In the United States city of Philadelphia in 2018, one in 22 adults was on probation or parole. Among them was LaTonya Myers, who was facing almost a decade of supervision after a string of minor crimes. But a reforming district attorney, who started work the same year, has been reshaping the system – and LaTonya herself has become an activist for change.

LaTonya woke up in the night to the sound of thuds and yells. Her mother’s boyfriend had been growing increasingly abusive and unstable, and now he was dragging their bed out of the apartment and into the passageway outside.

LaTonya crept out of bed and saw the boyfriend shouting and jabbing his finger at her mother’s temple.

“I thought I could protect my mum,” she says. She picked up an aerosol can and hit him with it. He went to a payphone and called the police.

“I thought that all I had to do was tell the truth and they would see that this man was abusing me and my mum,” LaTonya says.

Instead, the police took her away in handcuffs and charged her with first-degree aggravated assault. She was 12 years old.

For three days she sat behind bars and cried the deep sobs of a child who doesn’t know where her family is, or what is going to happen.

“I remember being asked for my social security number. I was 12, I didn’t know my social security number!” she says.

Eventually, she was taken to a juvenile court and given a choice by a lawyer: plead guilty and be released on probation, or go back to jail for another 10 days and fight the case in court.

All LaTonya wanted was to go home with her grandma, who was waiting outside. So she pleaded guilty without appreciating what becoming a convicted felon would mean.

“That experience turned my heart calloused and cold,” she says. “It was a wayward life after that.”

LaTonya found refuge among friends who were just as angry at the world as she was and racked up a string of misdemeanours, including possession of guns and drugs. She fell into abusive relationships.

“Being a female out there selling drugs, a lot of people considered me a pushover,” she says.

LaTonya is 30 now and that childhood conviction remains her only felony (the US term for a crime that is more serious than a misdemeanour). But she’s always felt the weight of it, like concrete blocks on her shoulders.

It has affected her housing, educational and employment opportunities. It has also led to more severe sentences for her misdemeanours, including longer stretches of probation.

Philadelphia, where LaTonya grew up, has unusually high numbers of people on probation or parole – that is, a period of supervision after early release from prison. In fact, it has been described as the “most supervised” big city in the US.

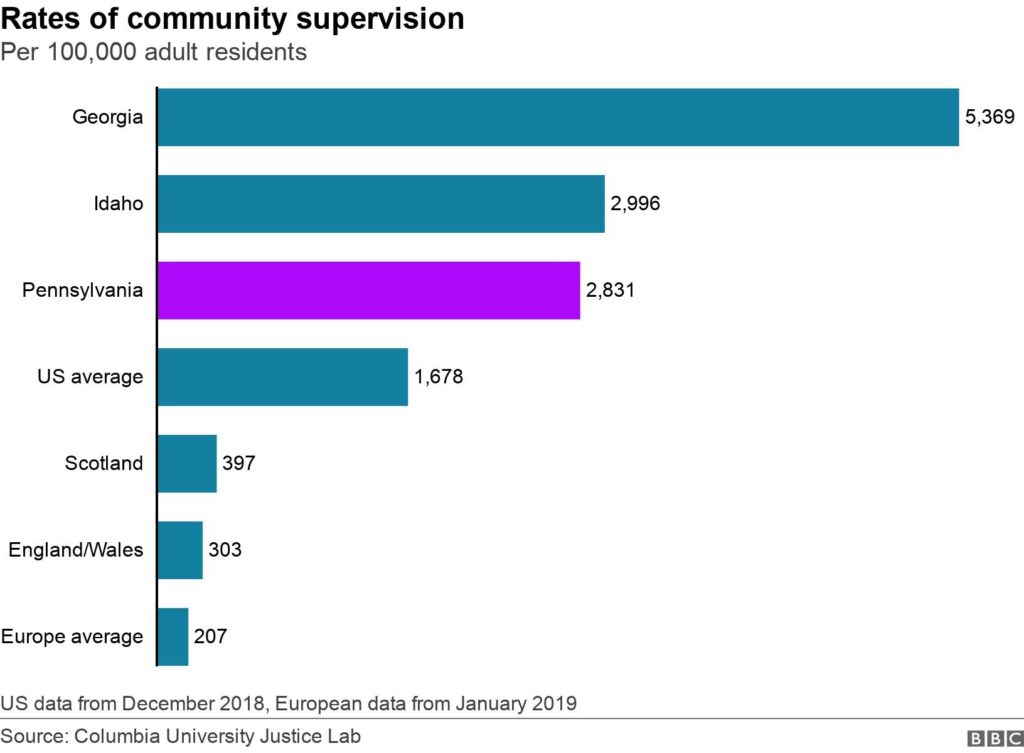

In 2018, one in 22 adults – and one in 14 African Americans – was on probation or parole, according to research from the Columbia University Justice League. Pennsylvania, the state of which Philadelphia is a part, is currently the third most supervised state in the US.

One reason for this is that the length of probation in Pennsylvania can be just as long as the prison sentence – a 20-year prison sentence can come with 20 years of probation added on.

“This is a sharp departure from most other states, where probation time has set caps – usually one cap for all misdemeanours, and another cap for all felonies,” says Kendra Bradner, director of the Probation and Parole Reform Project at Columbia University.

Another difference between Pennsylvania and most other states is that people convicted of more than one offence can be made to serve each sentence in turn, instead of concurrently. And a judge can extend a period of probation if someone breaks the rules.

“It’s a triple threat – long sentences possible to begin with, that can be stacked one after the other, and then extended further for rule-breaking,” says Bradner.

In 2018, more than half (54%) of state prison admissions were for violations of probation or parole.

But in November 2017 a liberal lawyer who promised far-reaching reform of the criminal justice system, was elected as Philadelphia’s district attorney (DA).

Larry Krasner has called mass supervision “the evil twin of mass incarceration” and he took aim at both.

LaTonya followed Krasner’s campaign from prison, where she was awaiting trial in a case resulting from false charges made by an ex-girlfriend. This time she had steadfastly refused to take a plea deal and was determined to fight the case.

At the age of 26, LaTonya had already been living independently for 10 years.

She had graduated from high school while successfully completing a drug treatment programme. After that, she almost got a job as a university lab technician – the interviewers could see how bright she was, but the offer was withdrawn when they discovered her criminal record. She took a minimum-wage job working as a security guard instead.

“It felt humiliating for my intellect to be overlooked and instead I had to play into this macho stereotype,” she says. “I remember thinking, ‘I’m never going to be able to save any money or support my family – I’m stuck,’ and I felt broken.”

LaTonya was always acutely aware of the thin line separating the haves and the have-nots. She describes her own neighbourhood, south-west Philadelphia, as “poverty”, where children have to grow up fast to survive. More than half of her friends never made it to adulthood.

But just a few blocks away is Pennsylvania’s Ivy League university and LaTonya would enjoy riding her bike to the area to take in the atmosphere.

“There were book stores, people lying in the grass and reading, people playing frisbee,” she says.

LaTonya would look up at the statues and later learned the esteemed sociologist and African American activist, WEB Du Bois, walked those same parks. She says it gave her a love of learning, even though university wasn’t an option for her.

Now in custody again, LaTonya spent as much time as she could studying case law in the library.

“I learned how to impeach a witness and worked out how to win my case – my attorney became quite irritated because I kept sending the case law,” she says.

She also helped other inmates write letters to their judges.

“It was like a firestorm through the jail – everybody sending letters and filing motions,” she says.

LaTonya was finally acquitted after nine months in custody and this proved to be an important turning point.

After her release, she landed a job at the public defender’s office, which provides legal representation to those who cannot otherwise afford it. She was its first ever bail navigator, supporting people likely to be held in custody because, unlike wealthier defendants, they couldn’t pay to be released on bail.

Her task was to gather information about the defendant and the alleged crime – including, for example, whether the individual had been acting in self-defence – which might help the public defender dissuade the judge from setting bail at an unaffordable level.

“I would ride the lift with lawyers and correctional officers who had told me I deserved to be in prison or didn’t have a case,” she says. “I stuck my chest out and held my head up as high as I could. That was a full-circle moment.”

On taking over as DA in January 2018, Krasner fired 31 prosecutors from the DA’s office. The next month, he announced that people caught in possession of marijuana would no longer face criminal charges, and took steps to limit the use of “cash bail”, arguing that it is unfair on the poor to spend time in detention when others are released.

Krasner also instructed prosecutors not to seek probation of more than one year for misdemeanours or three years for felonies, arguing that the first two-to-three years of supervision generally help to rehabilitate a person, but any longer can do the opposite.

When LaTonya was released, though, she faced at least 10 years of weekly meetings with a probation officer because of her earlier misdemeanours. Along with that came random visits to her house and her workplace, drug and alcohol tests whenever she was summoned, and a ban on leaving the city without permission.

“I felt flustered and frustrated because it was like I had one foot on the street and one foot in jail,” she says.

She even had the surreal experience of earning a citation from the mayor for her advocacy work and being threatened with jail by her probation officer, because the award ceremony clashed with her weekly appointment. It made LaTonya feel as though the officer was more interested in her failures than her achievements.

Krasner’s opponents say that Philadelphia is a safer place because of its strict probation regime, but Sangeeta Prasad, an attorney in the DA’s office, argues that this is a mistake.

“High levels of supervision make Philadelphia less safe because they result in jail sentences for minor mistakes while under supervision and destabilise work and housing opportunities,” she says.

For example, even though possession of cannabis is no longer prosecuted in Philadelphia, a positive drug test can be a violation of probation rules, resulting in a return to jail.

For employers it is inconvenient to accommodate a worker’s meetings with probation officers, or random workplace checks. And landlords who carry out background checks on tenants may refuse to let a property to someone on probation.

“By continuing to over-police and over-supervise the poorest black and brown communities in Philadelphia, we keep Philadelphians poor. This does not make us safer,” says Prasad. “Every additional jail or prison stint weakens your options for work and positive community ties; each time you are sent to jail or prison, you become more vulnerable to taking part in future criminal activity.”

Courts can also demand that someone “stay away from criminal activity” or “stay away from criminal conduct”, she points out, with the result that someone may have to move out of a family home where someone has a prior criminal conviction.

In April this year, the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office announced that since 2018, the number of people under supervision in the city had fallen by one-third, from 42,000 to 28,000.

The average supervision term declined by about 10 months over the same period, “with no measurable impact on recidivism,” according to the report.

Racial disparities in sentencing have also fallen. Previously, black defendants were kept on probation on average 10.8 months longer than white defendants. Now, the average difference is 5.2 months. The DA’s office estimates that to date the new approach has resulted in an estimated 95,600 fewer years of supervision.

In the summer of 2019, LaTonya successfully appealed to be released early from probation.

It took a while, though, for her to not instinctively feel she had to ask permission just to go somewhere or do something.

“It’s hard because once you’re free, you’ve still got to teach yourself mentally to be free,” says LaTonya.

She left her job at the public defender’s office just as the pandemic hit, in March 2020, to spend more time working on her own non-profit organisation, Above All Odds. The initiative supports and advises people who have just left prison and educates them on their civil rights – particularly women and the LGBTQ community.

“I want to make sure people know about their voting rights and their right to petition for early termination of probation, which we can support them with,” she says.

When she has spoken about her achievements she’s been told she is an “outlier” and that her story isn’t representative of the thousands of others on probation. But she insists her story is not that remarkable.

“Set people free and they can thrive – rather than be in constant survival mode with the threat of jail hanging over their head like an axe,” she says.

Last year she threw a Probation Awards Ceremony to give people on probation a rare moment of recognition. She invited judges, prosecutors and probation staff in the hope it would challenge their perception of ex-prisoners.

“Think about everything the DA and the judge thought about you. Let them know that you are not throwaways, that you are not incorrigible,” she tells the prize winners before they enter the hall.

Up on stage, LaTonya is all broad smiles, warm hugs and shoulder squeezes. But as well as her advocacy work she also wants to spend some time looking after herself, making up for the years when she wasn’t free.

“I want to fly a kite, I want to go white-water rafting, I want to dig my feet in some sand. Things I didn’t think I’d be able to do because I was so entangled in the system.”