As the era of cheap money draws to an end, bondholders are no longer prepared to cut Ghana any slack.

Ghana’s dollar bonds have slumped 10% in 10 days, moving deeper into distressed territory as investors judge that re-financing debt in the Eurobond market won’t be an option when the Federal Reserve hikes rates and budget targets remain elusive.

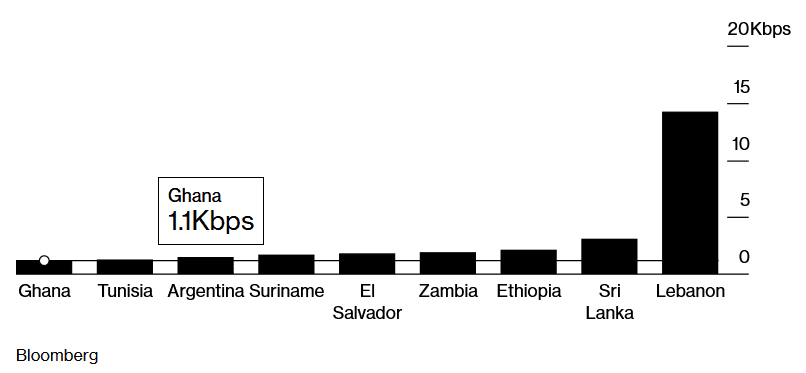

The extra premium demanded on Ghana’s sovereign dollar debt jumped on Wednesday to an average of 1,105 basis points, from 683 basis points in September.

It’s $27 billion of foreign debt had the worst start to the year among emerging markets, extending last year’s 14% loss, according to a Bloomberg index.

Investors are questioning whether Ghana — the region’s second-biggest economy — can sustain its debt levels if a surge in borrowing costs shuts it out of international markets.

Government’s debt climbed to 81.5% of gross domestic product at the end of last year, from 31.4% a decade ago, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

That places Ghana among the most vulnerable credits to tighter U.S. monetary policy, despite strong economic growth.

Welcome to the Club

This month’s selloff places Ghana firmly in EM’s distressed debt nations.

“The market has woken up to the fact that this is a country with a lot of outstanding bonds,” said Kevin Daly, investment director at Aberdeen Standard Investments in London. “A lot of people went into last year with overweight positions and a lot of them have started to throw in the towel.”

The West African nation’s $750 million bonds due in March 2027 fell 10 cents this month to 79.4 cents on the dollar on Thursday, sending the yield to nearly 14%. Of 14 Ghanaian dollar bonds, 13 are trading with an extra premium of at least 1,000 basis points, a level considered distressed, a Bloomberg index tracking sovereign debt showed.

“I don’t expect them to default in 2022, as they have enough foreign-exchange reserves, but medium to longer-term, it becomes an issue as Ghana has lost access to the Eurobond market for rolling over debt,” said Joe Delvaux, a portfolio manager at Amundi in London. “They have too much debt for the size of the economy and investors have lost conviction in the government’s willingness to consolidate spending and take necessary measures.”

The government’s failure to pass a new levy on electronic money transfers through parliament in November also made investors doubt whether it has the political capital to pass revenue-raising measures in parliament or reign in spending to reduce borrowing needs.

The opposition to the tax reform and plans to end a subsidy on pharmaceutical and vehicle imports will make it hard for the government to meet this year’s budget deficit target of 7.4%, down from 12.1% last year.

“There’s no appetite for a new Ghana issuance at this stage and probably won’t be until the government has consolidated its public finances more meaningfully,” said Carlos de Sousa, who helps oversee a $3.8 billion developing nation bond fund at Vontobel Asset Management in Zurich.

— With assistance by Ekow Dontoh