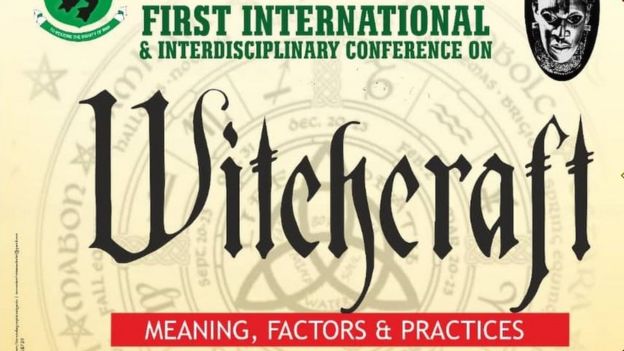

All hell broke loose when the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, announced last month that it would hold a conference on “witchcraft” at its campus in the south-east.

Some staff and students staged protests calling for the two-day event to be cancelled.

Posters appeared around the university campus and online, with angry messages such as: “Witches and Wizards, No Vacancy” and “Don’t Pollute Our Environment”.

The Pentecostal Fellowship of Nigeria (PFN), an influential group which represents clergymen, called on Christians to pray against the event.

“We have had enough of ungodly activities in this country,” said Godwin Madu, a PFN official. “We will not hand [the state] over to witches.”

Every ethnic group in Nigeria has a name for females and males who are believed to openly or secretly collaborate with dark forces to invoke harm upon others.

The English words “witch” and “wizard” are insufficient to convey the depths of evil culturally associated with such people – their “manipulations” are often blamed for a variety of afflictions, from disease to infertility, poverty and failure.

So entrenched is the belief in, and abhorrence of, witchcraft that a section of the Nigerian criminal code, originally introduced under British colonial rule, still forbids its practice, and it is punishable by a jail term.

While reports of convictions are not common, the media regularly features stories of people being branded witches and being brutalised or lynched.

Rights groups condemn the killings, saying superstitious beliefs result in the loss of innocent lives, often those of women and children.

This was not the first time an event associated with witchcraft had led to a furore in Nigeria.

Beliefs about witches in Nigeria:

– Magical powers to fly at night and travel far and wide

– Transform from human beings into animals, birds, reptiles, and insects

– Cause sudden death, disease and impotence

– Cause strong winds, drought and other disasters

– In the Yoruba ethnic group seen as a feminine art; power comes from Esu, the trickery god

– In the Hausa ethnic group, known as Maya, the soul-eater man who can possess people’s souls

Source: Journal of International Women’s Studies

In the early 1990s, Benin City in Edo State in the south was billed as the venue for a global conference of witches.

Nearly 10,000 witches were expected from around the world. Many Nigerians were disturbed by the news.

The drama that ensued is still narrated from pulpits across the country. I have heard it over and over again, from Christians and even from people who do not attend church.

‘God need not waste His time’

The late Benson Idahosa, a popular preacher who is regarded as the father of the Pentecostal movement in Nigeria, called on national TV for the witches’ conference to be called off.

“Not even God can stop it,” responded one of the organisers.

“He’s correct,” Idahosa replied, “Because God need not waste His time when I’m here. I can handle this.”

Benson Idahosa led opposition to a conference of witches in the 1990s

The conference was eventually cancelled. Idahosa gloated publicly that the international witches were unable to convene in Benin City because they were unable to get Nigerian visas.

Apparently, the flamboyant preacher had influenced Nigeria’s then-military ruler, Ibrahim Babangida, who issued the relevant instruction to Nigerian embassies around the world.

The Nsukka conference must have evoked memories of Idahosa’s famous confrontation with witches almost 30 years ago. The protesters and PFN were probably hoping for a similar victory.

But it turned out there were no identifiable witches to forestall. The event was a gathering of intellectuals “to evaluate the belief in witchcraft and its impact on Nigerian society”.

“Apart from rumours about witchcraft, can we intelligently discuss the phenomenon of witchcraft?” commented Egodi Uchendu, a professor of history and international studies and one of the conference organisers.

“Can we delineate its evolving dynamics, especially in regard to human and societal development? What does belief in witchcraft symbolise for civilians, the military, scholars, and others?”

‘Nothing evil’

However, in deference to the public outcry and at the vice-chancellor’s request, the organisers did away with the word “witchcraft” on all publicity material.

The word witchcraft was removed from all publicity material

They also changed the theme to “Dimensions of Human Behaviour”.

The two-day event then went ahead. The keynote speaker had backed out because of the protests but the venue was moved to a larger hall to accommodate the crowd – many were drawn in by the accompanying hullaballoo.

“We didn’t change anything in the conference. We merely modified the title,” said Benedict Ijomah, a professor of political sociology who participated in the conference. “All the papers were the same… You could just modify a sentence and there would be peace.”

Also in attendance at the conference were clergy from local churches. The opening prayer was conducted by a Catholic priest, the proceedings were moderated by an Anglican priest, and music was provided by a choir from the university chapel.

“There was nothing evil,” said Damian Apata, a lecturer in the department of English and literary studies.

But prayer alone is not going to end the belief in witchcraft.

It has persisted “even as people pray against witches and wizards”, said Prof Uchendu.

To combat the beliefs, education levels, therefore, need to improve so that, the professor said, a “pro-positive developmental mindset” emerges in Nigeria.