Nigerian star and film director Genevieve Nnaji has already shown that she is a force to be reckoned with, so the disqualification of her Netflix film from the Oscars is unlikely to frustrate her ambitions.

In fact, the rejection of Lionheart earlier this month from the Academy’s best international feature film category may well act as a springboard for her future success.

The 40-year-old has starred in more than 80 films over the last two decades and her rise to prominence coincided with the exponential growth of Nollywood, as the Nigerian film industry is called, across Africa.

Yet she suffered a major setback in 2004 when she was blacklisted by a powerful cartel of film studios in Nigeria, along with several other A-list actors.

READ ALSO:

Nollywood ban

These film studios, operating out of Nigeria’s commercial hub Lagos and Onitsha in the south-east state of Anambra, largely bankrolled Nollywood in the 1990s and early 2000s.

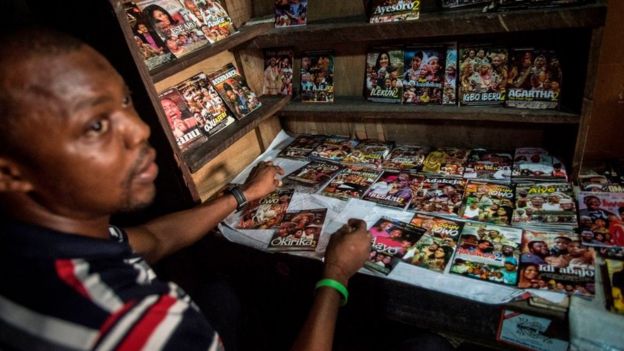

Nollywood is a multi-billion dollar enterprise – and its films are popular across Africa

They gave funds to producers and told them who to hire, says BBC Igbo reporter Vining Ogu, who used to be a film producer based in the southern city of Asaba.

“At some point, the studios felt these A-list stars were collecting too much money and felt they were being held to ransom,” he said.

“At its height, one actor collected 10m naira [$28,000; £21,000] in the early 2000s in cash, which was a lot of money.”

With no producer brave enough to go against the studios, Nnanji found herself out of a job – so she decided to move into music, releasing an album called One Logologo Line.

Her one and only album, it is best remembered for the track No More, a love song with lyrics that could be seen as metaphor for the rest of her career: “No more crying oh, No more fighting oh, No more tears oh, I got my freedom, power and more.”

Screenwriter and director Ishaya Bako traces her rise to the top and the birth of independent producers in Nigeria to that ban.

“The studios thing happening, there was some bad in it, but a lot of good came out of it,” says Bako, who worked with Nnaji on the Road to Yesterday in 2015 – when she made her debut as a producer.

“It made her realise there could be life behind the camera,” he said.

From there as a producer she had more power over what type of films she appeared in and what roles she played.

‘Nigeria’s Sharon Stone’

She started acting as an eight-year-old, starring in the popular TV soap Ripples.

At the start of her career, she brought beauty and adaptability to her roles, now she brings elegance to the screen, says film critic Oris Aigbokhaevbolo

Her Nollywood career really took off when she was 19 in Most Wanted when she played one of four daredevil female armed robbers masquerading as men.

Film director Adim Williams say he takes some credit for “her rise to fame” when he cast her in his 2002 film Sharon Stone – not a biopic of the US actress – in which she played a flirtatious woman.

“In her rising days she was called Sharon Stone and I wrote and directed the movie, which was a massive hit and became sort of her identity,” he said.

He describes Nnaji as “very intelligent” and said she looked like she “was prepared for stardom” the first time he met her.

He says playing “similar characterisations” helped her in the early days, when she was cast as a “likeable, beautiful, loveable girl”.

Perhaps her upbringing had a hand in shaping some of her on-screen roles.

She grew up in the bustling city of Lagos in a middle-class home – her father an engineer and her mother a teacher.

Actor Richard Mofe Damijo, who has co-starred with her several times, says she is a natural on screen.

“She was and still is one of our queens and she always comes to the party with a winning spirit,” he told the BBC.

In 2011 she was honoured with an award by the Nigerian government for her contributions to the film industry – yet she was not done, wanting to try her hand at directing.

Could Netflix help with standards?

When in 2018 Netflix announced that it was acquiring the rights to Lionheart, her directorial debut, it was seen as a massive boost for Nigeria’s film industry.

Nollywood is a multi-billion dollar enterprise but with short turn-around times, not much attention is paid to technical details and storytelling.

With an average production budget of between $15,000 and $70,000, most films are shot within a month and expected to be profitable.

Kenneth Gyang, an independent producer based in the northern city of Jos, said Nnaji’s deal with Netflix “has opened up the possibility that money can be sourced from other avenues”.

“Netflix has quality control that is very high. Now they [producers] know that if it is a very good film they can sell it as an original and make more money,” he told the BBC.

Film critic Oris Aigbokhaevbolo agrees that the Netflix deal showed other filmmakers that good films could be profitable.

Actor Nkem Owoh is popular for his comedies but kept a straight face when he starred alongside Nnaji in Lionheart

When Lionheart was nominated for the Oscars, Nnaji described it as a “pivotal moment in the history of Nigerian cinema”.

However, films in the best international feature film category must have “a predominantly non-English dialogue track”.

Lionheart, in which Nnaji also stars, is largely in English, with an 11-minute section in Igbo – hence its rejection.

Nnaji hit out at the Academy, tweeting: “We did not choose who colonised us.”

But the rules were clear and the Nigerian selection committee had bungled it.

Yet some feel it may be a watershed moment for more local-language films to be produced.

“Nollywood has proven itself stubborn to change. Perhaps Genevieve and the rest will spearhead it,” says Mr Aigbokhaevbolo.

So it may be that this rejection could open another chapter for the director and Nollywood.