The aircraft sitting at peace on the greenery in eerie quietness seems at odds with the thatch-roofed mud houses of Jenna village.

It’s almost like two worlds converging in one place.

The red dirt road in between the community and the park where the aircraft are parked goes as far as the eye can see. Tricycles passing by occasionally send thick clouds of dust billowing into the sky.

Jenna- a village of under 2,000 people- is just on the outskirts of Tamale- the capital of Ghana’s Northern Region. And it is home to Red Clay Studios, a towering space built with red bricks that houses a variety of art installations made mainly from recycled materials that have been redesigned into antique pieces of art.

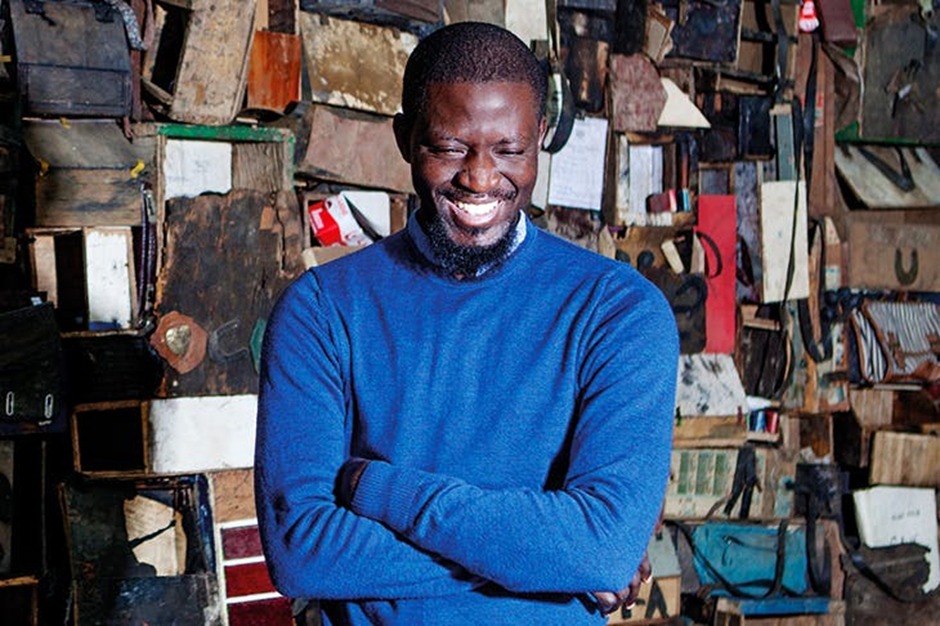

It is owned by celebrated Ghanaian artist, Ibrahim Mahama.

The aircraft, sitting miles away from the closest runway, has become the new centre of attraction, bringing dozens of tourists every day from far and near to this otherwise unknown village.

Abdul-Latif Zakaria, 16 years, is one of the many children from nearby villages who spend time at Red Clay learning about planes and their arts. “Many of the people who live in Jenna have not seen aeroplanes before. They only see it in the sky. Now, they can come here and even sit in a plane,” he says.

Zakaria came to Red Clay because of his father who was one of the first to be employed as the centre’s compound caretaker. He spends the days away from school learning to fly drones, reading about the parts of the aircraft and how to fly it.

“This is a great place. Many of the children who come here go back with smiles. They learn. They learn a lot of things,” he says.

Like him, several other children from Jenna fill the spaces at Red Clay on weekends and after school hours to admire the beauty of the arts and ask questions about how planes work.

“When I was finishing University, I asked myself; is it possible to come back here to build a studio that could inspire young people?” that was the question that Ibrahim Mahama put to himself when he was leaving the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology where he studied for his degree in Fine Arts.

Mahama grew up largely in southern Ghana. He attended some of the country’s best schools. But he was born in the northern regional capital, Tamale where many other children from his generation and those before, saw going to school as a distant luxury.

His father, a civil engineer, one of the very first in northern Ghana, helped build many of the roads there and still lives in Tamale while his mother lives in Accra.

As an artist, Ibrahim is world-celebrated. His works have been exhibited at some of the most prestigious platforms; from the Biennales of Sydney and Venice through the University of Manchester, Documenta 14, Michigan (USA) to the Congo and Tel Aviv, Israel.

In 2018, he met a Swiss-German friend in Accra who had brought a World War 1 model plane to Ghana to fly as a hobby.

He had been denied permit by Ghana’s airspace authorities and so the plane had been left on the tarmac at the Kotoka International Airport for years.

When Ibrahim mentioned his plans to bring old aircrafts for his studio in Tamale, the idea clicked with his new-found friend and he got gifted the abandoned plane.

“We put the entire plane in a tow truck and drove it all the way from Accra to Tamale,” says Mahama.

It used to be the case that the art studios were seen as a place where the artist is at peace and in solitude with himself to create ideas but for Ibrahim, he wants to build something that allows for “a point of reflection, a place where ideas are born and where history comes to life in a very different way”.

In March 2019, Ibrahim opened the Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art (SCCA) as an artist-run project space in Tamale.

Red Clay, named after its exact make and look, is an exhibition space home to research facilities and an artist-residency hub. In Mahama’s own words, this is his contribution to the development and expansion of the contemporary art scene in northern Ghana where art is largely underdeveloped despite its huge potential.

In April 2021, he opened a renovated silo, named it Nkrumah Volini- meaning Nkrumah’s hole- after Ghana’s first President.

“I am not just thinking about artists. I am thinking about thinkers. So that 30 years from now, those thinkers would not make the same mistakes that we made,” he says.

At its heart, the red brick walls at Red Clay hide breathtaking pieces of art installations around different themes. Like The Parliament of Ghosts.

This was originally shown as an installation at the Whitworth Art Gallery, as part of the Manchester International Festival (2019).

The Parliament of Ghosts is a space with four walls and a recreation of the British Parliament with a pool of water in the middle and a lush field of corn planted all around. With this, he is hoping to re-examine the role of modern parliamentary chambers in today’s lived life and also be able to change narratives around political discourse.

In the Parliament of Ghosts, Ibrahim wants people to come in and “examine the state of the places where they live or come from versus the conditions of the places where their governments live and work from”.

Inside another chamber, he has collected hundreds of old and discarded shoemaking boxes and the many locally made tools that cobblers use.

These boxes were previously owned and used by mostly young men who travel from many smaller Ghanaian villages and communities to come work as shoe repairers in bigger cities like Accra and Kumasi.

To get them to Tamale, he had to physically go out and negotiate for them across the country and take with him items contained in these boxes like heels, hammers, brushes, needles, pieces of leather and shoe stockings.

He then has to stitch all of them together into a giant monument almost the size of six passenger vans. He calls this installation Non-Orientable Nkansah.

To go with this work, he adds a series of jute sack paintings, taken from some of the bags that are used to cart cocoa- one of the country’s top exports- distiled into larger architectural showpieces. The morale of this work, according to Ibrahim, is to show how labour and commodities are moved around the world and how that could impact people and livelihoods.

In the shade of the installation’s towering look, Ibrahim speaks to a dozen of children from Jenna who are on a tour.

“This place is for you. It is for you to imagine to be able to do what people see today as impossible,” he tells them in the local Dagbani language.

“I am really interested in the different points of imagination that are borne out of the voids that we create …it allows for certain questions to be raised within the minds of the kids that would ordinarily not be raised if they sat in the square blocks they are used to,” says Mahama.

“I really do not know those questions (and) what they would produce in the future but the most important thing is that it produces different forms of thinking rather than the ones that we inherited,”

It was in 2020, at the height of the covid-19 pandemic, that Mahama moved the planes he had gotten from his Swiss friend to Tamale. Five years before that, Mahama, now 35, earned a million dollars from the sale of his artwork, he decided to purchase some more jettisoned planes left on the tarmac of Tamale’s only airport. He moved all of them together to start his aeroplane installation at Red Clay.

“We want this place to be a safe haven for the artist. To learn about the past, present and future. A site for dialogue and debate, taking historical failures as a starting point for the creation of new ideals, value systems and economic change,” he says.

Mahama thinks of himself as a lucky person. And it is the reason why he is hoping to bring back his work here to try and support young people to attain the highest possible heights.

“If you look at the relationship between the north and south, it doesn’t really make sense. There’s so much wealth in the south but the further north you go, the poorer it becomes,” he says.

The Northern Region, where he comes from, has the lowest level of school attendance of children of primary school age at just 59.4 per cent of children in all of Ghana’s 16 regions. It also has the lowest female literacy rate in the country at 44.3 per cent of young women aged 15–24 years according to the United Nations Children’s Fund.

It is statistics like these that have impoverished communities like Jenna- a trend that could hopefully change if interventions like Red Clay succeed in building up the confidence of young people to be the best, they could possibly be by going and staying in school.

“The children in this village suffer more. We walk to school every day. I think that in the cities, their parents always send them to school,” says Zakaria.

Since Red Clay opened, the young people in the surrounding villages like Jenna who come to see its beauty, say they now have an urge to learn and aspire to many things including a career in aviation.

Like 13 years old Seidu Hadija, whose senior sister fell out of school as a teenager so he could be married off to a man identified by her father. Children- especially girls- have very little motivation to go to school. She remains in school and at her age, she has a year to complete Junior High School.

“When I come to Red Clay, I see a plane and its parts. I used to see planes in the sky now the plane is sitting in my village. I am learning about the parts of the plane and now, I want to be a pilot,” she says.

“It’s not just the children of Tamale. It is for children all over the country. I am hoping that eventually, this thing will go all around the country in different forms and help to reshape the way they think about the world and how they see themselves in the global space,” he says.