The road to the ring is rarely a straightforward one for boxers, while the path that leads away can often be perilous.

Francis Ampofo is a man who fought his way from the streets of London, where he moved as a child from Ghana, to the top of British boxing in the 1990s – yet the canvas was not to be his only source of glory.

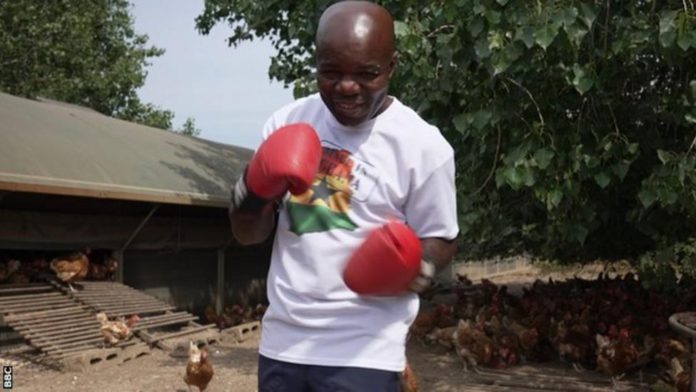

After stepping out of the ring, he took on the world of business in 2003 with the purchase of a 26-acre farm in Norfolk with 10,000 chickens – a nod to his own early life running free in Kumasi.

“I always loved chickens, from back in Ghana,” Ampofo, 55, told BBC Sport Africa.

“As soon as I came here (to the farm), I knew this is it: boxing is over – I want to get into chickens now.”

Twice holding both the British and Commonwealth flyweight titles, Ampofo also challenged for the world title on four occasions – the first coming when losing to South Africa’s “Baby” Jake Matlala for the WBO title at London’s York Hall in 1994.

In a 12-year career, Ampofo won 17 of 28 professional bouts but after retiring in 2002 he returned to something far closer to his heart.

“I was born in Ashtown, Kumasi, which is right in the Ashanti region,” he explained. “I didn’t really know my mum that well, because she came here (to England) when I was three.

“She came to work in the National Health Service and then I was looked after by my grandmother for another three years and that’s where reality started – start working.

“I was selling mangoes, oranges, so she’d peel them all, put them in a bowl that I’d carry on my head and go around selling them, then go back for more.”

Ampofo would work around his schooling in Ghana, where he loved living.

“It was a fantastic time. When I first came to this country, I really, really wanted to go back to Ghana. My mum doesn’t know this but I hated it because it was like prison to me.

“Ghana, from six in the morning, I’m out – nice and sunny – doing what I want, or I go to work in Kumasi market. In this country, it’s different.

“You are locked in all the time, you are inside the house. You don’t go out unless you’re going to school. After school, you’re home. That’s it, there’s no out.”

His sense of boredom was not helped by the fact that he “didn’t know anyone really” in England, a big contrast to his homeland.

“Where we lived (in Ghana), we had about maybe six or seven chickens and they had a little coop where I would go to get all the eggs before giving them to my nan.

“So every morning, that was my job: cleaning chickens, feeding them, giving them water – and all that played a big part in this.

“I think [of] young me and I like animals, birds, chickens, so those early days played a big part in me coming (to the farm).”

Defending himself at school

Ampofo’s early years in London were a challenge despite being reunited with his mother because his diminutive size made him a target at school, unwittingly starting his career.

“I used to fight a lot at school. I’d just come from Africa and couldn’t really take the jokes,” he said. “I needed to defend myself a few times so I joined boxing.

“It was very difficult because then I just couldn’t take the banter of the older boys. I was 13 and must have been under four foot.

“They’d pick me up, chuck me in the bin, put the lid on and I’d get out and start fighting. But they were a bit too strong for me – big lads!

“I thought ‘yeah, one day I will defend myself’ – that’s how it started.

“I loved the training. They’d beat me up and I’d come back and learn more. Eventually, I managed to overcome them and take over.

“I don’t give up easily and I like to win. So I always trained to the top and that got me there.”

Standing at 5’1, Ampofo would go on to be nicknamed “The Pocket Battlerocket” in his professional career.

“I’d do it all over again”

A chance encounter whilst still an amateur nearly saw Ampofo switch allegiances to his country of birth when the Ghanaian boxing team were in London ahead of the 1988 Olympics.

“They came over to England to spar with the GB team and I just happened to be in the GB team as a sparring partner.

“I did ask the Ghana coach if they would take me in to box for Ghana, but they couldn’t as they already had a good flyweight.”

Within a year of his first professional fight in 1990, Ampofo was the British flyweight champion.

Seventeen of his 28 fights would be title contests, with his fourth and final shot at a world title coming in 2002 when Johnny Armour defended his World Boxing Union’s bantamweight title.

Hours later, Ampofo had retired.

“It’s not regret, but I thought I deserved to definitely have one (world title) – I mean, now I can never call myself a former world champion,” he said with a hint of remorse.

Yet over the past 20 years, Ampofo has risen to master another profession, taking great joy in every step of a journey that would have made that little boy in Kumasi in 1970 and his family incredibly proud.

“It’s unbelievable, it’s shocking,” he surmised. “When I got off the plane at Heathrow, I’m a little African kid, I’m just coming to learn car mechanics and go back to Ghana.

“That was my intention, to go back when I was 17 and work but obviously boxing went on, and now I’m here (on the farm). Everything I did in boxing, I absolutely loved it. I’d do it all over again if I got another chance.”