He eventually made it to Germany, but only after surviving months of torture and starvation at the hands of three separate slave traders who bought and sold migrants as if they were cattle.

Here, he tells Bekele Atoma from the BBC’s Afaan Oromo service his remarkable story.

Harun, 27, was born in Agarfa, in the province of Bale, some 240 miles (390km) south-east of the capital Addis Adaba.

Bale has some of the highest rates of emigration in Ethiopia and, in 2013, he joined the exodus, pushed by a lack of jobs at home.

First, he travelled to Sudan, before deciding to set out on the next part of his journey to Europe.

“After living a year and a few months in Sudan, I started a journey to Libya with other migrants – paying $600 each to smugglers,” he explained.

“We were 98 on a lorry. People had to sit on top of each other and the heat was unbearable.

“We had encountered a lot of problems on our way. There are these armed people in the desert who stop you all of a sudden and steal everything you have.”

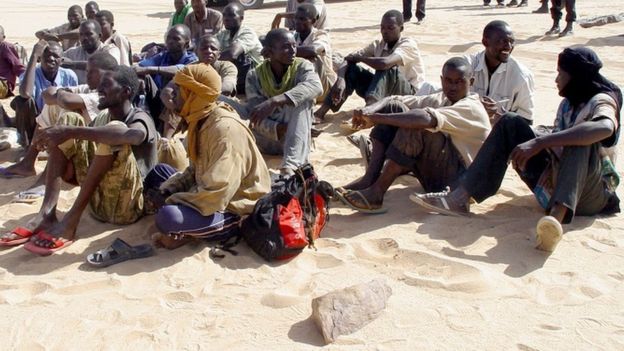

Image copyrightAFPImage captionSmugglers take people vast distances across the Sahara – for the right price

Image copyrightAFPImage captionSmugglers take people vast distances across the Sahara – for the right price

His real troubles began at the border. After six days travelling through the Sahara Desert, the group reached the border of Egypt, Libya and Chad.

It was here the smugglers met to exchange migrants, Harun said. But something went wrong.

“At the border place, a group of gangsters kidnapped us all and took us to Chad,” he said. “They drove us for two days through the Sahara and led us into their camp.”

Once there, the heavily armed group – who spoke Arabic and a number of other languages – explained what they wanted.

“They brought a car and said those of us who can pay $4,000 each can get into the car and those who can’t have to remain there.

“We didn’t have that money but we talked to each other and decided to pretend we had and to get into the car anyway.”

Image captionUnlucky groups will find themselves in the hands of slave traders

Image captionUnlucky groups will find themselves in the hands of slave traders

Harun and his friends were driven for another three days, before arriving at another place where they sell migrants – including Harun.

“Those who took us over told us that they had bought us for $4,000 each – and that unless we paid that money back we wouldn’t be going anywhere,” he said.

Their fate if they did not come up with the money was hauntingly clear.

“There were migrants, mostly of Somali and Eritrean origin, who had been there for more than five months. They had suffered a lot and they didn’t look like human beings.

“We suffered a lot too. They forced us to drink hot water mixed with petroleum to make us pay them quickly. They gave us a tiny amount of food, and only once a day. They tortured us every night.”

‘Too bony to buy’

Harun was unable to get the money to pay his new captors, and he remained trapped in the camp with another 31 Ethiopians for 80 days.

Eventually, the traders became fed up.

“‘You are not going to pay us, so we will sell you,’ the traders told us,” Harun recalled.

“We had no food for more than two months and we were very bony. As a result the man who they brought to sell us to refused to buy us, saying: ‘They don’t even have a kidney’.”

Finally, the traders found a buyer, a man from the Libyan city of Saba, who paid $3,000 each.

Image captionHarun’s route from home, to Italy

Image captionHarun’s route from home, to Italy

“We get into his car convinced we couldn’t see anything worse than we’d already seen. But in Saba, after four days of travel, we faced a suffering that was inhuman.

“They tortured us, putting plastic bags on our faces, tying our hands behind our backs, and throwing us upside down into a barrel full of water. They beat us with steel wires.”

Harun and his friends endured this torture for a month before finally managing to reach their relatives and beg them to send the money.

“They let us go but before we had got very far, some other people ambushed us and took us to their warehouse. They told us that unless we pay $1,000 each they wouldn’t let us go.

Image copyrightAFPImage captionIf they make it to Libya, the migrants still have to risk crossing the Mediterranean

Image copyrightAFPImage captionIf they make it to Libya, the migrants still have to risk crossing the Mediterranean

“The torture and beating continued. We called our families back home and asked them to send us money again. They sold their cattle, land and whatever possessions they had and sent us the money.”

Refugee status

Finally, Harun made it 480 miles north to the capital Tripoli, a major hub for those wanting to risk the dangerous journey across the Mediterranean.

“The situation there was a bit better,” Harun said. “We worked for a few months, whatever jobs we could get, and then crossed the Mediterranean to Europe.”

But even that is not safe.

“Unless you are lucky, the police will catch you and take you to prison. And they will sell you to smugglers – sometimes for as little as $500.”

Harun was one of the lucky ones: he reached Italy, before crossing into Germany – where his refugee request was accepted.

Image copyrightHARUN AHMEDImage captionHarun is now safe in Europe – but says he never would have made the journey if he had know what lay ahead

Image copyrightHARUN AHMEDImage captionHarun is now safe in Europe – but says he never would have made the journey if he had know what lay ahead

“Life is good now,” he says, but what he endured to reach Europe – and those he lost along the way – will forever remain etched on his memory.

“We buried one of our friends at the border between Egypt and Libya. Two more of them left us in the city of Saba; I don’t whether they are alive or not. Another girl fell into the Mediterranean but some others managed to reach Europe.”

But would he make the journey again, knowing what he knows now? “No,” he says.

“Frankly speaking, I lacked nothing but knowledge when I left my country. I could have gone to school or worked there.

“I saw people leaving and this, in addition the political situation, persuaded me to flee.”