Twenty years ago the man who recorded one of the most successful songs of all time was thrown off a motorbike by a car in Calabar, Nigeria.

He hit his head on the road and was rushed to the hospital, where he lay for two weeks, in and out of consciousness, but deteriorating all the time. On June 24, 1997, Prince Nico Mbarga was pronounced dead.

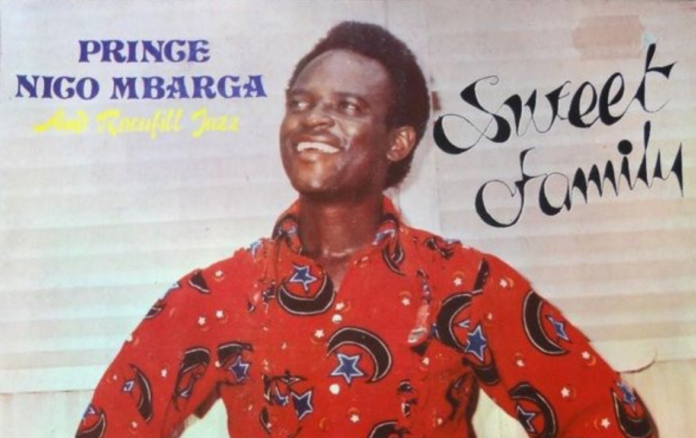

“Sweet Mother,” his 1976 one-hit wonder, had sold at least 13 million copies across the African continent – more than The Beatles’ bestseller “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” But no global media outlet thought to cover the life and death of the artist behind Africa’s most popular song.

Today, the only internet accounts of his life reach around four paragraphs and bookend Mbarga’s career with two big political events of the time: the Biafran War in 1967 that saw him, at 17, flee across the border to Cameroon, where he mastered the guitar; and the expulsion of undocumented migrants from Nigeria in 1983, with his band’s Cameroonian members among the two million West Africans forced to leave the country.

Politics, however, rarely frames lives quite so neatly.

Over the last few months, I have tried to piece together a more textured story: traveling to Mbarga’s hometown to talk to his childhood friend, his wife and his mistress; tracking down his former band members from Cameroon to France to the US; prodding the memory of his octogenarian producer; and reading rare transcripts of his interviews.

Twenty years after his death, this is the obituary that never was.

The first place Mbarga knew, the town of Ikom was the last stop on my journey. In a modest bungalow there I met Esame, his widow, and Ojong, his best friend, on a warm evening on the cusp of the wet season. On plastic chairs in the shadow of his mausoleum, they told me about Nico Mbarga and the place he called home.

The son of a Cameroonian father and a Nigerian mother, Nico Mbarga was born in nearby Abakaliki on April 8, 1950, but grew up in Ikom.

In the 1950s it was little more than a series of administrative buildings, houses and farms clumped around Cross River, surrounded by tropical rainforest, right on Nigeria’s eastern border with Cameroon.

Ojong remembers early mornings with young Nico on the river, fishing for tilapia and catfish, and days spent in the shade of the forests, setting traps for birds.

Today Ikom is still fairly remote – the tarmac roads coming in and out quickly crumble into dirt – but back then it was positively isolated. The only way goods such as bicycles and sewing machines made their way to the village was by lighters on the river from Calabar, more than 100 miles to the south.

But even in rural Ikom, all the flux of being in a British colony in Africa in the mid-twentieth century – and the trappings of modernity it entailed – had its effect.

Nico’s father drew a salary sawing timber, so Nico himself was able to go to primary school (perhaps fewer than one in five children did at the time).

More exciting for Nico though, his music-loving father bought a Phillips radio. For if anything was to capture the mood of the new country emerging in Nigeria’s faraway and growing cities, it was the highlife music he could now hear from home.

From Bobby Benson’s “Taxi Driver,” to EC Arinze’s “Saturday Night,” to Rex Lawson’s “Yellow Sisi,” highlife was a music of young men in big towns, marveling at cars, dancing at nightclubs, chasing single women.

There was something, a new confidence, beyond the lyrics too. From miners’ football clubs in the Zambian Copperbelt to the newspapers of the intelligentsia on Ghana’s coast, Africans were making colonial tools their own.

Highlife took western instruments – the trumpets and saxophones of big jazz bands – and set them to local, offbeat rhythms.

It was a genre well-suited to a country preparing for independence, and its optimistic sound was to suffuse all the music young Nico would go on to create. (Even his later song “Oh Death,” with the opening line “Oh death, everybody hates you,” is impossibly cheery.)

His father, from a long line of xylophone players, taught him the instrument, a handheld version with metal tines plucked by the thumbs.

But Nico wanted to make a sound more like the western instruments of highlife, so he built his own xylophone from dried-out plantain skins and scooped bark. “It was completely something that he innovated,” Ojong recalls.

Despite the celebratory mood of the country, however, Nico’s childhood was not easy. His father died of a sudden illness, and the family he left behind – his wife, three sons and a daughter – became reliant on Nico’s mother, a peasant farmer.

They downsized, becoming tenants in a compound in the middle of the village, and though Ojong remembers a mother dearly trying her best – caregiver with one hand, breadwinner the other – things were difficult.

As a teenager, Nico tried to do his bit, playing sets in nearby small villages, but there was little money in it.

Thus when the Biafran War broke out in 1967, Nico Mbarga wasn’t so much fleeing for his safety – the rest of his family stayed in Ikom – as pursuing his ambitions in music.

The civil war put a sharp stop to eastern Nigeria’s vibrant music scene, but the hotel gig economy was still running over the border.

In Mamfe, Cameroon, he met Lucy, who today lives in a half-built mansion ringed by palm trees on the outskirts of Ikom. I had been slightly nervous about meeting Lucy myself, remembering my first call back in London with Esame, Mbarga’s wife: “And I’ve been told about someone called Lucy as well, who is that?”

“Oh that is his concubine,” she responded matter-of-factly, “I will take you to her.” My worries were eased by their laughing and hugging as they greeted each other. Then a smiling Lucy recounted the moment 50 years ago when she met Nico Mbarga: a charming, handsome, if slightly short and dirt-poor 17-year-old.

“As I first see him, I love him, eh? Even my mother did no gree, she said, ‘He’s a small boy, he don’t have money,’ but I said, ‘No, that boy is my choice.’”

Indeed, despite the objections of her parents, and their own struggles to buy even “a money for pot” to boil water, she would soon have the first of her two children with Mbarga.

Working as a “band boy” for a Congolese cover group in Mamfe, carrying instruments for concerts at hotels in nearby towns, Mbarga came to learn and love Congolese rumba.

With its staccato guitar, spontaneous spoken asides and high-pitched harmonies, it had the whole continent dancing the soukous and the kara-kara. Mbarga, always dedicated, taught himself the conga, the drums, the bass and, most importantly, the finger-picking style of Congolese electric guitar.

When the three hard years of the Biafran War came to an end, he looked to launch his career back in Nigeria.

After one failed border-crossing by road, in which Lucy and Mbarga were arrested by officials and sent to prison for three days for not having passports, they successfully made it across a second time, going “the bush way” in 1970.

They came to Onitsha, a trading town on the banks of the Niger River, with at its center one of the largest markets on the continent. And while the money this brought has always attracted writers and musicians – today there are shops stacked high with thousands of albums in paper covers, posters for studio rentals everywhere, and music filling the air – the 1970s was Onitsha’s heyday, fuelled by Nigeria’s petrol boom and the good mood of people just relieved to get on with their lives again.

It was, as Chinua Achebe wrote, “the esoteric region from which creativity sallies forth at will to manifest itself,” and the home of some of Nigeria’s great highlife musicians.

“We loved the place,” Lucy almost shouts. “From there, God blessed him.”

Mbarga thrived. He formed his group, Rocafil Jazz, signed a contract to play every Sunday at Onitsha’s Plaza Hotel, and began to mix with stars like Stephen Osadebe and Bobby Benson.

Then, in 1973 he was picked up by EMI and recorded his first hit “I No Go Marry My Papa,” about a daughter disagreeing with her parents over the choice of her husband, surely inspired by Mbarga’s brush with Lucy’s parents. It sold reasonably well – “I did not know that I would make such an amount in my life,” Mbarga said of the modest success – and in it you can hear the beginnings of something, a mix of influences, that would come to define his music.

Odion Iruoje, then a producer at EMI, recalls working with a 23-year-old Mbarga “who knew what he wanted,” very able at “directing his boys.” By all accounts the non-smoking, non-drinking Mbarga, who studied law on the side in Onitsha, was a man of real self-possession.

He was not to be deterred, therefore, by the stalling of his career after his first single. Mbarga was dropped by EMI for failing to create any other commercial hits. Instead, around 1974, tired of “I love you, you love me, my baby,” he wrote “Sweet Mother.”

It was a love song from a son to a mother that, in its old-fashioned way, never actually once says “I love you.” Instead, it’s a grateful son praising what his mother did for him as a child: drying his tears, putting him to bed, feeding him, praying when he’s ill:

When I dey hungry my mother go run up and down / she dey find me something when I go chop oh! / Sweet Mother a-aah / Sweet Mother oh-e-oh!

And if “Sweet Mother” was dedicated to all mothers and the things they do for children, it was inspired by the loving sacrifices Mbarga saw his own mother, a widowed farmer, make after his father died. The lyrics began, “Sweet Mother, I no go forget you, for dey suffer wey you suffer for me.”

Mbarga sent a tape to Odion Iruoje at EMI, who remembers hearing the song for the first time and knowing that “it was the magic.” On the agreed date for recording, however, Odion had to fly to London to record at Abbey Road, and some other EMI officials told Mbarga that the song was “too childish” for them to record.

Affronted, Mbarga did not come back. So it was only two years later when the small, Onitsha-based producer Rogers All Stars heard “Sweet Mother” at the Plaza Hotel, that the song found a label to release it.

Rogers All Stars is now in his 80s, slightly frail and very soft-spoken, still working in his Onitsha studio with which he now shares his name. And though his memories sometimes come to him in a slight haze, he still clearly recalls the day Nico Mbarga came to the producer’s house uninvited early one morning to introduce himself. They bonded over Rogers’s collection of Congolese records, and Mbarga invited the older man to come see him one day at the hotel. “I could see he was a star,” Rogers says.

For six months Mbarga – now calling himself Prince Nico Mbarga – Rocafil and Rogers All Stars worked on “Sweet Mother,” rehearsing daily from seven in the morning until one in the afternoon. It was, says Rocafil rhythm guitarist, Cameroonian Jean Duclair, “real every day work,” as they made change after change, turning it from a gentle “cha cha cha” to a more upbeat highlife sound, adding little dance breaks, and crafting a song marked more and more by the drive of Mbarga’s Congolese-style finger-picking lead guitar.

Finally satisfied, the band travelled across the country to record, and after a heavy night in a Lagos hotel, with all but Mbarga drinking and smoking, recorded it live at Decca Studios – hung over for sure, but they had practiced so much it hardly mattered.

It took a few months to really take off. Nigerian radio host Benson Idonije rates the fact that it eventually did as one of his finest achievements. At the time, he explains from his house in Lagos, he had just launched Radio Nigeria Two, the country’s FM station. After shows he would often drop into bars to wind down the night.

On one of these evenings in late ’77, he remembers, there was a song released by an obscure label from Onitsha, that got everyone up to dance. With an inkling that his audience might like the song’s message, he found it, undiscovered, in Radio Nigeria’s gramophone library, and played it that evening. “I started getting calls from everywhere,” he says. From then on, for months nearly every request Radio Nigeria received was for “Sweet Mother.”

“You have hit jackpot,” Jean Duclair remembers being told by their producer, with the record suddenly selling out in the shops. On a 20-seater Mercedes bus bought by Rogers, Mbarga and his band toured the country, up north during the wet season, down south when the rains stopped.

And though culturally Nigeria can be a divided place, Jean remembers Nigerians everywhere demanding “Sweet Mother” – “it was like a national anthem.”

Soon they were touring all across West Africa – Togo, Cameroon, Cote D’Ivoire, Ghana, Benin and Burkina Faso – and even as far east as Kenya. As Jean Duclair recalls, the band members were scared to leave the plane when they saw the crowds waiting for them at airports, wearing Rocafil Jazz t-shirts, screaming Mbarga’s name.

And what was the reason for its success? Certainly, with its Congolese guitar-picking, its West African highlife beat and its pidgin lyrics, “Sweet Mother” had something for people all over.

Yet even beyond that, perhaps what it really caught was differing shades of Africa at the time. For, by the 1970s, these were societies that – after the profound changes wrought first by colonialism, then by the liberation movements that challenged it, and finally by the mixed records of those same movements once in power – had reason to feel both excited and uneasy at the new continent these encounters had created.

It was a creative tension at the heart of “Sweet Mother.” In its style, with its hybrid English and its electric guitars calling its listeners to dance, it was unquestionably modern; but in its content, with its heartfelt praise for the nurturing role of mothers, “Sweet Mother” nodded to a more traditional life. It was a contradiction that Mbarga embodied himself. He was a man who would later, in “Green Revolution,” bemoan the flight of the sons and daughters of the land for the lure of the city – singing, “let’s go farming, and be self-sufficient!” – while he himself performed on stage in Nigeria’s biggest towns in his famous three-inch platform shoes. As his best friend Ojong would say, “He’s a blender.”

Or perhaps it was just a great tune.

Regardless, Mbarga and Rocafil Jazz were completely unprepared for the popularity of “Sweet Mother.” While numerous online reports of Mbarga’s career have Rocafil Jazz falling apart when, in 1983, Nigeria’s President Shagari ordered the country’s two million undocumented migrants to leave – amongst them Rocafil’s Cameroonian musicians – no former band member I spoke with recognized that story. Instead, it was something much more mundane: money. On its release, they were a local band that practiced in a small compound in Onitsha, playing Sunday gigs at the Plaza Hotel with instruments that Rogers All Stars himself had bought for them, and with no contracts in place. It was always an issue with the potential to cause problems. After a loss-making and slightly demoralizing tour to London in ’79 – playing at venues like St. Pancras Town Hall and the African Centre to half-empty European crowds – the members of Rocafil Jazz complained to Mbarga that they were underpaid.

Mbarga was, according to Jean Duclair, unwilling to give an inch, and the mood soured. Before a scheduled trip to Japan, unable to agree on their percentages, Rocafil disbanded. Though they later re-formed, changed members, re-formed and disbanded again, the band never quite gained the same momentum – there was even an actual physical altercation, broken up by the police, after a New Year’s Eve hotel show in 1980.

Meanwhile, convinced that Rogers All Stars hadn’t given him his share of the royalties, Mbarga unsuccessfully took his producer to court. (Everyone did eventually reconcile – Rogers refers to Mbarga as “like a son.”)

In the end, not much of the money made from “Sweet Mother” ever made it back to any of them. Royalty payments were limited by the hundreds of pirate recordings of the song, as economies across the continent began to suffer and record stores started to make their money by dubbing cassettes.

No one involved with “Sweet Mother” is now living a life that would suggest they were behind one of the top twenty bestselling songs in history. Mbarga’s family live in a pleasant but modest bungalow in Ikom; his former band members like Jean Duclair still struggle to raise funds for their musical projects; and his old producer, Rogers All Stars, though he owns a four-story building in Onitsha, admitted to many mistakes in trying to protect “Sweet Mother” from piracy.

“You can see,” he says in his dusty office, exaggerating slightly in a room that still dwarfs his fragile frame, “you can see how poor we are.”

With the money he did receive from “Sweet Mother,” Mbarga moved back to Ikom, built and managed the Sweet Mother Hotel – where he would perform every Sunday – and married a local girl, Esame, the daughter of the owner of the only petrol station in town. He also built the house where she still lives today.

Lucy and their two children also moved to Ikom. Indeed, while Mbarga eulogized about mothers on stage, he did not quite show so much respect to the mothers of his own children. “His only weakness was temptation,” says Rogers. For alongside Esame, his wife, and Lucy, his first love, he had numerous other lovers. Even a track on his first album,

“Christiana,” two songs after “Sweet Mother,” is about a girl he was courting in Onitsha. It was an attitude he alluded to in “Sweet Mother” itself, asking before one of its many instrumental breaks: “You fit get another wife / you fit get another husband / but you fit get another mother? No!” Not that, when pressed on it all these years later, neither Lucy nor Esame seem to mind that much.

And if Mbarga disappeared from the music scene, it was not through lack of trying. Esame recalls that he would sing, play air guitar and compose songs even when they were eating. He would go on to produce 17 albums and records after “Sweet Mother,” all with the same highlife beat and Congolese style guitar. In fact, he didn’t even rate “Sweet Mother” as one of his best songs, preferring “Simplicity” instead.

But while the lives of some artists darken as the fame fades, there is no such twist here. Mbarga lived a satisfied life, caring for his own mother, supporting his two “wives” and spoiling his children with gifts. He was, on the accounts of both Lucy and Esame, a loving father, “too sweet” to punish his kids, always willing to dance with them. “He lived a happy life,” Esame says.

It was Mbarga’s desire to carry on his music that saw his end in Calabar 20 years ago. If his childhood witnessed the enthusiasm of early independence, his death seemed a cruel symbol of what the impoverished Nigeria of the 1990s had become. After a ten-year hiatus, the original band was back together for a 50-state tour of the U.S. and Mbarga was on his way to pick up visas. His car ran out of fuel – a scandalously common occurrence in one of the world’s largest oil exporters – so he hopped on an okada (motorbike taxi) to complete the journey and, once in Calabar, was thrown off by a car.

In the hospital for two weeks, visited by his band members, his friends, his children and his first love Lucy – who held his hand as he drifted in and out of consciousness – he died with Esame at his side. Back home in Ikom, his elderly mother fell down when she heard the news, and did not get back up. She died too shortly afterwards.

It was a fitting end for the two of them. Mbarga never forgot all that his mother did for him when he was a boy – leaving their home every day before dawn to work on a rented plot, growing bananas and yams, trying to raise four children – and he spent his life paying her back for it. She was, by all accounts, delighted with “Sweet Mother,” his timeless dedication to her.

When Rocafil Jazz were in Onitsha, she would come down every month to watch them practice, dancing with a broom in her hand, and inviting them all back to Ikom so she could feed them up. As she aged, he took care of her, as Lucy remembers, refusing to eat until she had, and talking to her morning and night. After all, he did say in his bestseller, “If you forget your mother, you’ve lost your life.”

As I traveled throughout Nigeria, I noticed Nico Mbarga moving from a human being who had lived here on earth to, on a small scale, an icon in the making. The things he touched and made in life were slowly fading away: the Ikom compound where he grew up with his mother had been knocked down, leaving just an empty plot; the multitrack records of his “Sweet Mother” studio session in Lagos had long been thrown away; his Sweet Mother hotel, under different ownership now, was completely rundown.

In their place, in Ikom, Mbarga is newly remembered by a statue erected early this year. It’s a golden Mbarga in his platform shoes, standing his guitar on a plinth, looking out over the traffic of “Mbarga Junction.” Nearby, shaded by Ikom’s many red-blossomed African tulip trees, is Sweet Mother Road. And if it is sad in a sense – Lucy cried the day the statue was put up, as if it were final confirmation of his death – it does at least constitute a well-earned recognition for Mbarga at last.

Which leaves just one final question: Why have Mbarga and “Sweet Mother” been so ignored elsewhere? While the continent’s cultural contributions are generally marginalized, some African music does make it outside, from Fela Kuti’s afrobeats, to Ali Farka Toure’s Malian blues, to Ethiopia’s otherworldly-sounding jazz. The music that makes it to western ears is usually tough and cool, if not explicitly political, reflective of what many perceive must be a dark political mood.

Yet none of this music, brilliant and rich as it is, has proved as popular with Africans themselves as Prince Nico Mbarga and Rocafil Jazz’s ten-minute ode to mothers. It is played at weddings, as newlywed brides about to leave their homes for the first time dance with their mums to say thank you, at birthday parties celebrating the long lives of family grandmothers, and at Mother’s Day church services, the only secular song amongst the hymns, with worshippers swinging in the aisles adding their own “hallelujah!” to Mbarga’s lyrics. The “Sweet Mother” ideal, the all-consuming mother, not eating until her children are fed, not sleeping until they sleep, crying when they are sick, might be a little conservative, but it has deep cultural roots.

The Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe wrote that discovering the jubilance of Congolese rumba in the 1980s – a time of impoverishment, of brutal wars, of cruel leaders – taught him to look beyond the mere facts of political life. In Africa, he argued, “music has always been a celebration of the ineradicability of life.” More than anything, it was the genre that articulated “the practice of joy before death.” In the west perhaps, we have only wanted to hear music from the continent about the facts; in its joyful way, “Sweet Mother” captured something else: the suffering, the love, the human relationships between those facts.

Maybe we should listen harder.

MORE: