The first time Rob Decker visited a national park, he was 6.

Yosemite National Park, with its towering sequoias, crystalline lakes and rugged Sierra Nevada mountains, already held both historical and personal significance for Decker: His grandparents had honeymooned there 40 years earlier.

The trip was the beginning of what would become a lifelong passion for the parks, one that — as a photographer and graphic artist — would ultimately inform some of his most important work.

In the USA, the national parks have drawn record crowds in recent years. More than 330 million visitors visited National Park Service sites in 2016 and 2017, and as the busy season kicks off this summer, those numbers should hold strong.

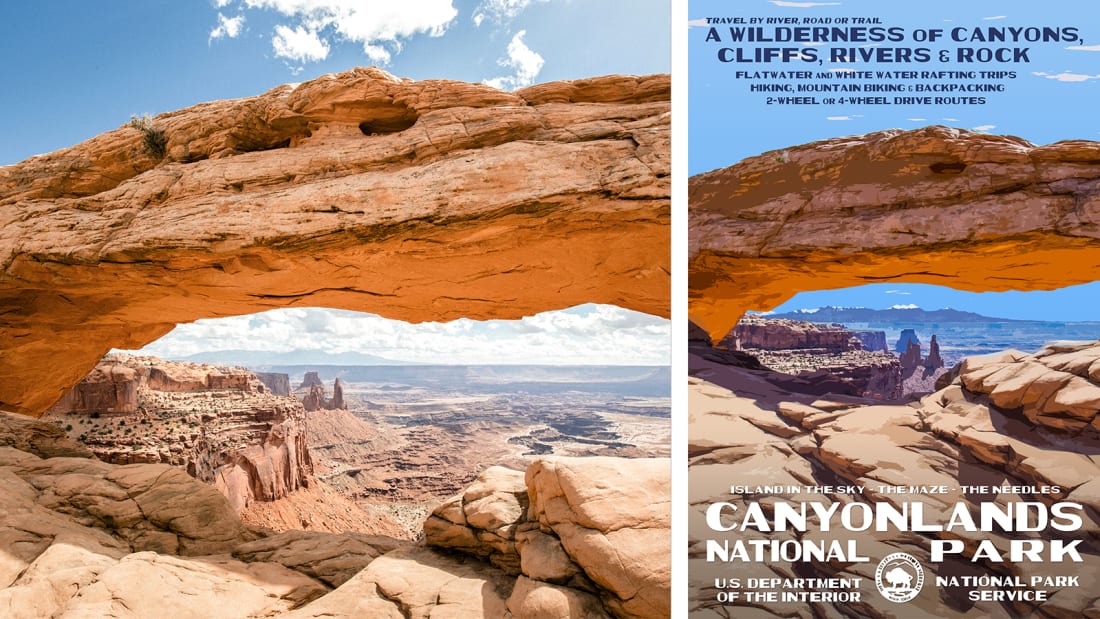

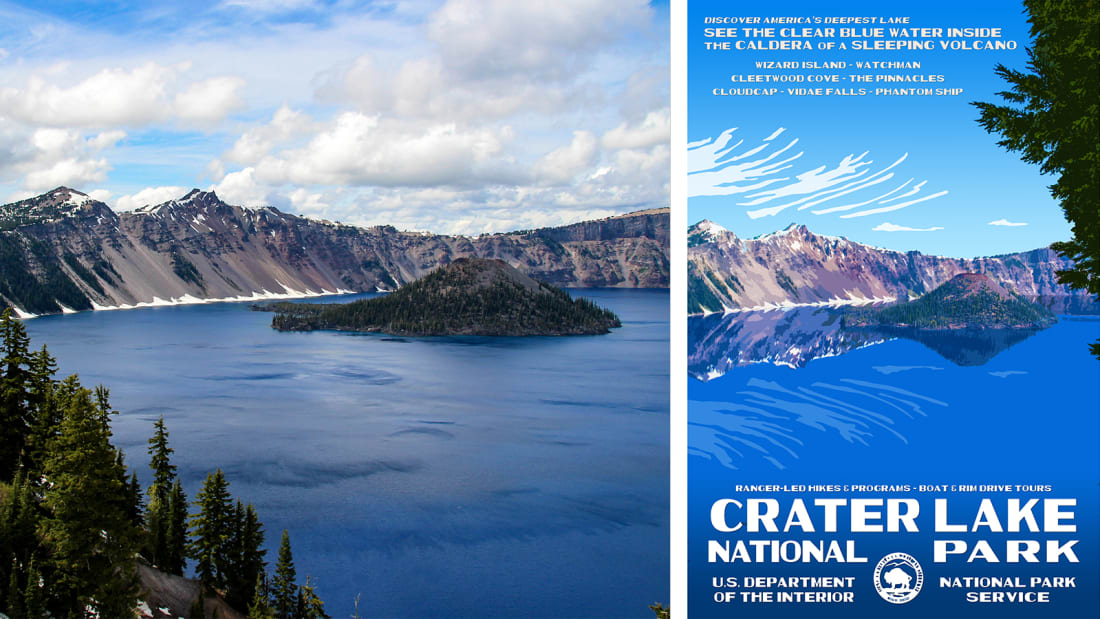

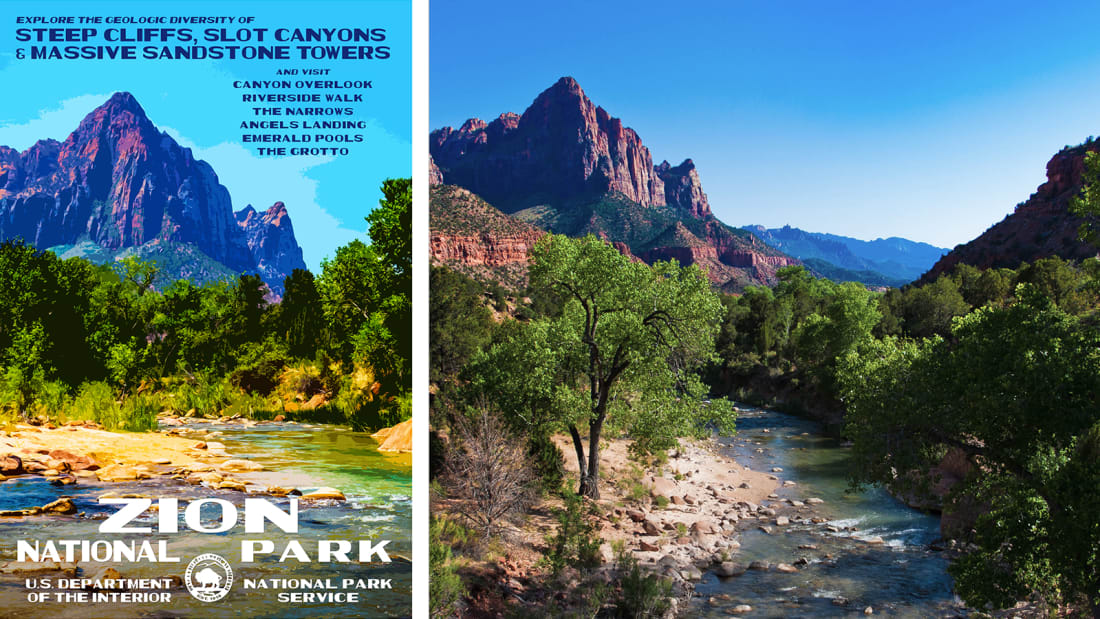

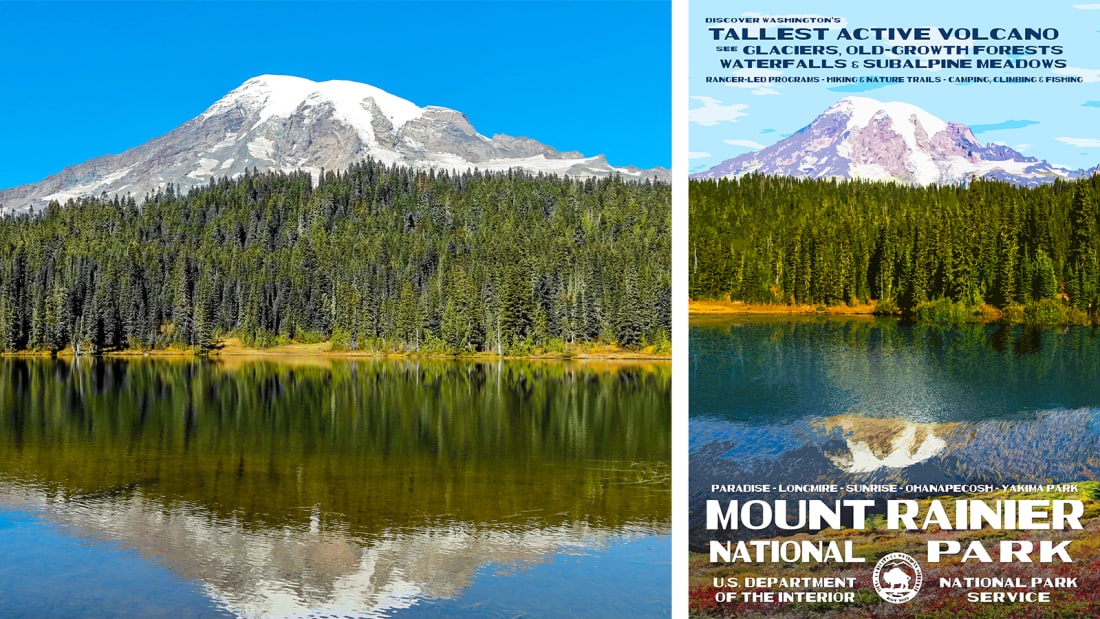

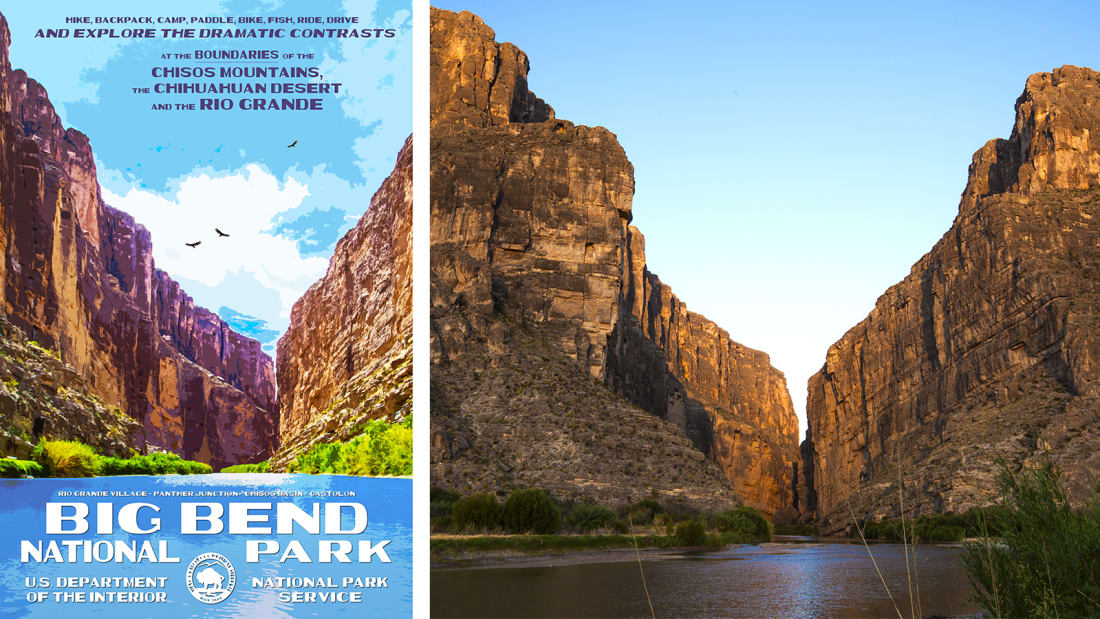

It’s what led him to create the National Park Poster Project, a body of work inspired by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) campaign in the late 1930s, which urged Americans to see and experience the country — perhaps most notably the parks. As Decker visits each one of the country’s 60 national parks, he’s documenting the landmarks, vistas and iconic scenes that make the areas so compelling.

“Everyone should have a chance to see these places,” says Decker, 58, who has already visited and shot 44 of the national parks. “It’s not just the awe-inspiring landscapes. It’s the culture, the history of the country that are often encapsulated there.”

But it was the Organic Act of 1916 that created the National Park Service, “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and wildlife therein, and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

And enjoy they did — at least until The Great Depression put a damper on travel.

The poster campaign also employed the unemployed — by recruiting artists to provide snapshots into the new programs and structures that, if visited, might help pull the country out of The Great Depression.

Between 1938 and 1941, the WPA produced a series of 14 hand silkscreened posters to promote the parks, many of which remain among the most recognizable of the entire campaign’s collection, about 35,000 total designs promoting other WPA projects.

As a child, he may have started with Yosemite, but over the next few years, Decker had visited a half dozen more national parks; over a dozen by the time he graduated high school in 1977.

“I did a lot of traveling with my family, with a camera in my hand,” says Decker, who credits his grandfather with giving him his first Kodak Duaflex at age eight.

“So I kind of had this special view of them. I wasn’t just standing there looking over the rim of the Grand Canyon. I was composing a shot, really seeing it for what it was, rather than just driving by.”

The pivotal moment for the young photographer, however, came in the summer of 1979, when he was invited to study under acclaimed wilderness photographer and environmentalist Ansel Adams.

“That was the catalyst for me,” he says, explaining that he was among the youngest students in a group of 24 invited to the program. “That experience solidified my love of photography in the national parks, and marrying those two things together was a big deal.”

The Colorado-based Decker would go on to pursue a career in photography and graphic arts, producing landscape work and developing multimedia software, presentations and interactive park maps for companies like Rand McNally and some tech start-ups.

But it was another marriage that prompted the poster’s project, when Decker was helping his daughter plan her wedding five years ago.

“She had found this vintage dress, and she asked me to help with the art,” recalls Decker, who designed WPA-style save-the-date cards, place cards and other paper goods to complement the wedding attire.

The response was overwhelming.

“Even though it was her special day, I kept getting a lot of feedback from people telling me I should do more of this type of work,” Decker recalls, pointing out that there’s something about the nostalgia of the WPA to which people are drawn.

“I think it evokes emotion of a time when there was this spirit of adventure. Part of that whole campaign was to encourage people to get out and explore America.”

All Decker had to do to get started was sort back through the thousands of photographs he had already taken during his travels to the national parks. From there, he was able to revisit certain landmarks to get the perfect shots.

Decker reimagines the vintage style by creating a composite photograph, using a combination of different exposures, which are then digitally converted to the WPA look. Muted color palettes provide the backdrop for the simple yet descriptive language that, essentially, tells people what to do once they get to the parks. The Grand Canyon poster, for example, urges viewers to “experience an inspiring landscape with unique geological color and dazzling erosional forms.”

Writing the poster copy, Decker admits, is often the hardest part.

“Part of it is to educate people about the parks and to do what we can to continue to protect them,” he says of the project.

“We’re at a point where it’s key to create this next generation of national parks’ supporters; otherwise, we’re not going to have people in the right positions to make that protection possible.”

The posters are printed on Conservation Papers, a 100% recycled, domestically-produced stock with soy-based inks. Each year, he gives 10% of his proceeds to organizations that support the parks.

Generating excitement among a new generation of parkgoers is one of the main reasons he chooses to give back. Posters sell for $35 each, and he also sells proofs, canvas prints, postcards and other merchandise.

So far, it seems to be working.

“The best call I got was from the Western National Parks Association,” says Decker, who was told that his donation would allow 250 school children to go into the parks and become junior rangers.

The project has also allowed Decker to travel to the furthest reaches of the country, from the ancestral cliffs at Mesa Verde in Colorado to the coral reefs of Virgin Islands National Park.

He appreciates some for their cultural significance; others for the vast landscapes and natural beauty. Still on the list are harder-to-reach locales; Alaska, American Samoa and remote islands near the Canadian border. Those will take a bit more time and planning, although he intends to hit them all.

When his journey is complete, Decker hopes that others will follow in his wake, collecting the posters as souvenirs of their own adventures. And if he has his way, he’ll never truly be finished.