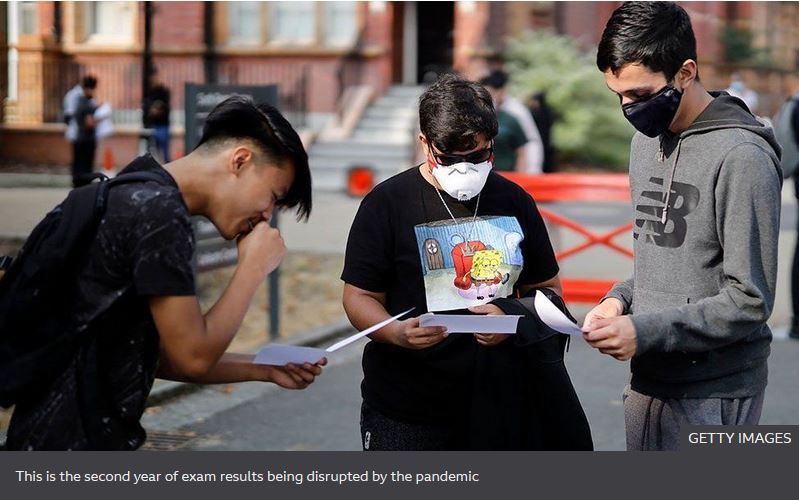

GCSEs and A-levels cancelled in England by the pandemic will be replaced by grades decided by teachers, the exams watchdog Ofqual has confirmed.

Schools can determine grades this summer by using a combination of mock exams, coursework and essays.

There will be optional assessments set by exam boards for all subjects, but they will not be taken in exam conditions nor decide final grades.

Results will be published earlier in August to allow time to appeal.

I’m not a member of Association of African Albinos – Foh-Amoaning reacts

The new arrangements, which will be set out by the education secretary in the House of Commons later, come after a consultation into how best to assess pupils after months of school and college closures.

Last summer, thousands of A-level students had their results downgraded from school estimates by a controversial algorithm, before Ofqual announced a U-turn which allowed them to use teachers’ predictions instead.

There will be no fixed share of grades and schools will not be expected to keep in line with last year’s results or any earlier year.

But the Education Policy Institute think tank has warned the plans for this year risk “extremely high grade inflation”.

How will the grading system work?

After last year’s chaos, the exams watchdog Ofqual and the Department for Education say there will be no algorithm calculating results.

Instead, the grading system will be built around teachers’ judgements – with schools allowed to decide on the evidence to be used, such as mock exams, coursework and essays.

Education Secretary Gavin Williamson said it was the “fairest possible system” to ask “those who know them best, their teachers, to determine their grades”.

He told a Downing Street press briefing on Wednesday there would be “a very clear and robust appeals mechanism”.

If students are unhappy at the outcome of what their school and teachers have decided, they can appeal, with no financial charge expected.

For those still wanting to take written papers, there will be an option of exams in the autumn.

A-level results day will be 10 August, with GCSEs results given out on 12 August.

They are earlier this year to create a “buffer” for appeals, ahead of decisions over university places in the autumn.

Before the end of the school year, teachers can tell pupils how they got on in the test papers set by exam boards – but not their final grades.

Will students still have to sit exams?

There will be test papers set by exam boards for each subject, which are intended to inform the judgement of teachers, but will not decide the final grades.

These have been labelled “mini-exams”, but Ofqual says the tests, which will be optional for schools to use, should not be seen as exams.

Question papers, which could be from previous exams, will be sent to schools before the Easter holidays and can be taken before 18 June, when schools have to submit grades to exam boards.

The intention is that regardless of how much time pupils might have missed out of school, they will have questions on a topic they will have studied.

These tests will be taken in class rather than exam halls, there is no fixed time limit for their duration and they will be marked by teachers.

What checks are in place?

There will be no fixed share of grades – and schools will not be expected to keep in line with last year’s results or any earlier year.

Instead teachers will be expected to award grades based on their professional judgement, drawing on whatever evidence is available.

Schools will be given detailed information about grading and will be expected to ensure consistency between teachers.

Exam boards will check random samples and if there are specific concerns about unusual results, they can investigate and change grades.

What about vocational exams?

Teachers’ grades will be used to replace written vocational exams, in the same way as GCSEs and A-levels.

But where there are practical, hands-on skills to be tested, such as for a professional qualification, some of these exams will continue in a Covid-safe way.

What do students think about it?

Caitlyn in Wigan, aged 15, is taking nine GCSEs and has been studying at home where it’s hard to concentrate and the wi-fi keeps crashing. She is glad she won’t have to sit exams.

“You feel relief because there’s not so much pressure,” she says, especially when they had missed so much time in school.

“It’s not the same as face-to face interactions with teachers,” she says.

The mock exams she sat in November she found particularly hard. “You had that fear of going into a hall with 200 people around you.

“It was really stressful as obviously, we’d been online learning so then you had to quickly cram everything in which made quite a few people drained.”

Kori from Blackburn, aged 16, is taking five GCSES.

He says learning from home was “in a way better for me, so I could concentrate and there was no-one to distract me”. Although he did miss the support of teachers when he got stuck.

Kori feels the assessments, the so-called “mini exams”, that will be offered “are going to be better for me”.

Although he worries all the pupils this year might be judged unfairly because they didn’t sit the full exams.

What’s the reaction?

The Education Policy Institute warned of a “high risk of inconsistencies” between schools – and if there are large numbers of successful appeals or widespread grade inflation it could be difficult for universities and employers to distinguish between applicants.

But the ASCL head teachers’ union supported giving schools “flexibility over the assessments they use”. While the National Education Union said it was probably the “least worst option available”.

Parenting charity Parentkind said “teacher assessment is, under the circumstances, the fairest way to test pupils”.

Labour’s Shadow Education Secretary Kate Green said delays to deciding a replacement for exams had “created needless stress for pupils, parents and teachers”.