An exclusive CNN investigation has found that some Western governments who pledged to support LGBTQI+ rights have also funded supporters of a controversial bill in Ghana that could introduce harsh sentences for advocating for sexual and gender minorities’ rights.

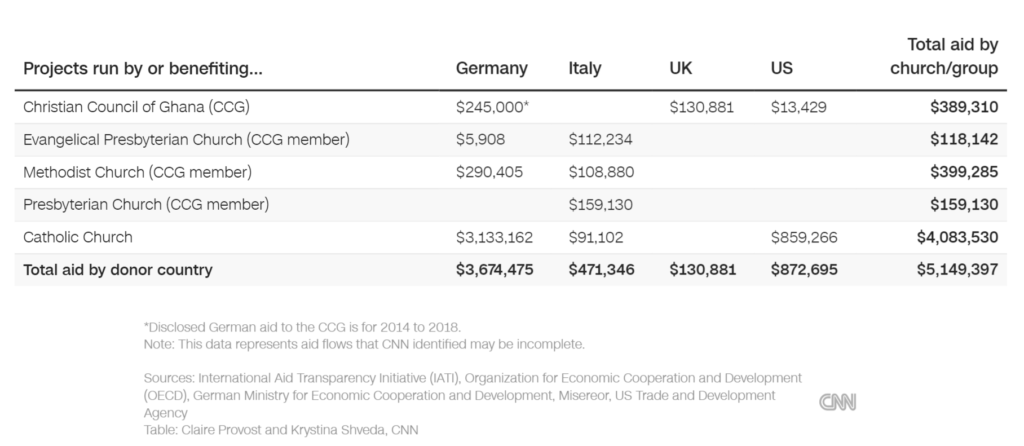

In the five years up to 2021, at least $5 million in aid from Europe and the US went to projects run by or benefiting churches in Ghana whose leaders have backed this bill and have a long track-record of anti-LGBTQI+ statements and activities, according to CNN’s analysis of financial data and communication with the donors.

There is no indication the funding identified went to any explicitly anti-LGBTQI+ activities. However, these religious organizations are now pushing for the anti-LGBTQI+ bill, introduced last year and officially known as the Promotion of Proper Human Sexual Rights and Ghanaian Family Values Bill, to be made law.

In one instance, CNN’s analysis revealed that more than $140,000 of UK and US taxpayers’ money in 2018-2020 went to the Christian Council of Ghana (CCG), an association of 29 churches and Christian organizations, which in 2020 said: “As we indicated in times past, our cultural norms and religious values as a nation do not support LGBTQ rights.”

During that same period, the UK became co-chair of the international Equal Rights Coalition to “protect the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) people” and promote “inclusive development” worldwide.

CNN’s analysis also found that some other members of the Equal Rights Coalition — the US, Germany, and Italy — have funded projects by or for churches in Ghana that have similarly opposed LGBTQI+ rights before, during, and after they benefited from aid money.

CNN exposes how US and European aid benefited churches that oppose LGBTQI+ rights

Human rights advocates called Western donors’ funding practices exposed by CNN “surprising” and “inconsistent.”

“It’s like stating you’re going to go green and then funding the petrol industry,” said Neil Datta, executive director of the European Parliamentary Forum on Sexual and Reproductive Rights.

Donor agencies need to be “more aware that sexual and reproductive rights are contested issues”, and make sure that “they are not inadvertently funding the organizations who are working against some of their other objectives,” he said, calling for stricter “background checks” on potential grantees.

“This reveals inconsistencies in the funding practices of major donors and implicates them as complicit in fostering homophobia and transphobia in Ghana,” said Caroline Koussaiman, executive director of the Initiative Sankofa d’Afrique de l’Ouest (ISDAO), an activist-led fund supporting gender diversity and sexual rights in West Africa. “This is the antithesis of “do no harm” principles.”

“We need donors to support our struggles for liberation, and not directly or indirectly fund anti-gender movements which we know are extremely well resourced,” she added.

Western aid flowed into Ghana despite years of campaigning against LGBTQI+ rights

When presented with the findings of CNN’s analysis, donors whose aid went to projects for or by religious organizations that oppose LGBTQI+ rights said that all such support stopped before the legislation was proposed, or that the funding was given under now-outdated guidelines. Details provided at the bottom of the story.

Yet the CCG, the Catholic Bishops’ Conference and other Christian and Muslim opponents of LGBTQI+ rights are reportedly members of the National Coalition for Proper Human Sexual Rights and Family Values — an advocacy group founded in 2013, that has vocally pushed for such legislation for years.

Its spokesperson, Moses Foh-Amoaning, in 2018 — a period covered by the data CNN reviewed — told local media that the coalition was working on “a comprehensive solution-based… legislative framework for addressing the LGBT problem.”

That same year, its members launched “a three-day fasting and prayer session against homosexuality”, and reportedly organized a camp at an undisclosed location to “treat” and “cure” hundreds of gay people in Ghana.

Also in 2018: £100,000 (about $130,000) of the UK taxpayers’ money went to the CCG with a stated goal of fighting corruption in schools, according to details the UK published in the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) data standard. This was a fraction of a large government fund to support civil society in Ghana, which was managed by a UK charity Christian Aid and that ended in 2020. (It is typical for development assistance to be disbursed by donor governments to for- and non-profit organizations which act as intermediaries, redistributing aid to their partners in recipient countries.)

The US federal government sent more than $13,000 to the CCG in January 2020, IATI records show, for a project to provide shelters to refugees at Krisan Camp in southwestern Ghana.

2016–2020: Anti-LGBTQI+ churches in Ghana benefited from millions in Western aid

Despite pledges to protect the rights of sexual and gender minorities, US and European donors spent at least $5.1 million of taxpayers’ money on projects run by or benefiting Ghanaian religious organizations whose leaders have campaigned against LGBTQI+ rights.

In addition, 208,000 euros (about $245,000) of German aid money went to the CCG between 2014 and 2018, via an intermediary called Brot für die Welt, a spokesperson for the German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development told CNN. Government funding ended in May 2018, but Brot für die Welt continued cooperation with the CCG for almost three more years — until another anti-LGBTQI+ statement to the press in February 2021 that “clearly positioned the CCG against LGBTQI+”, according to CNN’s communication with the spokesperson.

German as well as Italian aid also went to development projects run by or benefiting some individual CCG member churches that have spoken against LGBTQI+ rights, CNN has identified.

Projects of Ghana’s Methodist, Evangelical Presbyterian, and Presbyterian churches received at least $670,000 from these countries via intermediary religious NGOs between 2016 and 2020, according to the most recent available aid data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), corroborated by correspondence with the donor countries.

During that same period, an Evangelical Presbyterian church’s director told local media that his church would continue to be loud and clear in condemning “attempts…to encourage homosexuality”. “No amount of aid promised by the developed world should make Ghana adopt that abominable act,” he said.

Germany, Italy, and the US have also funded projects by or benefiting the Ghanaian Catholic Church.

German Catholic intermediary NGO, Misereor, disclosed spending 2.8 million euros ($3.1 million) of German taxpayers’ money on projects by the Catholic Church’s partner organizations in Ghana between 2016 and 2020. This included $127,000 that was spent on a project with a broad goal of strengthening strategy and management standards for the churches’ development work.

Aid benefiting Ghana’s Catholic Church also included $850,000 from the US. Between 2019 and 2020 this money went to Ghanaian and US contractors for a project whose goal was to transition several dioceses of the Church to solar power, as confirmed by the US Trade and Development Agency (USTDA).

Yet, during that period, the Ghana Catholic Bishops’ Conference issued a joint statement with the CCG opposing same-sex unions. In 2019, the president of the Ghana Catholic Bishops’ Conference called being LGBTQI+ “a lifestyle that is against universal natural values and, certainly, against Ghanaian cultural and moral values.” He urged the country’s president to block the introduction of “evil agenda” in schools, meaning comprehensive sex education including teachings about LGBTQI+ rights. CNN attempted to reach Ghana Catholic Bishops Conference several times for the written story and received no response. To the request for television interview, CNN was informed that “the President is the official spokesperson of the Conference,” but that he would “not be available to grant the interview.”

The CCG and none of the churches in this story responded to CNN’s multiple requests for comment. The spokesperson for the National Coalition for Proper Human Sexual Rights and Family Values, Foh-Amoaning, also declined to answer questions.

Criminalizing same-sex relationships in Ghana

Same-sex relationships were first criminalized in Ghana in the 19th century under British colonial rule. In 2018, the UK prime minister at the time, Theresa May, apologized for such laws, saying “they were wrong then, and they are wrong now.”

In 1960, homosexual acts were made illegal in Ghana’s first, post-independence criminal code, which replaced colonial-era laws but was still influenced by them. This part of the law, however, was rarely enforced.

In its current form, the new bill, brought forth by eight MPs in July 2021, proposes to criminalize not only same-sex sexual relationships and marriages but also identifying as LGBTQI+, promoting and funding of LGBTQI+ groups, and public debate or education on sexual orientation and gender identity. In addition, if the bill were to pass, it would impose medical “assistance” on persons questioning their sexuality, and on intersex children.

The bill drew sharp local and international criticism. Soon after it came before Ghana’s parliament, UN human rights experts called it “a recipe for conflict and violence” that would mandate “deeply harmful practices that amount to ill-treatment and are conducive to torture”, including “corrective rape” for women.

A global LGBTQI+ rights group OutRight Action International recently warned that the bill “goes much further” than any anti-LGBTQI+ law “anywhere in the world.”

The organization said the bill has “contributed to an increasingly hostile climate” and cited “mob attacks, physical violence, arbitrary arrests, blackmail and online harassment, verbal harassment, gang rape” and other abuses reported by LGBTQI+ Ghanaians.

Ghana’s parliament in session.

Leila Yahaya, executive director of queer Muslim organization, One Love Sisters Ghana, told CNN how police raided the paralegal training session her group had organized for activists in the city of Ho, leading to the arrest of 21 people, including herself.

The activists were charged with unlawful assembly and detained for over three weeks, until the case was dismissed for lack of evidence.

Many of those arrested lost their jobs and were ostracized by family members as a result, said Yahaya who received a death threat and was told she needed “a real man” in her life on social media. “I didn’t talk to anybody for more than six months. I was still in my shell trying to recover and pick up the pieces of my life,” she said.

Yahaya told CNN she felt the introduction of the anti-LGBTQI+ bill was “trying to erase” her “whole existence as a human being.”

“Your whole life is full of question marks. What if it’s passed? What if it’s not?” Yahaya said, adding she particularly fears for fellow queer people who may not know their rights as citizens or how to keep themselves safe.

Another LGBTQI+ activist who received threats for his work is Abdul-Wadud Mohammed, communications director at LGBT+ Rights Ghana.

In January 2021, his organization had opened an LGBTQI+ community center in Accra but after just a month in operation it was raided by Ghanaian security forces and shut down following calls from religious leaders, including the CCG and Catholic bishops, for this to happen.

Mohammed said he had to go into hiding for several months to avoid persecution, moving from one house to another with a group of fellow activists until he moved abroad to study.

Why do Ghanaian churches get foreign aid?

While Ghana is a nominally secular country, faith-based organizations wield significant influence on life and politics.

With about 71% of Ghana’s population identifying as Christian, churches are “in every village,” so international development and humanitarian organizations have long recognized the need to work with religious groups. Ghana’s president Nana Akufo-Addo himself acknowledged in a 2018 speech that “the church can be very influential in Ghana” — he then sought to reassure church leaders that his office had “no authority” to allow same-sex marriages.

We must acknowledge that “over the years, many mission churches and African indigenous churches have been involved in development work, such as building primary schools, developing wells, formal and informal education, hospitals and clinics,” professor of gender studies and African studies at the University of Ghana, Akosua Adomako Ampofo, told CNN.

She added that while it is not fair to paint all churches with a broad brush, some have adopted a more restricted understanding of gender and sexuality, which she sees as problematic.

“Within churches, some people’s understanding of the Gospel seems to have led them to believe that if there is a disagreement between the way they understand Christianity and other people’s lives then they have the right to impose their view because they see that as the right view.”

LGBT+ Rights Ghana communications director Mohammed echoed this view, telling CNN: “I understand why they [churches] are getting this money. Donors expect results — and one of the entities that can show results is the church because they are seen as people that are helping the community.”

“It becomes disturbing when this very same aid can be used [indirectly] against marginalized communities,” Mohammed added.

‘I’m mad because these churches are not hiding the fact that they are homophobic’

Asibi (a pseudonym is used to protect her identity) has experienced firsthand the “increasingly hostile climate” members of Ghana’s LGBTQI+ community face.

She had been volunteering to help set up the LGBTQI+ community center in Accra before it was raided. Local TV channels broadcast videos from the center’s YouTube page, and Asibi believes that visibility put her at risk.

According to the 25-year-old, she suspects that a family member took screenshots of her social media accounts — which she used to connect with the queer community — and shared them with other family members. Some relatives then called her mother. At this point, Asibi, who is estranged from her family, began to worry.

One night in her studio flat, she thought that she could hear someone trying to open a window from the outside. The next day, a neighbor told her that a man — who she suspects was a family member — had come by with four others. Asibi immediately went inside, packed a bag, and left her neighborhood. She stayed with different friends for months, until she got a visa and fled the country.

There are many others with stories of intimidation or violence who didn’t want to go on the record. And yet, churches continue to push for harsher treatment by the law. Earlier this year, for example, a Presbyterian Church representative reportedly told a parliamentary hearing on the bill that the current criminal code is inadequate and called for a minimum of three years in jail for “any offense committed under the bill” to serve as deterrent “for people who harbor similar intent.”

“I am mad because these churches are not hiding the fact that they are homophobic,” Asibi told CNN. “I don’t get the justification for funding churches. It further erodes my trust that these international bodies are truly interested in safeguarding the rights of marginalized groups in Ghana.”

What Western donors had to say

When presented with CNN’s findings, a spokesperson for Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) told CNN that the country is aware of “the human rights situation of LGBTQI+ persons in Ghana” and that its intermediary NGOs do not support any projects which endanger the rights of LGBTQI+ communities. These intermediaries, the spokesperson added, are now “seeking to distance themselves from statements made and opinions expressed by the Christian Council of Ghana [CCG].”

However, CNN learned that the NGO intermediary, Brot für die Welt, continues to support projects run by individual CCG members. Those projects are: a three-year grant worth €320,00 for the Methodist Agricultural Program, approved in 2021; a vocational training program by the Presbyterian Church of Ghana which received €460,000 last year; and a three-year €295,000 grant for a health education project by The Salvation Army.

For its part, German intermediary organization, Misereor, continues to use public money to support projects run by or benefitting the Catholic Church in Ghana.

A spokesperson for Brot für die Welt told CNN the organization “strives to engage in constant dialog with local churches” on human rights. “BfdW is aware of some churches conservative and outdated attitude and very much concerned about the discriminating actions in which it sometimes manifests itself,” the spokesperson said.

“Misereor does not support projects that oppose LGBTQ rights in Ghana,” its spokesperson said. “In our internal dialogue with actors in the Church of Ghana, we raise the issue and call for the indiscriminate observance of human rights for all people.”

“Major donors complicit in fostering homophobia and transphobia in Ghana'”Caroline Koussaiman, executive director of the Initiative Sankofa d’Afrique de l’Ouest

Italy’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation told CNN it “is not responsible for the use of these [identified] funds”, saying they go directly from people’s taxes to different religious organizations that distribute the money for development work. The two religious institutions the ministry said sent some of this money to Ghanaian churches, Conferenza Episcopale Italiana and Tavola Valdese, did not respond to CNN’s requests for comment.

The US Trade and Development Agency, which allocated funds to the solar power project benefiting the Catholic church in 2019 and 2020, said: “Legislative and executive branch regulations in place at the time of USTDA’s grant activity would not have prohibited funding by reason of the statements [opposing LGBTQI+ rights] that you provided.”

“We urge Ghana to uphold constitutional protections and to adhere to Ghana’s international human rights obligations and commitments with regard to all individuals, including members of the LGBTQI+ community,” said a spokesperson for the US State Department, which is the agency accountable for the grant the US provided to the CCG. “US government assistance is intended to improve the lives of all Ghanaians, without discrimination.”

A spokesperson for the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO, formerly Department for International Development) told CNN: “The UK has long been at the forefront of promoting LGBT+ rights internationally and we have regularly raised our concerns about the Family Values Bill with the Ghanaian authorities.”

A spokesperson for Christian Aid, the charity that managed UK aid to the CCG, said it is no longer active in Ghana, adding it “takes seriously” its work to promote equality and helps tackle discrimination against LGBTQI+ communities in various countries.

Earlier this year, the UK acknowledged human rights abuses toward gender and sexual minorities in Ghana in a detailed report on the matter for Home Office decision-makers evaluating related asylum claims.

If the proposed bill passes, many LGBTQI+ Ghanaians and their allies would be left with no choice but to try and flee the country.

How CNN reported this story

For this story, CNN first identified churches and church organizations in Ghana that have published anti-LGBTQI+ statements or made such statements to local media — the CCG, its member churches as well as the Catholic church (our list may be incomplete due to an extensive number of religious groups in the country).

We then examined the latest available aid-spending data for Ghana (2016 to 2020) for any mentions of these organizations.

We used two sources for aid data. Donors report their spending annually to the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC). This data is inflation-adjusted and accessible via what is called the Creditor Reporting System (CRS).

Most aid donors and some aid recipients and intermediary organizations also publish details of aid spending in the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) data standard. This data can be downloaded using the online IATI Country Development Finance Data tool, while more details about funding can be found on the d-portal website, an open source platform to explore IATI data.

In the timeframe we examined, OECD data returned mentions of the Methodist, Presbyterian, Evangelical Presbyterian as well as Catholic Churches, in the description section for several projects funded by Germany, Italy and the US. Meanwhile, the CCG appeared in the IATI data, with one project funded by the UK and another by the US.

CNN also gathered evidence of pledges by Western donors to protect LGBTQI+ rights globally before, during, and after these transfers of aid money.

We presented our findings to the relevant authorities and intermediaries in the donor countries and in some cases were able to clarify the value, purpose and timeframes of these projects with them. We also received new disclosures from Germany of funding not picked up in our analysis (with somewhat expanded timeframe).

After categorizing these records as well as the information provided by the authorities and intermediaries, we totaled the amounts of aid money spent on these projects, by relevant church and by donor. All currency conversions are to January 2020 dollars.

It is possible that the CCG and the named churches, as well as the projects they run or are involved in, have benefited from other international aid flows that CNN hasn’t identified (hence the use of ‘at least’ throughout the story). Our analysis is likely limited by limited transparency in aid spending.

MORE: