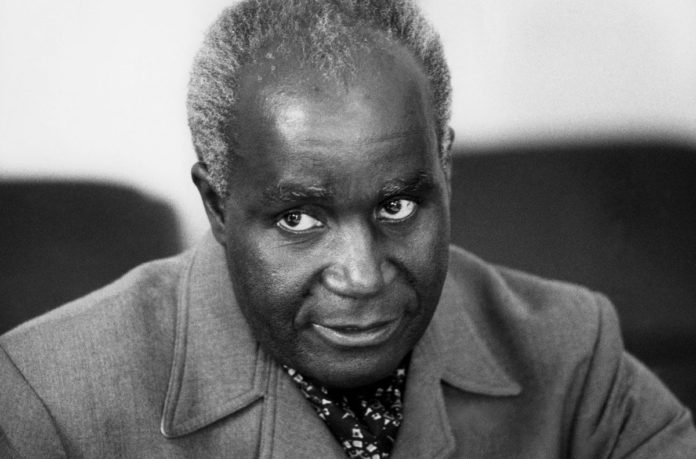

Kenneth Kaunda, who led Zambia to independence and then served as the nation’s president for almost three decades, has died.

He was 97.

Kaunda’s death was announced by Simon Miti, the cabinet secretary, in a televised speech and President Edgar Lungu declared 21 days of national mourning for the former leader.

While Kaunda had been admitted to the Maina Soko Military Hospital, the main government treatment center for Covid-19 patients, on June 14, he tested negative for the virus and was suffering from pneumonia, according to media reports that cited his assistant.

Waving his trademark white handkerchief to signal approval to crowds of supporters or to dismiss a journalist’s question, Kaunda emerged as a major figure in the fight for majority rule across southern Africa.

His government provided support to Black liberation movements in neighboring Zimbabwe, Namibia, Angola and Mozambique, and he was an outspoken critic of South Africa’s White-minority government.

The son of a missionary and the youngest of eight children, Kaunda left teaching in 1954 to lead a civil disobedience campaign, known as Cha-Cha-Cha, against British rule in its Northern Rhodesia colony.

He was jailed twice, for two months in 1955 and nine months in 1959. When Zambia gained independence in 1964, Kaunda, known as KK, was appointed president.

Kaunda, born on April 28, 1924, outlived Nelson Mandela and Robert Mugabe, fellow giants of southern Africa’s liberation struggles. South Africa carried out military attacks in Zambia in the 1980s, as Kaunda supported efforts to topple the apartheid government.

In 1972, Kaunda declared his United National Independence Party as Zambia’s sole legal party and said it was founded on principles he alternately called Zambian humanism and African socialism.

His government maintained a state of emergency for almost all his 27 years in power.

Mine Nationalization

By 1973, Kaunda nationalized the nation’s copper mines, which had been developed by companies including what’s now known as Anglo American Plc, and were Zambia’s main source of income.

The decision coincided with a global energy crisis and a slump in copper prices that caused debt to spiral. Production collapsed from 750,000 metric tons that year to 257,000 tons by 2000.

Kaunda pioneered ties with Mao Zedong’s China in 1967. Facing a crisis as tensions cut trade from South Africa and the then self-declared independent Rhodesia to the south, Kaunda secured what was then the biggest Chinese aid project globally: a 1,870-kilometer (1,162 miles) railway line connecting the country to Tanzania’s Dar es Salaam port to the east.

China is now Zambia’s biggest sovereign creditor, accounting for more than one quarter of its total external public debt.

Economic and political pressure forced Kaunda to yield to free elections in 1991, which he lost to the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy led by Frederick Chiluba, who won 81% of the vote.

Kaunda accepted the result, becoming only the second leader in sub-Saharan Africa, after Mathieu Kerekou of Benin, to allow a multiparty vote and leave power peacefully when he lost.

Chiluba failed in his attempt to deport Kaunda on the grounds that his father was Malawian and thus wasn’t a “true Zambian.” Kaunda retired to a modest house in the capital, Lusaka, where he would often personally make tea and play his guitar for visitors.

Kaunda’s wife, Betty, died in 2012. The couple had eight children, according to the state-owned Times of Zambia.