Dorothy Masasa happily walks down a dirt road on a sunny afternoon, her baby securely strapped on her back.

Just six months ago the 39-year-old, originally from southern Malawi’s Thyolo district, was in Kenya for life-saving radiotherapy.

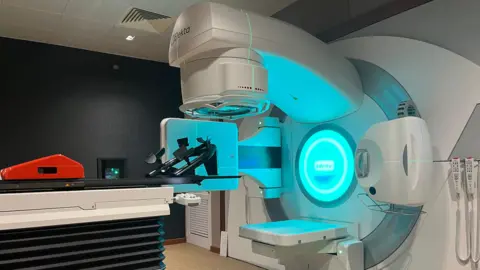

Malawi has only recently received its first such machines, so other women with cancer may no longer have to travel abroad for treatment.

“I was registered as an emergency case after doctors discovered I had cervical cancer while 13 weeks pregnant. They told me these two things don’t go together,” the mother of three tells the BBC.

She says the doctors in Malawi told her that she could have an operation to remove the cancer but this would terminate the pregnancy, or she could have chemotherapy but this would risk the baby being born with a disability.

She opted for chemotherapy until the baby was born via Caesarean section – without any disability.

Her uterus was removed in the same operation.

Before the diagnosis, Ms Masasa experienced cramping in her lower abdomen, bleeding and a foul-smelling vaginal discharge that just wouldn’t go away. At first doctors thought it was a sexually transmitted infection.

But despite the chemotherapy and the operation, she still needed further treatment to cure the cancer – treatment which wasn’t available in Malawi until earlier this year.

She joined a group of 30 women who were taken to a Nairobi hospital in Kenya by the aid agency Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) to undergo radiotherapy to kill the cancerous cells.

This was the first time she had travelled on a plane, so she was quite worried and also reluctant to leave her newborn baby behind.

“But because I was going there for treatment, I encouraged myself that I should indeed go and get treatment and that I will come back home healthy and happy.”

When the BBC visited her at the hospital, Ms Masasa was still frail from the effects of the treatment, having lost weight and her hair.

She is one of 77 patients who were airlifted from Malawi to Kenya for cervical cancer treatment since 2022.

Sixty years after gaining independence from the UK, Malawi only installed its first radiotherapy machine, at the privately owned International Blantyre Cancer Centre, in March this year, marking a huge step in the country’s healthcare system.

More machines arrived in June and are due to be placed at the National Cancer Centre still under construction in the capital, Lilongwe.

Although Malawi still has a long way to go to provide comprehensive cancer treatment, it is ahead of many other countries in the region.

In sub-Saharan Africa more than 20 countries have no access to radiotherapy, which is critical to fighting cancer.

This means patients are forced to undertake expensive and exhausting journeys for treatment.

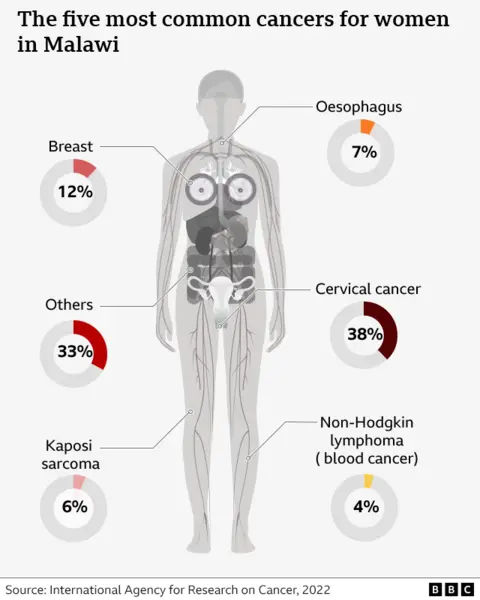

Cancer of the cervix is the fourth most common cancer among women worldwide, with an estimated 660,000 new cases and 350,000 deaths reported in 2022, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

All but one of the 20 countries with the highest rates of cervical cancer in 2018 were in Africa, according to the World Health Organization.

This is down to a lack of access to preventative human papillomaviruses vaccines (HPV), adequate screening and treatment, meaning many women are treated late.

The Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital (QECH), Malawi’s oldest and largest government-owned treatment centre, receives a huge number of cervical cancer patients from across the country.

An obstetrician and gynaecologist at the hospital, Dr Samuel Meja, says cervical cancer is a big problem for most countries in the region.

“Poor access to screening, and the scourge of HIV, which has been ravaging most parts of sub-Saharan Africa, have worsened the situation,” he says.

In 2018, Malawi was only second to Eswatini in southern Africa, which had the highest rate of cervical cancer in the world.

Outgoing WHO regional director for Africa, Dr Matshidiso Moeti, says that globally a woman dies of cervical cancer every two minutes. Africa accounts for 23% of the deaths.

In order to reverse these grim statistics, Africa has seen massive campaigns to vaccinate girls against the HPV that causes cervical cancer.

Lesotho has reached an exceptional 93% coverage after vaccinating 139,000 girls against HPV.

But stigma around cervical cancer in various African countries has affected the numbers of people getting vaccinated.

In Zambia, for instance, talking about anything gynaecological is frowned upon.

In Malawi, Dr Meja says that cervical cancer screening has been introduced.

“This is a very simple strategy that identifies women at risk and you treat them before they become cancer patients. This investment is what we need to make as a nation before it gets out of hand,” he says.

As for Ms Masasa, she is now back at her home in Malawi.

The treatment she received in Kenya has given her a new lease of life. Her hair has grown back, she can walk around with her baby on her back, tend to her cow, and work in the fields.

She says she now knows that cervical cancer can be treated and that the vaccine can help other women avoid the disease, so has no doubts about vaccinating her daughter.

“Cervical cancer took me through a hard phase and I wouldn’t want my daughter to go through the same,” she says.

“There is a huge difference between how I was then and how I am now. I feel so happy that I am healed.”