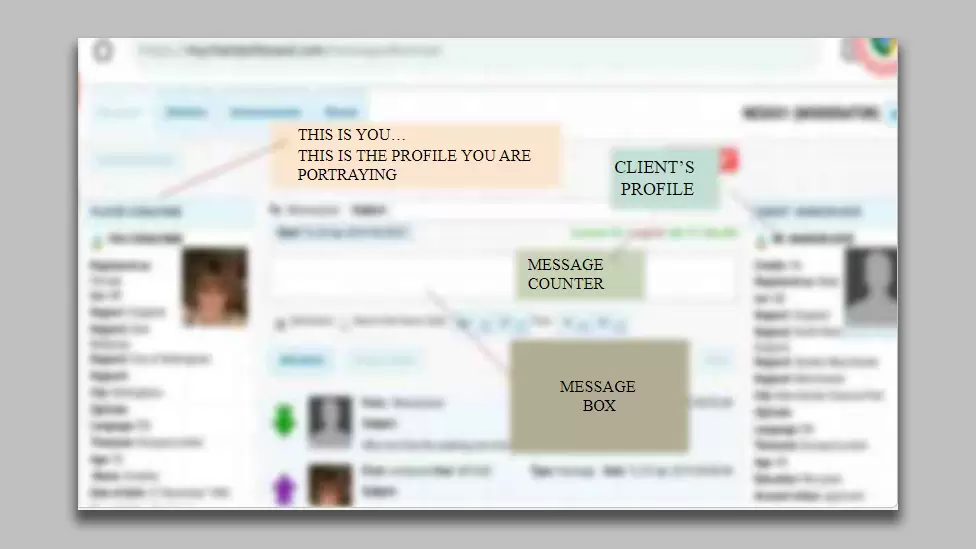

Abiodun switches profiles between the dozens of fake accounts he manages on these websites, but each time he purports to be an attractive young white woman.

On one site he is Gingerhoney, a 21-year-old model with a pink-coloured duvet draped suggestively around her waist.

She describes herself as the best thing since honey and encourages men to call her Ginger – “the same colour as my hair”.

Somewhere on Abiodun’s computer is a folder containing various lewd images of Gingerhoney, just in case a client requests more erotic pictures.

The images, including the profile picture, are stock photos taken from various sources.

Abiodun is not the only one with access to Gingerhoney’s profile – dozens of other people manage her around the clock on a shift basis.

Abiodun and his colleagues use an advanced map tool to fake Gingerhoney’s location within a 50km (30 mile)-radius of the client, which is why they were matched up. The client has paid for this chat and though he has not said it yet, he hopes to meet her.

While the websites are free to join, clients have to subscribe to packages, which cost from $6 (£5) to $300 (£255), to receive or send messages to the “women”.

While younger clients want to physically meet the women they think are in their vicinity, older clients are often satisfied with sex chats and erotic photos and videos, Abiodun says.

The aim of Abiodun and others is to keep these subscribers on the websites as long as possible with the intention of using up their credits.

They are instructed that each message must be at least 150 characters and be “open-ended”, to keep the conversation going.

“It is like a customer-service job, only the client thinks they are chatting with the CEO,” Abiodun told the BBC.

Meteor Interactive BV uses an outsourcing company in Suriname – Logical Moderation Solutions (LMS), founded by a Surinamese man called Orano Rose, to recruit, train and staff its Nigerian workers.

The BBC saw evidence on the WhatsApp, Telegram and Skype accounts of LMS which revealed that the company had recruited and trained hundreds of people, mostly in the Nigerian states of Lagos and Abuja.

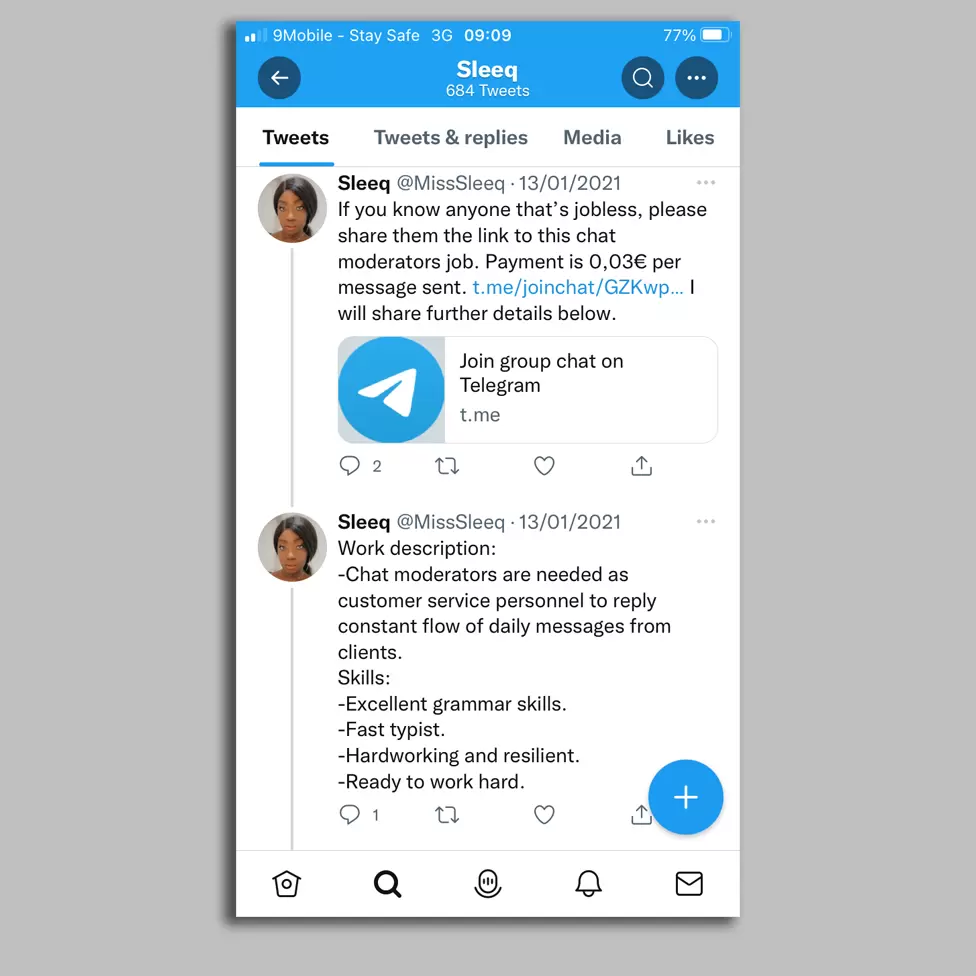

The jobs are advertised on Instagram, Twitter and Telegram, aimed at Nigeria’s army of unemployed, educated young people as “online roles”, “digital marketing jobs”, “chat moderator roles”, without any mention of the adult content employees have to deal with.

One of LMS’ top recruiters, Adedamola Yusuf, based in Germany, handles the job adverts on her social media accounts, where she shows off a lifestyle of glitz and glamour with holidays in exotic locations.

“You’re chatting with bored white people. And the job is perfectly legal and licensed both in Germany and Nigeria,” she said on a WhatsApp chat with potential hires on their first day.

Ms Yusuf has been recruiting people for more than two years and in one recruitment drive last November, hundreds of people signed up.

She did not respond to BBC requests for comment.

“These guys from the West majorly want to have a chat,” one trainer told new recruits, who have to pass strenuous English language tests to make their cover as fool-proof as possible.

“It is: ‘I am’, not ‘am’,” one recruit was corrected during a training session in the company’s WhatsApp group that I attended.

Nicholas Akande, a director with LMS in Nigeria, registered more than 100 people in the first week of July and told them the job was legal.

He did not respond to BBC requests for comment.

The recruits are also given lessons about the culture, writing style and trending conversations in the locations of their clients to make them sound authentic.

At the end of training that can last from a few days to a week, they are given log-in details on the websites, where they can see personal information such as the home address, phone number and age of subscribers.

The BBC has seen comments from men online, who said they spent from $300 to $700 on these websites hoping to meet the “women” they were chatting with.

“I must have texted 20 women and was always put off when it was suggested to meet personally,” said one man, who claimed he had spent $64.99 on a site owned by Meteor Interactive.

Another man said he had “bought over $400 of credits with the understanding that the women were real… my bad at not reading the fine print”, he said.

One man said he had spent more than $300 on credits on the false hope of meeting the women in person:

“They hook you saying they live in your town or close by and want to meet you “TONIGHT” you spend credits texting them and when you want to set a place and time to meet then the excuses start,” he said.

Meteor Interactive says its Terms & Conditions makes it clear that some of its profiles are fictional and that “the possibility of a meet-up are not possible”.

However, it does not explain why its Nigerian workers use the map tool to fake their location.

This tool gives the deception more credibility and raises false hopes of a meeting which never happens.

The activities of these people border on internet fraud in Nigeria under a law that prohibits posting obscene or adult content online, experts told the BBC.

A 2015 cybercrimes law prohibits:

- sending electronic messages that materially misrepresents facts

- sending messages that are grossly offensive, pornographic, indecent, obscene or menacing

- using a financial card to fraudulently obtain services.

One government official said LMS risked being deregistered in Nigeria if it was involved in deception and adult content.

Mr Rose told the BBC that he was doing nothing illegal, and was not aware of the cybercrimes law in Nigeria. As he is based in Suriname, it would be difficult to prosecute him.

Millions of Nigerians are unemployed and a months-long strike by university lecturers means many young people are desperately looking for jobs.

LMS woos recruits with monthly salaries of up to 150,000 naira (£300, $355) – twice as much as new teachers – which they can make by sending a minimum of 500 messages per day to different clients.

Abiodun considers his role “a small piece of a global operation and a lesser crime when compared to internet fraud”.

“It’s no different from chatting with a loved one or a friend, which millions of people do every day,” he says, switching to Gingerhoney as a message pops up on the dashboard.

It is the 50-year-old man in the US, asking for a meeting.

“Oh sorry, I have to walk my dog now,” Gingerhoney responds.

It is the sort of excuse that he has been trained to use to deflect such requests.

Abiodun closes the tab and opens another where Erikka, “a pearl who can satisfy your craziest fantasies”, has a message waiting for her from Sam in London.