Ana* was 18 years old when she found out about surrogacy from a television news report.

She had just finished secondary school and had plans to work in a hotel in her small western Ukrainian town, where tourists come to see a medieval castle.

That job pays $200 a month, but for carrying someone else’s baby, she learned, she could earn up to $20,000 (£14,000).

Ana’s family is not poor by local standards. Her mother is an accountant and has always supported her.

But she says she was drawn to surrogacy because she “wanted to have something more”, to be able to afford “expensive things” – house renovations, a car, appliances.

Ana stirs her latte nervously as she talks. Although hundreds of women are doing it, surrogacy is still not talked about openly in Ukraine.

Foreign couples have been coming to this corner of Europe in droves since 2015, when surrogacy hotspots in Asia began closing their industries one-by-one, amid reports of exploitation. Barred from India, Nepal and Thailand, they turned to Ukraine, one of the few places left where surrogacy can still be arranged at a fraction of what it costs in the US.

“We have so many childless couples coming to our country – it’s like a conveyor belt,” says Ana, who asked for her identity to be protected.

When she was 21, and after some years of hotel work, Ana finally decided to become a surrogate. By then she had a daughter and realised she was eligible. Under Ukrainian law, a surrogate must have a child of their own before carrying someone else’s. If you have your own child, you are less likely to become attached to the one you must give away, those who recruit the women say.

– Ana hopes buy a flat for her daughter in her hometown, Kamyanets-Podilskyi

A long journey

Ana began trawling the websites where surrogates, agents, clinics and assorted middlemen post advertisements.

Soon she was 450km (280 miles) away, in the capital Kiev, for health checks. She signed a contract with a couple from Slovenia unable to have their own child. Ana was lucky – an embryo implanted in her uterus the first time she underwent the taxing transfer process.

But it was then that the difficulties started. She says the quality of care provided by the clinic went downhill quickly. Some surrogates had health problems that were not diagnosed correctly or treated on time, leading to complications, she says.

She posted her complaints online to warn other women but was rebuked by the clinic and remains too nervous to name them publicly.

The baby she delivered was born healthy but the experience left Ana wary. Still, she has now agreed to be a surrogate again, this time for a Japanese couple. They are handling things through a lawyer in Kiev and she will likely never meet them in person.

Ana has been more prudent in her choice of clinic this time around, but if all goes to plan, by the age of 24 she will have given birth to three children – one of her own, and two for someone else.

Europe’s capital of surrogacy

Demand for surrogacy in Ukraine “has increased probably 1000% in the last two years alone,” says Sam Everingham of Families Through Surrogacy, a Sydney-based charity that advises would-be parents.

The country, he adds, “has found itself almost accidentally as one of the handful of nation states” which allow surrogacy tourism.

Apart from the simple fact that it is legal, Ukraine’s liberal laws attract people. It recognises the “intending parents” as the biological parents from the moment of conception and places no limit on how much a surrogate may be paid – essentially creating an open market where women can demand their chosen price.

But that does not mean it is straightforward. Depending where you come from, the process of actually getting the baby out of Ukraine can be a bureaucratic nightmare, with couples from some countries, including the UK, needing to stay there for many months.

– Clinics like the Ilaya medical centre in Kiev draw clients from all over the world

While many clinics in Ukraine appear to be operating transparently and treating the women well, industry insiders and surrogates will whisper about those with bad reputations. There are unverified stories of embryos being secretly swapped, poor health screenings and operators taking on too many clients to be able to offer the adequate level of care.

“We have seen examples where Ukrainian agencies have refused to pay the surrogate if she doesn’t adhere to strict requirements, if she miscarries,” says Mr Everingham. “There are some awful examples where agencies really treated surrogates dreadfully in Ukraine if things haven’t worked out to the benefit of parents.”

– Surrogates travel to Kiev from their hometowns for regular check-ups

Olga Bogomolets, a doctor and MP who chairs Ukraine’s parliamentary committee on health, said she believed young women were being drawn into surrogacy “as a result of the rapid fall in living standards” in the country. The economy was hit by a deep recession in 2014 and 2015, in part because of the ongoing conflict in eastern Ukraine between the military and Russia-backed separatists.

The industry, Ms Bogomolets says, is not sufficiently regulated and this lack of oversight can put both surrogate mothers and the paying parents at risk.

The Ukrainian health ministry has not responded to requests for comment.

How does surrogacy in Ukraine work?

- Available to heterosexual, married couples able to prove they cannot carry a baby themselves for medical reasons

- At least one parent must have a genetic link to the baby; egg donors are frequently used

- Costs vary, but range from $30,000-$45,000 on average

- The paying parents are on the Ukrainian birth certificate; the surrogate has no legal right to claim custody of the baby

- It is estimated about 500 surrogacies may be happening every year but there is a lack of available data

- Commercial surrogacy of this kind is legal in the US, Georgia and Russia. Kenya and Laos are also destinations but have no laws in place

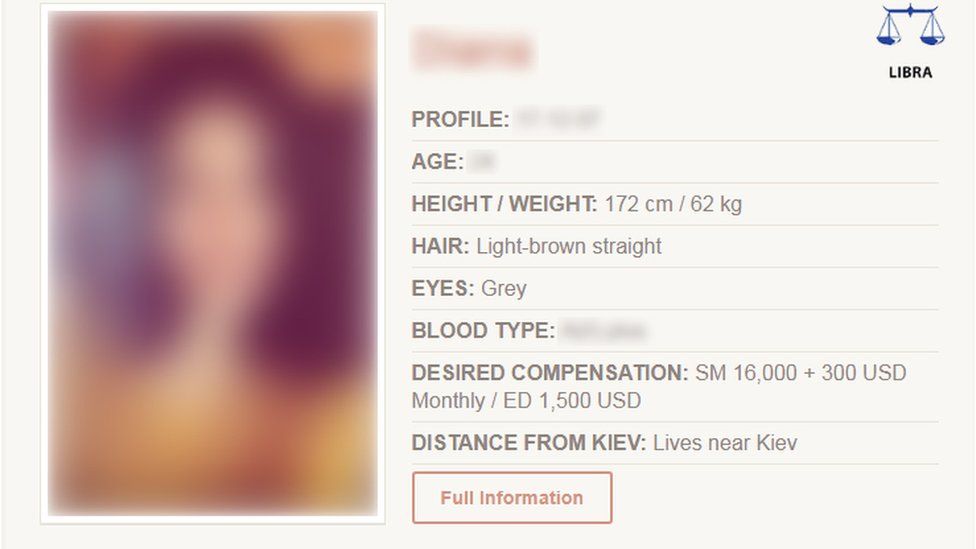

– There are hundreds of listings like this on surrogacy agency websites

For Mark, who travelled with his wife from Ireland to Ukraine for surrogacy in late 2015, the choice of agency and clinic was crucial.

His experience was overwhelmingly positive. His son was born in 2016 after IVF using his sperm and a donor egg, and he says the healthcare was as good as anywhere in Western Europe.

They had a warm relationship with the 32-year-old surrogate – who they paid directly – and his wife was invited into the room during the birth.

“At no point, from the clinic or the maternity house, did we get the feeling [the surrogate] was treated as a second-class citizen,” says Mark.

“We knew why she was doing this,” he adds. “She had a daughter – she got pregnant when she was 15. She wanted to send her to college and have an opportunity she could never have.”

– Mark’s son was born in 2016. Going to Ukraine was the “most important thing” he has ever done

‘You feel the baby kicking’

For a couple sitting in London, Dublin or Shanghai, the decision to go ahead with surrogacy in Ukraine is fraught with uncertainty. Parents rely on online forums to find out which clinics have the best reputations, and trade stories – both good and bad – about their experiences.

But at least one clinic is known to pay disgruntled parents “significant sums to write glowing reviews”, says Mr Everingham, making it even harder for people to know who to trust.

The Ilaya medical centre in Kiev, from all appearances, is not the kind of clinic that would need to do that. It says its “very good reputation” attracts a waiting list of surrogates.

In a waiting room at the gleaming facility, two women from the east of the country discuss their pregnancies.

Tetiana, a red-haired mother of three, is 30 weeks pregnant with a baby for a Spanish couple.

“You feel the baby kicking, and you are talking to him,” she says of the experience of carrying someone else’s child. “But subconsciously, you realise it’s not yours.”

Tetiana lives with her mother but has hidden the pregnancy from her, saying she wanted to move to Kiev to look for work.

Tetiana lives with her mother but has hidden the pregnancy from her, saying she wanted to move to Kiev to look for work.

Jana, who gave birth two months ago, advises Tetiana that she must see the surrogacy as just a job. She remembers the child she carried being taken away almost immediately after the birth, as she lay exhausted in her hospital bed.

She admits that maternal feelings lingered, and she thought about the child after she returned home.

“You would have to be a cold person not to feel this,” she says.

“But when you see the joy and smiles of the biological parents, that’s it. You realise everything is okay with the child and the parents are happy.”

Back at home with her own daughter in western Ukraine, Ana is also thinking about her role as a surrogate.

Soon, she will take a seven-hour train to Kiev for an embryo transfer attempt for the new Japanese couple.

Although it can be one of the hardest parts of the process, she is in an upbeat mood about what awaits her. She hopes she can use the money to buy her own flat.

But Ana is also proud of what she can do for the paying parents.

“When they are crying and thanking you, you feel how much you have done for them,” she says. “[They] told me that I was the most important person in their lives.”