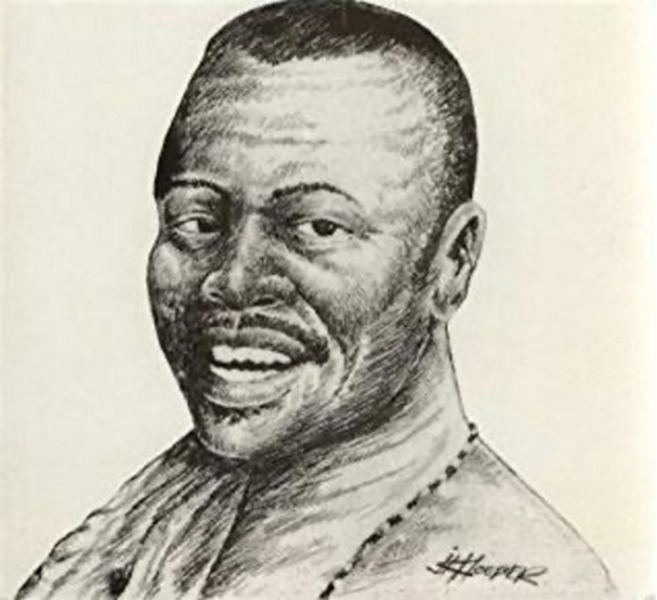

On 14th June, 1993, 31 years ago, the celebrated Director of the School of Communication Studies at Legon was gone, having left a huge academic legacy, and ended his role as a supreme martyr of Ghana’s press freedom.

Ever since he launched his journalistic career in 1968 at University of Ghana, Professor P.A.V. Ansah persistently railed at military dictatorships in very prickly jargon, and Rawlings’ PNDC was no exception. He was instrumental in elevating both the revered Legon Observer fortnightly and the Catholic Standard weekly to their zenith.

The two newspapers were either banned or pressured to fold up by the PNDC government. But he was also columnist for several other newspapers in the early 1990s before he departed. Incidentally, at 27, I was a columnist for the great Catholic Standard, whose editorial board PAVA pivoted.

At the University of Ghana where we became neighbors, I took to Uncle Paul partly due to his admirable writing style, but also he made me comfortable sharing with him one peculiar trait: we were both left-handed. In a culture-sensitive environment where lefties wrap ceremonial cloths in ways others considered clumsy, any such alliance of ‘eccentrics’ was valuable.

All I needed to do during funerals at Legon, was to look around for P.A.V. and quietly sit by him. In case of any commotion by purists, my senior brother would stoutly rise to our defense as odd fellows. When I was appointed Dean of Students at the University of Ghana in the early 1990s, Paul and I got closer, but that was also because he had been appointed as the Master of Akuafo Hall, and needed to discuss student affairs in close set-ups. But there were other matters. Paul would occasionally hobble his way to my office to discuss words he badly needed to sharpen his arsenal and blast dictators in his media write ups. “The People’s Dean, the People’s Dean,” that’s how he called me in his last days, as he trudged cautiously towards the Dean of Students quadrangle. “The People’s Dean, as a linguist please help me to translate these words into English.”

Yes, and what were these?

“The People’s Dean, how do you translate into English the Fanti word, ehua: those children from poor homes who always wanted a little of the food we were eating. How would you translate ehua into English?’ Together we would search through the English lexicon checking words like ‘parasite,’ ‘beggar’ ‘indigent,’… ‘scrounging,’ to no avail. Paul simply said the word was likely to be culture bound, and that there was probably no ehua in England, since the Queen made sure all her children had enough to eat. Asked why he was giving a hell to tyrants in Africa, Paul’s answer was a proverb: “A child who complains too often about stomach ache will see that the enema syringe will have frequent contacts with his somewhere…” (SƐ abofra yƐ me yamu kaw me, me yamu kaw me pii a, bƆntoa mmpa n’ewiei da…)

News of his death in 1993 billowed across the globe. In a day or two, it swept through the airwaves in Norway, France, Kenya, Germany, Botswana, the world. In a Third World where repression-happy regimes were on the prowl for abrasive critics, the conclusion was foregone: P. A. V. Ansah, the celebrated Professor and writer was killed. This was the conjecture of many who heard the news. The state-owned media did not help to abate fears. Their coverage was suspiciously laconic.

But Paul Ansah could easily have been a target to wish away. His acupuncturist, one of the physicians Paul was visiting indeed insisted Paul was not a serious diabetic. “I would rather say he died from unnatural causes,” He also hinted that Paul expressed the fear he might be poisoned if he visited Korle Bu Hospital, and that each time Paul visited his Clinic, he could notice the presence of unusual loafers whom he personally knew.

A great writer and certainly one of the most prolific in the history of Ghanaian journalism was gone; but the state-owned media hushed his departure in a few drab paragraphs. Even the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation in their announcement, forgot a landmark Ansah registered in their own history: their golden jubilee lectures P.A.V. Ansah gave in 1985. His brand of scathing journalism made foes for him inside and outside the perimeters of power. He had received letters and phone calls threatening his life, as hinted by his wife. But illness in his last days made him even more vulnerable: a cocktail of stroke, diabetes, hypertension.

Monday 31st May, 1993. Sitting beside him in his last days, I had with me a questionnaire I long planned administering to him. I had scheduled that mini project for June, for I realized P.A.V.A. in print was little known by his readers beyond being a jolly good brain, always breathing down the neck of the Jerry Rawlings Government.

“Kwesi, I don’t know what I ate today I shouldn’t have eaten; but I feel very very weak,” he said. I said not to worry “Go back to bed. Uncle Paul, I will come another time.”

That was the last I personally saw of Paul Ansah.

On our return from Paul’s burial, Kwame Karikari, Audrey Gadzekpo and I thought the best tribute we could pay our friend was to compile his writings into a book, which was soon published, and relaunched in November 2013, titled Going to Town: The Writings of P.A.V. Ansah.

Soon after his burial something else happened. I had received an unusual visitation from an eminent public figure and business magnate. The man I highly revered told me he noticed a big vacuum in a great newspaper Paul was writing for. On his demise that had implications for the future of the newspaper. Could I take up a column in that paper as a successor to P. A.V.A? The terms for that would be discussed.

I did not even blink an eye and politely said no out of respect and reverence for my good friend P.A.V.A. I simply refused to be a replacement or fill a vacuum a good friend had left.

If anything, I felt duty-bound to help perpetuate the vacuum, and not attempt to blot my friend out of memory.

P.A.V.A. was and still is, irreplaceable.

(Excerpts from ‘Writers in Danger,’ in my book, The Pen at Risk)

kwyankah@yahoo.com