The bubbly 15-year-old dreamed of becoming a firefighter, a lawyer, or veterinarian. She was passionate about drawing and spending time outside with her dogs in her small town of Bedford, Pennsylvania, about 100 miles east of Pittsburgh.

Sadie had overcome challenges before — her biological mom, a drug addict, abandoned her when she was little — but in her final year of life, the high school freshman’s biggest obstacle was bullying from her peers.

“The kids started making fun of her for her red hair and braces,” said Sarah Smith, the aunt whom Sadie lived with. “The kids told her only devils had red hair.”

The taunting started in the school hallways but became inescapable, Smith said. Sadie was tormented on Facebook, Instagram, messaging platform Kik — where classmates would tell her to kill herself.

“I went to the police. I went to the school. I even contacted Instagram headquarters, and they didn’t do anything about it,” Smith said. “So finally I smashed her phone. I broke it in half. She was bawling every day and I couldn’t take it anymore.”

But the bullying had already taken its toll. On June 19, barely a week after Smith took her phone, Sadie hanged herself.

In the age of what some are calling the “screenager” — with teens averaging more than 6.5 hours of screen time every day, according to nonprofit Common Sense Media — suicide prevention experts are wondering if enough is being done to protect young minds online.

Recent studies have shown a rise in both teen suicides and self-harm, particularly among teenage girls Sadie’s age.

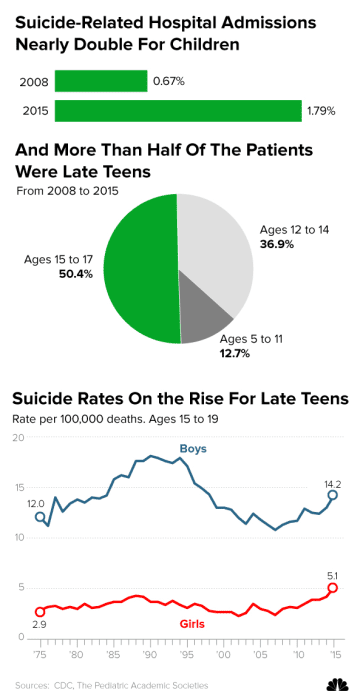

An analysis by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in August found the suicide rate among teenage girls ages 15 to 19 hit a 40-year high in 2015. Between 2007 and 2015, the rates doubled among girls and rose by more than 30 percent among teen boys.

And just this past week, researchers in the U.K. published similar discoveries in a study on self-harm that showed a dramatic increase in the number of adolescent girls who engage in it: Self-harm rose 68 percent in girls ages 13 to 16 from 2011 to 2014, with girls more common to report self-harm than boys (37.4 per 10,000 girls vs. 12.3 per 10,000 boys).

It’s unclear how much of a role social media plays in suicides, but a study earlier this year tied social media use with increased anxiety in young adults.

Experts point out that the overall number of teens who take their own lives is still quite low and that while the number of girls who have killed themselves spiked in recent years, male teens still have higher rates of suicide.

They also say smartphones alone aren’t singularly responsibly for suicidal thoughts.

“The increases in suicide rates are unlikely to be due to any single factor,” said Dr. Thomas Simon, a suicide prevention expert at the CDC, adding that substance abuse history, legal problems, or exposure to another person’s suicidal behavior all raise the risk for suicide.

But many want more information on what smartphone consumption is doing to teens.

In an article last month in The Atlantic, “Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation?”, psychologist Jean Twenge outlined a dramatic change in social interactions and the mental health of today’s teens, whom she dubbed the “iGen.”

“It’s not an exaggeration to describe iGen as being on the brink of the worst mental-health crisis in decades. Much of this deterioration can be traced to their phones,” Twenge wrote.

Filmmaker Dr. Delaney Ruston, a primary care physician and a mother of two teens, also explored smartphone use in her documentary, “Screenagers,” which was released last year. Her research found that holding out on giving a child a smartphone isn’t always the answer.

“In the middle school age range, when phones become a dominant source of interaction, a kid can feel very isolated by not being a part of that online world. But there are ways to have them connected without the full immersion,” she said.

Ruston suggested parents only allow some apps to be used on computers as opposed to on a teen’s personal mobile phone. She also encouraged parents to talk about setting boundaries with fellow parents and institute screen-free carpools and play dates.

“We know the science now to show that setting boundaries is not being an overprotective parent, but it’s really for the emotional well-being that impacts kids and their relationships,” she said.

Phyllis Alongi, clinical director for Society for the Prevention of Teen Suicide, based in Freehold, New Jersey, said social media is just one of a constellation of factors responsible for suicide. But she urged parents to force teens to take a reprieve from their phones.

“They can’t turn it off, nor do they want to or know how to,” she said. “It’s stunting their coping skills, their communication skills.”

Dr. Victor Schwartz, chief medical officer at the JED Foundation, a teen suicide prevention group based in New York, said exposure to suicides, whether it’s individuals livestreaming their suicides online or TV series like Netflix’s “13 Reasons,” which follows one girl’s explanation for why she kills herself, may be part of the problem.

“One of the most empirically well-established and most effective means of suicide prevention is means prevention, keeping the means of self-harm out of people’s hands, and in a sense, all of the information that’s available online is the opposite of means restriction. It’s means promotion in a way,” he said.

Social media can be positive in that it offers ways to be in touch and provide support for one another, Schwartz said.

But, he added, the virtual world can turn ugly — fast.

“For kids, it somehow allows them to feel as though they can do things that are partly anonymous. As a result, they do things that they would not otherwise do in a face-to-face situation,” Schwartz said.

“The second piece is the magnifying effect. Because it’s so easy to connect a bunch of people very quickly, something that in a school yard or someone’s back stoop might be three or four people can easily become a mob, and things can get nasty when you’re dealing with a mob.”

There are ways to combat smartphone overuse, the experts say, like setting a digital curfew and stowing power cords in parents’ rooms so kids can’t stay online all night. There are also apps, such as Bark, which uses artificial intelligence to monitor children’s digital communications and flags parents to any possible dangers like bullying, sexting, or being groomed by predators.

Ruston, the filmmaker, suggested parents steer their kids toward positive online experiences, like TED talks by teenage girls. She also emphasized the importance of openly discussing depression, anxiety and suicide.

“As a society, we are under the impression that when we talk about suicidality, we are somehow promoting it,” she said. “Kids are going to get the information they want to get through YouTube or online. We need to become more proactive.”

If you or anyone you know is feeling suicidal, you can call the National Suicide Prevention Hotline 24 hours a day at 1-800-273-8255; or contact Crisis Text Line, a confidential service for those wanting to text with a crisis counselor, by texting HOME to 741741.