For months, Tanzania’s government has insisted the country was free from Covid-19 – so there are no plans for vaccination.

The BBC’s Dickens Olewe has spoken to one family mourning the death of a husband and father suspected of having had the disease. The fear is that amid the denial, there are many more unacknowledged victims of this highly contagious virus.

A week after Peter – not his real name – arrived home from work with a dry cough and loss of taste, he was taken to hospital, where he died within hours. He had not been tested for Covid. But then, according to Tanzania’s government, which has not published data on the coronavirus for months, the country is “Covid-19-free”.

There is little testing and no plans for a vaccination programme in the East African country.

It is nearly impossible to gauge the true extent of the virus and only a small number of people are officially allowed to talk about the issue.

Recent public statements have hinted at a different reality at a time when some citizens, like Peter’s wife, are quietly mourning the deaths of family members suspected to have had the virus.

Several Tanzanian families have had similar experiences but have chosen not to speak out, fearing retribution from the government.

The British government has banned all travellers arriving from Tanzania, while the US has warned against going to the country because of coronavirus.

Vaccine dispute

Since June last year, when President John Magufuli declared the country “Covid-19 free”, he, along with other top government officials, have mocked the efficacy of masks, doubted if testing works, and teased neighbouring countries which have imposed health measures to curb the virus.

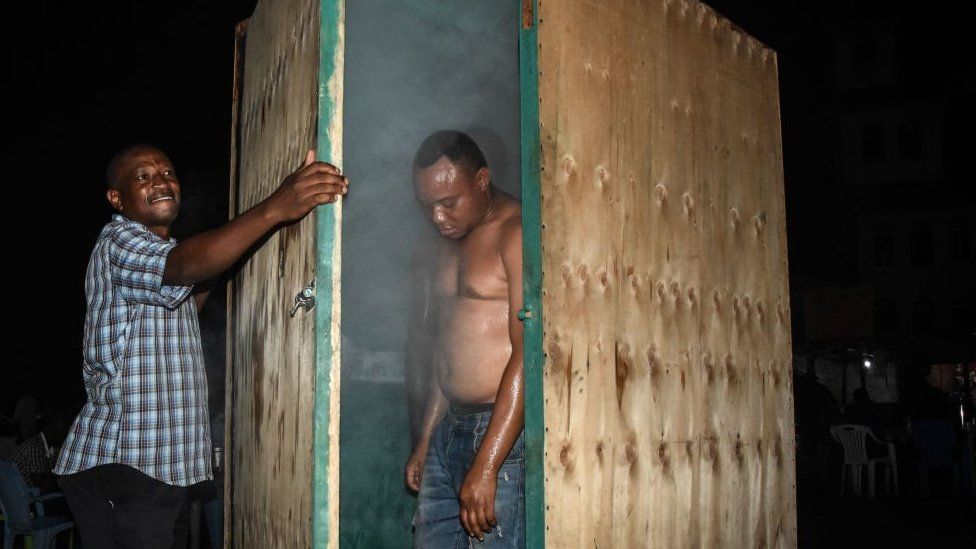

Mr Magufuli has also warned – without providing any evidence – that Covid-19 vaccines could be harmful and has instead been urging Tanzanians to use steam inhalation and herbal medicines, neither of which have been approved by the World Health Organization (WHO) as treatments.

It is unclear why the president has expressed such scepticism about the vaccines but he recently said that Tanzanians should not be used as “guinea pigs”.

“If the white man was able to come up with vaccinations, he should have found a vaccination for Aids, cancer and TB by now,” said Mr Magufuli, who has often cast himself as standing up to Western imperialism.

The WHO disagrees.

“Vaccines work and I encourage the [Tanzanian] government to prepare for a Covid vaccination campaign,” said Dr Matshidiso Moeti, the WHO’s Africa director, adding that the organisation was ready to support the country.

But Health Minister, Dorothy Gwajima, reiterated Mr Magufuli’s stance on vaccines, adding that the ministry had “its own procedure on how to receive medicines and we do so after we have satisfied ourselves with the product.”

She made the comments at a press briefing this week at which an official demonstrated how to make a smoothie using ginger, onions, lemons and pepper – a drink, they said without providing evidence, which would help prevent catching coronavirus.

“We must improve our personal hygiene, wash hands with running water and soap, use handkerchiefs, herbal steam, exercise, eat nutritious food, drink plenty of water, and [use] natural remedies that our nation is endowed with,” Dr Gwajima said.

But this was not because the virus was in the country. Tanzanians had to be prepared because the virus was “ravaging” neighbouring countries, she said.

Some medics are sceptical about the government’s stance.

“The problem here is the government is telling Tanzanians that the vegetable mixture, which has nutritional benefits, is all they need to keep coronavirus at bay, which is not the case,” a local doctor, speaking anonymously, told the BBC, adding that people still had to take precautions against the virus.

Dr Gwajima, the president, and three other top officials are the only ones who can give information about Covid-19 in the country, according to a directive from Mr Magufuli.

But in an unpreceded move, leaders of the Catholic church in the country broke their silence recently and warned the public to observe health measures to curb the spread of the virus.

“Covid is not finished, Covid is still here. Let’s not be reckless, we need to protect ourselves, wash your hands with soap and water. We also have to go back to wearing masks,” said Bishop of Dar es Salaam Yuda Thadei Ruwaichi.

The secretary of the Tanzania Episcopal Conference, Father Charles Kitima, told BBC Swahili that the church had noticed a rise in funeral services in urban areas.

“We were used to having one or two requiem masses per week in urban parishes, but now we have daily masses. Something is definitely amiss,” he said.

The health minister said that the statements were alarmist. The lack of official data makes it hard to have an informed public discussion.

‘Wear masks – not because of corona’

But the government is not in total denial as there have been moments when it appears to acknowledge the virus might exist in the country.

In January, days after Denmark reported that two of its citizens who had visited Tanzania had tested positive for the more transmissible South African variant of the virus, Mr Magufuli blamed Tanzanians who travel abroad for “importing a new weird corona”.

After visiting two hospitals, Prof Mabula Mchembe, the permanent secretary in the health ministry, said that patients with respiratory problems were suffering from hypertension, kidney failure or asthma rather than coronavirus.

But a later statement on the health ministry’s Twitter account that “not all patients admitted to the hospital have corona”, implied that there were some who had the virus.

On Friday it was reported on the Mwananchi news site that Prof Mchembe encouraged people to wear masks “not because of corona, like some people think, but it’s to prevent respiratory diseases”.

One development that has complicated the government’s position is the public announcement by opposition party ACT Wazalendo that one of its top officials, Seif Sharif Hamad, and his wife, had tested positive for the virus.

The government has not publicly commented on Mr Hamad’s condition, neither has it responded to repeated BBC requests for comment for this article.

On 21 January, the day Peter started feeling unwell, Tanzanians were gripped by a story from the north-western town of Moshi.

The administrators of a well-known international school had retracted a statement and apologised for announcing that the school would stop offering in-person learning for one of its year groups after a student had tested positive for coronavirus.

The retraction came after the management met government authorities in the region, The Citizen news site reported.

The school said it regretted the “circulation of the false information” and would continue with normal operations.

This sense of carrying on as if nothing had happened is what the government has been encouraging, but Peter’s wife is gripped by regret, because like other Tanzanians she and her late husband took no precautions to protect themselves.

Their lack of caution was perhaps not surprising given that the president and other top government officials have continually stressed “there’s no corona”.