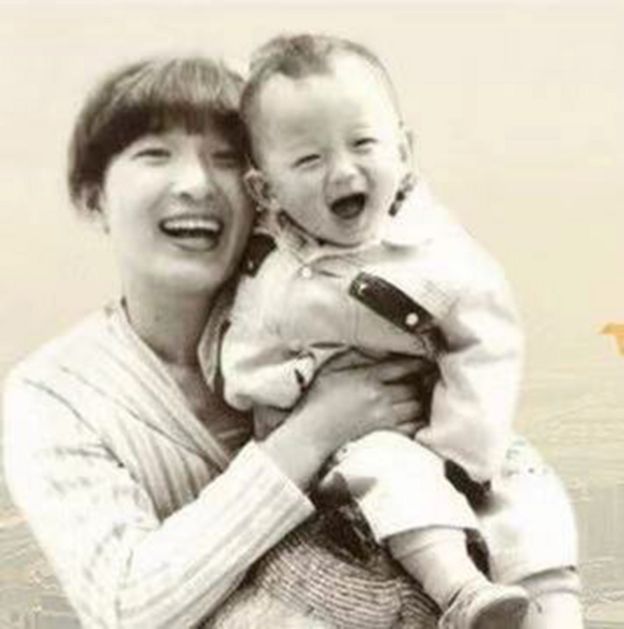

Li Jingzhi spent more than three decades searching for her son, Mao Yin, who was kidnapped in 1988 and sold. She had almost given up hope of ever seeing him again, but in May she finally got the call she had been waiting for.

At weekends Jingzhi and her husband would take their toddler Mao Yin to the zoo, or to one of the many parks in their city, Xi’an, the capital of Shaanxi province in central China. And one of these outings has always remained especially vivid in her memory.

“He was about one-and-a-half years old at the time. We took him to the Xi’an City zoo. He saw a worm on the ground. He was very curious and pointed to the worm saying ‘Mama, worm!’ And as I carried him out of the zoo, he had the worm in his hand and put it close to my face,” Jingzhi says.

Mao Yin was her only child – China’s one-child policy was in full swing, so there was no question of having more. She wanted him to study hard and be successful, so she nicknamed him Jia Jia, meaning “great”.

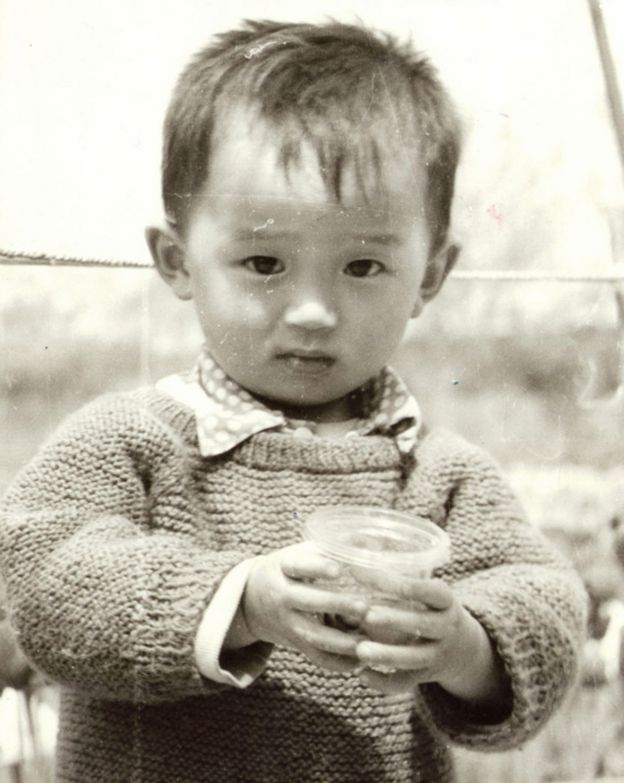

“Jia Jia was a very well-behaved, smart, obedient, and sensible child. He didn’t like to cry. He was very lively and adorable. He was the kind of child that everyone liked when they saw him,” Jingzhi says.

She and her husband would drop him off at a kindergarten in the morning and pick him up after work.

“Every day, after leaving work I played with my child,” Jingzhi says. “I was very happy.”

Jingzhi worked for a grain exporting company and at harvest time she would have to leave town for several days to visit suppliers in the countryside. Jia Jia would stay at home with his dad. On one such trip, she received a message from her employers telling her to come back urgently.

“At that time, telecommunications weren’t very advanced,” Jingzhi says. “So all I got was a telegram with six words on it: ‘Emergency at home; return right away.’ I didn’t know what had happened.”

She hurried back to Xi’an, where a manager gave her devastating news.

“Our leader said one sentence: ‘Your son is missing,’” Jingzhi says. “My mind went blank. I thought perhaps he had got lost. It didn’t occur to me that I wouldn’t be able to find him.”

This was October 1988, and Jia Jia was two years and eight months old.

Jingzhi’s husband explained that he had picked up Jia Jia from the kindergarten and stopped on the way home to get him a drink of water from a small hotel owned by the family. He had left the child for just one or two minutes to cool the water, and when he turned round Jia Jia was gone.

Jingzhi assumed he would quickly be found.

“I thought perhaps my son was lost and couldn’t find his way home and that kind-hearted people would find him and bring him back to me,” she says.

But when a week had passed, and no-one had taken him to a police station, she knew the situation was serious.

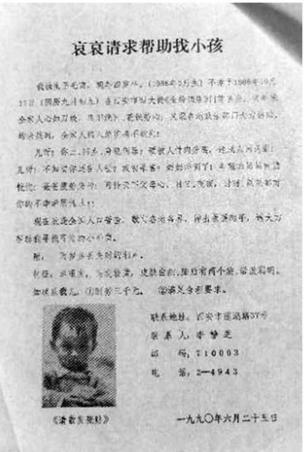

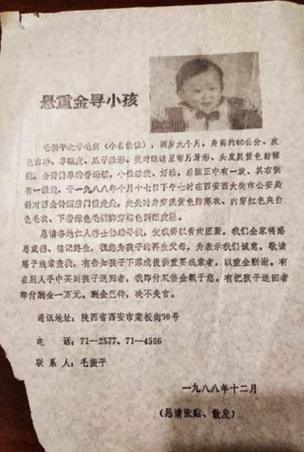

She began asking if anyone had seen Jia Jia in the neighbourhood of the hotel. She printed 100,000 flyers with his picture on them and handed them out around Xi’an’s railway and bus stations, and placed missing person adverts in local newspapers. All without success.

“My heart hurt… I wanted to cry. I wanted to scream,” says Jingzhi. “I felt as though my heart had been emptied.”

She would cry when she saw her missing son’s clothes, his little shoes and the toys he used to play with.

At the time, Jingzhi was unaware that child-trafficking was a problem in China.

The one-child policy had been introduced in 1979 in an attempt to control the size of China’s rapidly growing population and alleviate poverty. Couples living in cities could have only one child, while those in rural areas could have a second if the first was a girl.

Couples who wanted a son to carry on the family surname and take care of them in old age could no longer keep trying for a boy; they would face stiff fines and their additional children would be denied social benefits.

The policy is believed to have contributed to a rise in the number of child abductions, especially of boys. But Jingzhi knew nothing about this.

“Sometimes on TV, there would be notices about missing children, but I never thought that they had been abducted and sold. I just thought they were lost,” she says.

Her first instinct, on learning about Jia Jia’s disappearance, was to blame her husband. Then she realised that they should work together to find their son. As time went on, though, their obsession meant that they rarely talked about anything else, and after four years they divorced.

But Jingzhi never stopped searching. Every Friday afternoon when she had finished work she would take the train to surrounding provinces to look for Jia Jia, coming home on Sunday evening ready to return to work on Monday morning.

Whenever she had a lead – news about a boy who looked like Jia Jia, perhaps – she would go and investigate.

On one longer-than-usual trip in the same year that Jia Jia vanished, she took a long-distance bus to another town in Shaanxi, and then a bus into the countryside in search of a couple said to have adopted a boy from Xi’an who looked just like Jia Jia. But after waiting until evening for the villagers to return from the fields, she learned that the couple had taken the boy to Xi’an. So she rushed straight back again, arriving in the early hours of the morning.

Then she spent hours looking for the flat the couple was renting, only to find out from the landlord that they had left two days earlier for another town. So she hurried to that town and when she got there, again at night, spent hours going from one hotel to another, trying to track them down. When she finally found the right hotel, the couple had already checked out.

Even then she didn’t give up. Although it was now already the middle of the night again, she travelled to another town to find the husband’s parents, but the couple wasn’t there. She wanted to go straight to the wife’s home town, but by this stage she had gone more than two days without sleeping properly or having a decent meal.

After resting, she set off and found the woman and the child. But to her great disappointment, the boy wasn’t her son.

“I thought for sure this child was Jia Jia. I was very disappointed. It had a huge impact on me. Afterwards, I kept hearing my son’s voice. My mum was worried I would have a mental breakdown,” Jingzhi says.

Her son was the first thing she thought about when she woke up each morning, and at night she dreamed he was crying “Mama, mama!” – as he had before, whenever she left his side.

On the advice of a former classmate who was a doctor, she checked herself into a hospital.

“A doctor said something that had a big impact on me. He told me: ‘I can treat you for your physical illnesses, but as for the illness in your heart, that’s up to you.’ His words made me think all that night. I felt I couldn’t go on like this. If I didn’t try to control my emotions, I might really go crazy. If I became insane, I wouldn’t be able to go out to look for my child and one day if my child came back and saw a crazy mother, it would be so pitiful for him,” Jinghzi says.

From that point onwards she made a conscious effort to avoid getting upset, and to concentrate all her energy on the search.

Meanwhile, Jingzhi’s sister packed away all of Jia Jia’s clothes and toys into a box, as the sight of them was causing Jingzhi so much heartbreak.

Around this time, Jingzhi became aware there were many parents whose children had gone missing, not just in Xi’an but further afield, and she began working with them. They formed a network spanning most provinces in China. They sent big bags of fliers to each other and posted them in the provinces they were responsible for.

The network also generated many more leads, though sadly none brought Jia Jia any closer. Altogether, Jingzhi visited 10 Chinese provinces on her search.

When her son had already been missing for 19 years, Jingzhi began volunteer work with the website, Baby Come Home, which helps reunite families with their missing children.

“I no longer felt lonely. There were so many volunteers helping us find our children – I felt very touched by this,” Jingzhi says. There was another benefit too: “I thought even if my child is not found, I can help other children find their home.”

Then in 2009, the Chinese government set up a DNA database, where couples who have lost a child and children who suspect they may have been abducted can register their DNA. This was a big step forward, and has helped solve thousands of cases.

Most of the missing children Jingzhi hears about are male. The couples who buy them are childless, or have daughters but no sons, and most of them come from the countryside.

Through her work with Baby Come Home and other organisations over the past two decades, Jingzhi has helped connect 29 children with their parents. She says it’s hard to describe the feelings she went through when she witnessed these reunions.

“I would ask myself: ‘Why couldn’t this be my son?’ But when I saw the other parents hugging their child, I felt happy for them. I also felt that if they could have this day, I definitely could have this day too. I felt hopeful. Seeing their child go back to them, I had hope that one day my child would return to me,” Jingzhi says.

There have been times, though, when she has almost lost hope.

“Every time a lead turned out to be nothing, I felt very disappointed,” she says. “But I didn’t want to keep feeling disappointed. If I had kept feeling disappointed, it would’ve been hard for me to keep living. So I maintained hope to continue living.”

Her elderly mother also served as a reminder to keep looking for her son.

“My mum died in 2015 at the age of 94, but before she passed away she still really really missed Jia Jia. Once my mother told me she dreamed that Jia Jia came back. She said: ‘It’s been nearly 30 years, he should return,’” Jingzhi says.

When her mother fell unconscious shortly before her death, Jingzhi guessed she was thinking of her grandson.

“I whispered in my mother’s ear: ‘Mum, don’t worry, I will definitely find Jia Jia,’” she says. “It wasn’t just to fulfil my own wish, I wanted to fulfil my mother’s wish and find Jia Jia. My mother passed away in 2015 on 15 January, on the lunar calendar – that’s Jia Jia’s birthday. I felt that it was God’s way of reminding me to not forget the mother who gave birth to me and the son I gave birth to. On the same day one passed away and one was born.”

Then on 10 May this year – Mother’s Day – she got a call from Xi’an’s Public Security Bureau with the amazing news: “Mao Yin has been found.”

“I didn’t dare to believe it was real,” Jingzhi says.

In April, someone had given her a lead about a man who was taken from Xi’an many years ago. That person provided a picture of this boy as an adult. Jingzhi gave the picture to the police, and they used facial recognition technology to identify him as a man living in Chengdu City, in neighbouring Sichuan province, about 700km away.

The police then convinced him to take a DNA test. It was on 10 May that the result came back as a match.

The following week, police took blood samples to do a new round of DNA tests and the results proved beyond any doubt that they were mother and son.

“It was when I got the DNA results that I really believed that my son had really been found,” Jingzhi says.

After 32 years and more than 300 false leads the search was finally over.

Monday 18 May was chosen as the day for their reunion. Jingzhi was nervous. She wasn’t sure how her son would feel about her. He was now a grown man, married, and running his own interior decoration business.

“Before the meeting, I had a lot of worries. Perhaps he wouldn’t recognise me, or wouldn’t accept me, and perhaps in his heart he had forgotten me. I was very afraid that when I went to embrace my son, my son wouldn’t accept my embrace. I felt that would make me feel even more hurt, that the son I had been searching for, for 32 years, wouldn’t accept the love and hug I give him,” Jingzhi says.

Because of her frequent appearances on television to talk about the problem of missing children, her case had become well-known and the media was excited about reporting the story.

On the day of the reunion, China Central Television (CCTV) ran a live broadcast which showed Jia Jia walking into the ceremony hall at the Xi’an Public Security Bureau, calling out “Mother!” as he ran into her arms. Mother, son and father all wept together.

“That’s exactly the way he used to run towards me when he was a child,” Jingzhi says.

Jingzhi learned later that Jia Jia had been sold to a childless couple in Sichuan province for 6,000 yuan (£690/$840 in today’s money) one year after he was abducted. His adoptive parents renamed him Gu Ningning and raised him as their only child.

He attended elementary school, middle school and college in Chengdu city. Ironically, he had seen Jingzhi on television a few years earlier, and thought she was a warm-hearted person. He also thought the picture of her son she showed looked like him when he was a child. But he didn’t make the connection.

As for who gave Jingzhi the lead about her son’s whereabouts, that person prefers to remain anonymous.

After their reunion, Jia Jia spent a month in Xi’an, taking turns staying with his birth mother and father.

During this time, mother and son spent time looking at old photos, which both of them had hoped would awaken Jia Jia’s memory of his childhood before he went missing.

But sadly for them, Jia Jia doesn’t remember anything that happened to him before the age of four, when he went to live with his adoptive parents.

“This is something that makes my heart ache,” Jingzhi says. “After my son came back, he also wanted to find an image or memory of the life he had when he was still with me, but as of now, he still hasn’t found it.”

Jingzhi also realised, on a visit to a scenic spot in Xi’an, that it is impossible to relive the past.

“That day we went to the mountains and on the way down I said, ‘Jia Jia, let Mama carry you.’ But I couldn’t carry him. He was too big.

“I felt if he could return to my side, we could start all over again from when he was a child, we could fill this 32-year gap. I said to my son: ‘Jia Jia can you shrink back to the way you were before? You start at age two years and eight months and Mama will start at age 28 – let’s relive our lives all over again.’”

But Jingzhi knows that in reality this is impossible.

Jia Jia continues to live in Chengdu while Jingzhi still lives in Xi’an. Many people have suggested that she should persuade him to return to Xi’an to be by her side, but even though she would love for this to happen, she says she doesn’t want to make his life more complicated.

“He’s a grown-up now. He has his own way of thinking. He has his own life. Jia Jia has got married and has his own family. So I can only wish him well, from a distance. I know where my son is. I know he’s still alive. That’s enough.”

They are able, anyway, to communicate daily on China’s popular social media app, Wechat.

“My son’s personality is very similar to mine. He thinks of me a lot and I think of him a lot,” Jingzhi says. “After all these years, he’s still so loving towards me. It feels as if we hadn’t been separated. We are very close.”

Jia Jia prefers not to be interviewed and police are not revealing information about his adoptive parents.

As for who took Jia Jia away 32 years ago and how they did it, Jingzhi says she hopes the police will work it out. She wants to see the culprits punished for putting her through 32 years of anguish, and changing her life and Jia Jia’s.

She is now busy creating new memories with her long-lost son. They’ve taken many pictures together since their reunion.

Her favourite picture is the first they took together, the day after their reunion, when they spent time alone in a park.

In the picture, mother and son stand side by side, looking like exact replicas of each other, overjoyed finally to be reunited.

Jingzhi says in the past few years thanks to the efforts of the Chinese government and the Chinese media to publicise the problem, the number of child abduction cases has fallen.

But there are still many families looking for their missing children and many grown children looking for their birth parents. And this means there is more work for Jingzhi to do.

“I will continue to help people find their families,” she says.

Photographs courtesy of Li Jingzhi unless otherwise indicated