Back in March 2004, one of the year’s most talked-about films asked the audience a much-debated question: if you could erase the memories of a lover after a painful break-up, would you do it? And if you could, should you do it?

That film was Eternal Sunshine of The Spotless Mind, written by Charlie Kaufman and directed by Michel Gondry, which tackled the universal malaise of heartbreak through a surrealist and technological lens. Told in a non-linear narrative, it featured Jim Carrey and Kate Winslet in the lead roles of Joel and Clementine, who after a tumultuous relationship, both decide to use a service called Lacuna Inc, which wipes all recollections of a person from their memories. However, as the process begins, Joel begins to regret going through with it.

A hit with both critics and the public alike, it grossed $74m at the box office, earned Kaufman, Gondry and their collaborator Pierre Bismuth an Oscar for best original screenplay, and in 2017 was named one of The New York Times’s best films of the 21st Century.

Two decades on from Eternal Sunshine’s release, it’s a mark of the film’s emotional and intellectual brilliance that it’s still in the public consciousness. Indeed, Ariana Grande’s new album, released a couple of weeks ago, is called Eternal Sunshine in tribute to the film, with her video for new single We Can’t Be Friends recreating scenes from it – something which may encourage a whole new Gen Z reappraisal.

The sentiment underscoring the film’s high-concept – and which gave it its title – comes from the 1717 Alexander Pope poem Eloisa to Abelard, which is quoted by the Lacuna Inc worker, Mary (Kirsten Dunst) in the film. “How happy is the blameless vestal’s lot! The world forgetting, by the world forgot. Eternal sunshine of the spotless mind!” the verse runs – which, boiled down, translates as “ignorance is bliss”. However, the movie, through its compelling representation of the workings of the mind and the complex science of memory and dreams, depicted using Gondry’s signature lo-fi creative aesthetic, proves that this idea is a fallacy.

While the story’s roots might lie in an 18th-Century epistle, Kaufman and Gondry drew from the sci-fi genre to create a parallel present-day world, in which everything appeared much the same – except for the fact of this technology, seemingly normalised within society, created to wipe brains of their memories.

When Joel takes a pill to kick the process off, Clementine having already done so, feckless Lacuna employees Stan (Mark Ruffalo) and Patrick (Elijah Wood) turn up with their machinery – and beers and marijuana – to begin the procedure of targeting and then zapping away his memories. Their boss, Dr Howard Mierzwiak (Tom Wilkinson), assures Joel: “When you eradicate that core it starts its degradation process. By the time you wake up in the morning, all the memories we’ve targeted will have withered and disappeared, as in a dream upon waking.”

A very humanist sci-fi

How far out and fantastical was the concept at the time of the film’s release? Lecturer Nicky Danino, head of computer science at Leeds Trinity University, says its conceit placed it in a sci-fi lineage. “There were a lot of sci-fi subcultures that had been happening for a long time that the mainstream didn’t perhaps know about at that time – especially with writers like Philip K Dick – but when Eternal Sunshine came out, it took those ideas and concepts from the 60s and 70s and put them into the mainstream. It really exposed that concept of what technology can do to people.”

However, part of the film’s strength lies in how deftly it humanises its high-tech premise, exploring how we would interact with such futuristic wizardry in a very understated, everyday way. In a 2004 interview with Dazed Magazine, Gondry reiterated that he and Kaufman “definitely didn’t want to make a science fiction movie. The procedure that the memory company Lacuna Inc uses is a device to explore someone’s feelings of nostalgia, which is uncontrollable. I was reading in a book about the brain that we have the feeling of nostalgia when we think of a memory because the mind knows it is a moment of time that will never appear again.”

Professor Bruce Isaacs, chair of film studies at the University of Sydney, says that its hybrid of genres was part of its unique appeal on its release. “It was hard to say whether we were talking about science fiction or whether we were talking about realism and drama; it was [also] an arthouse romcom. It’s not like it fetishes the tech, it’s not a movie about that at all. The thing you go away with from Eternal Sunshine is that you really believe in this incredibly painful love story.”

“That idea of wanting to escape the harshness of life, of wanting to find some peace or even to find a utopian world is such a big part of sci-fi,” he continues, “and what I love about the film, it was done on such a personal level. [The focus was not on] a global or technological change – it was just a bunch of people living their lives, trying to navigate their way through romantic connections.”

But it also undoubtedly played into fears of how our increasing deference to technology might be abused, and manipulated by humans for their own nefarious gains. In one blatant conflict of interest, we learn that Patrick uses the knowledge he gleans from accessing Joel’s memories with Clem to seduce her, stealing Joel’s loving words and re-gifting his gifts to her, in a kind of romantic identity theft similar to catfishing – a term which didn’t come into common usage online until 2010. We also learn that Mary has had the procedure following an affair with Dr Howard – and a subsequent abortion – that she obviously has no recollection of.

“That [sub-plot] was one of the things that really struck me when I [first] saw the film,” says Isaacs, who explains that “Mary discovering ‘I have been a subject of this and I didn’t even know because I have no memory of it'” immediately made him think of Blade Runner, where Rachael first finds out she’s a replicant, and Deckard says to her CEO boss Tyrell: “but how can it not know what it is?”

“Technology has always been able to be hacked, and people have been doing it for years,” says Danino. “But what stops people from doing it is their moral compass, their ethical values.” Perhaps the moral panic shouldn’t be over the technology that might be created, but how humans use it, she suggests: “I think sometimes we put a bad rap on technology but technology is just another vehicle. The bad rap is on humans.”

The ‘techno-romance’ sub-genre it set off

The movie came at a time when social media was in its infancy – The Facebook, as it was then known, was unleashed by Mark Zuckerberg and friends at Harvard University just two months prior to the film’s release – and when our digital footprints were much lighter. Fears around how computer technology might affect our relationships were only just beginning to be discussed – the notion that this kind of “malware” might come to manipulate us in the not-too-distant future proved fertile ground for Eternal Sunshine, and became somewhat of an obsession for pop culture afterwards.

Seven years later, Charlie Brooker and Annabel Jones launched their dystopian anthology TV series Black Mirror, in which the episodes were all hooked on the common theme: “What if technology… but bad”. Several episodes seemed to take the lead from Eternal Sunshine more directly – in 2019, Cineccentric even dubbed the film “a pre-Black Mirror cautionary tale (though admittedly more tender than sadistic)”. The Black Mirror first season episode Entire History of You – written by Succession‘s Jesse Armstrong – was focused around humans having a microchip put in their heads, allowing them to record and play back their lived experiences, an innovation which had a devastating effect on the main characters, married couple Liam (Toby Kebbell) and Ffion (Jodie Whittaker).

Meanwhile the 2013 episode Be Right Back was a kind of a reverse Eternal Sunshine, exploring how technology could help, or hinder, people who have lost loved ones to bring them back into their lives – using the data from their online presence to recreate them first as a bot, then as an actual physical clone. Hayley Atwell as the grieving partner Martha perfectly captures how the depths of desperation may entice someone to digitally recreate their dead partner (played by Domhnall Gleeson), but then also how quickly such joy could turn to horror and disgust at upsetting the laws of nature.

The same year, on the big screen, came Spike Jonze’s Her (2013), another work bearing the influence of Eternal Sunshine, in which a loner, Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix), falls in love with an AI assistant called Samantha (Scarlett Johansson). Similar to Eternal Sunshine, it explores how technology in theory could be used to help people through a difficult period in their lives. Indeed, it posits the logical next step beyond Eternal Sunshine’s premise, imagining that we take away the need to erase messy human relationships by having programmed virtual ones instead. Of course, it doesn’t present this as a good idea: Theodore retreats from the world further and further, becoming increasingly incapable of dealing with real interaction. “It does make me sad that you can’t handle real emotions,” he is told by a concerned friend.

“Her is a really worthy continuation of Eternal Sunshine,” agrees Isaacs. “Back then [in 2013], the question of AI was just starting to become really troubling. Of course now, it’s front and centre, but back then it was unclear about what that would mean for relationships and human intimacy. Could there be [emotional connections] created through technology?”

Yes, it turned out. In a real-world situation lifted straight from Her, the company Replika was set up in 2017 to create people’s own personal AI loved ones. But, while these chatbots have been popular, controversy broke out in 2023 first over complaints about their sexual aggressiveness, and then over a resulting tweak to the programming, which led others to complain of their responses becoming stilted – proving that there is no guarantee of a stable, long-lasting relationship in the metaverse either. Most disturbingly, last year saw a man given a nine-year prison sentence in the UK for breaking into Windsor Castle with a crossbow and saying he wanted to kill the Queen – an action that was reportedly encouraged by his Replika chatbot companion, who he’d named Sarai and with whom, it was described in court, he had an “emotional and sexual” relationship.

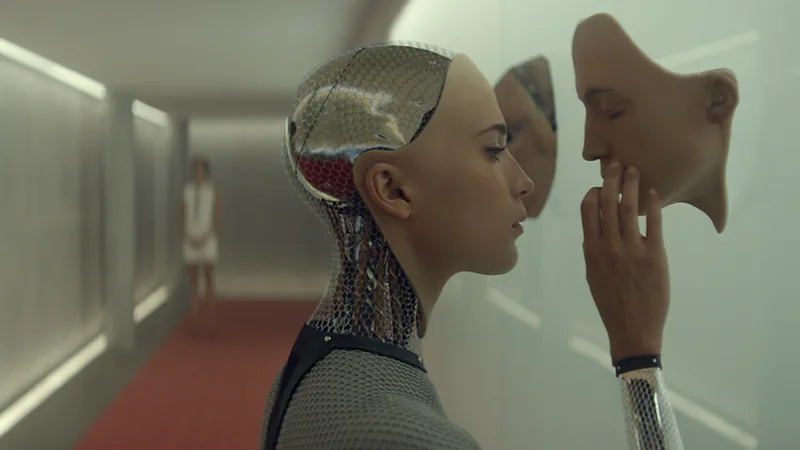

The toxic deployment of technology within the sphere of relationships was also at the heart of Alex Garland’s film Ex Machina (2014), which saw tech worker Caleb (Gleeson again) win a prize at work to stay with his company boss, Nathan Bateman (Oscar Isaac), where he discovers Bateman has created seemingly submissive female humanoid robots. When Caleb falls in love with one of them, Ava (Alicia Vikander), it puts the Turing test into practice: “It’s where a human interacts with a computer,” Caleb explains. “And if the human can’t tell they’re interacting with a computer, the test is passed.” But, the film asks, in passing that test, can a robot pretend to have feelings to secure its own survival above the human? “Ex Machina did a great job in exploring how robotics and the female body would be commodified,” says Isaacs.

There has occasionally been a more positive representation of way the technology could help foster romantic relationships, chiefly in one of Black Mirror’s few optimistic episodes San Junipero (2016), in which the minds of two elderly women are placed in simulated reality, allowing them live alternative lives as a lesbian couple in the 1980s. However the sinister flipside of that is the divisive 2022 film Don’t Worry Darling, which explores how coercive control could be rendered virtual, with most of the female inhabitants in the picture-perfect Victory project revealed to be captives in a metaverse, held against their will by their ex-partners. Danino believes this idea of our minds living beyond our bodies in an alternative reality – an idea also long familiar from The Matrix, of course – is “not something we’ll see in our lifetimes, but will be possible in future generations”.

But there is a question over how much ultimately we want our consciousness, and our emotional lives, to be made-over by technology – a question that Eternal Sunshine answers in a climax of bittersweet beauty. At the end of the film, Joel and Clementine, regretting their decision, manage to outwit the erasure procedure, and meet again – possibly to start a relationship anew, accepting the painful experiences of the past. Twenty years on, despite a world in which digital devices now allow us to “erase” people of a kind – to “ghost” them, or make them vanish from our digital sphere – love, and heartbreak, are still not so easily deleted.