Bonheur Malenga, a Congolese university student, found himself facing a dilemma one day last month about whether to purchase online data.

“As I was hungry, I didn’t know if I should buy food or get a 24-hour internet bundle,” he told the BBC.

The 27-year-old, who is studying engineering, relies on his parents for financial support – but has been spending more than usual as he has been doing research online for his final-year dissertation.

He lives in Kinshasa, capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, where 26% of average income to spent getting online using mobiles – the easiest way to access the internet here.

“I told myself that staying hungry for a day and a night wouldn’t kill me. So, I just bought the internet bundle and slept on an empty stomach,” he said.

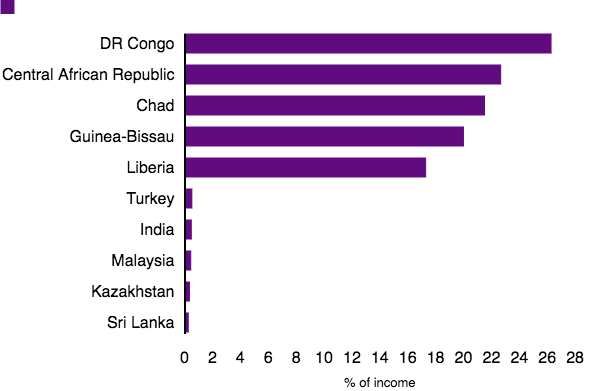

Cost of 1GB of mobile broadband data

Top five and bottom five countries

100 low- and middle-income countries included in the survey. Source: A4AI

Mr Malenga says many of his friends face the same dilemma.

DR Congo is classed as the most expensive country to get online in the world, according to the 2019 Affordability Report from the Alliance for Affordable Internet.

The organisation determines affordable internet as paying 2% or less of your average monthly income for 1GB of mobile broadband data.

‘The cybercafé boss took my shoes’

On the other side of the country, more than 2,000km (about 1,240 miles) east of Kinshasa, Eric Kasinga remembers an embarrassing moment that happened to him a few years ago.

Like many young people living in the town of Bukavu, he had to go to a cybercafé to get online. He was applying for a postgraduate course at a reputable university in The Netherlands.

“The internet was so slow that the whole application process ended up taking three hours instead of one,” he says.

But he only had enough money to pay for an hour.

He explained the situation to the cybercafé manager, hoping he would be allowed to bring the money later.

However, the manager started shouting curses at him, screaming: “The internet is not for poor people.”

For payment, the manager pulled off the new shoes Mr Kasinga was wearing, forcing him to walk the long distance home barefoot.

“I felt terribly ashamed,” he says.

The graduate, who now works for a conservation organisation, was never able to follow up on his university application. He did try to get his shoes back later that week, but the cybercafé manager had already sold them.

“Nobody should have to experience this just for internet,” he says.

Access to the internet was recognised by the UN as a human right in July 2016

DR Congo is the fourth-most populated country in Africa, two-thirds the size of western Europe and is rich in the minerals used to make smartphones.

Yet many of its citizens have a hard time accessing basic services such as proper healthcare, drinking water and electricity.

For them, accessing the internet, recognised by the UN as a human right in July 2016, is regarded as a luxury.

The Congolese Post and Telecommunications Regulation Authority (ARPTC) estimates that only 17% of population has online access.

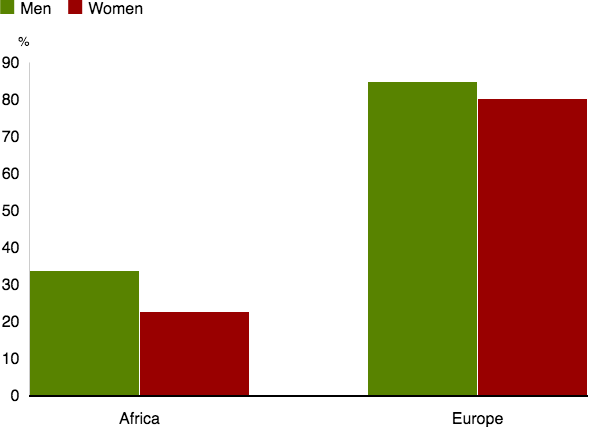

Another recent report also points the growing digital gender gap. More than 33.8% of men compared to 22.6% of women in Africa have online access, the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) said.

Internet gender gap

Africa and Europe

Percentage of men/women who use the internet on those continents. Source: ITU

Kodjo Ndukuma, an expert on digital rights at Kinshasa’s Université Pédagogique Nationale (UPN), says there are three main reasons for the high costs of the internet.

1. Nobody knows exactly how much it should cost

“The modelling of cost is done when you make calculations based on investments put in by a telecom company, the running cost and the number of subscribers,” he says.

These calculations have been made for voice calls but no telecommunication company has done that for internet data, meaning the regulator cannot put a cap on prices.

“The lack of a clear ceiling gives companies freedom to fix whatever price they want,” says Prof Kojdo.

2. A lack of competition

The number of subscribers and the number of telecom firms has remained stagnant for many years – limiting competition.

“All it takes is for this small number of companies to agree on one thing and nobody can stop them,” says Prof Kojdo.

He gave the example of April 2016 when all the Congolese telecommunication companies, bar one, agreed to increase the price of mobile data by 500%.

3. Over taxation

“Telecommunication companies pay taxes on the national, provincial and sometimes local levels,” says the professor.

“They just put it on the heads of subscribers.”

The government is facing pressure to intervene, following protests by a youth movement known as La Lucha.

Between March and October, the group, acting as a de facto consumer rights organisation, held 11 demonstrations across the country calling for internet data costs to be lowered.

“The regulatory authority told us in a meeting that there are legal limits as to how far they can interfere in the operations of telecom companies,” said Bienvenu Matumo from La Lucha.

“Still, we want the government to do something instead of watching us being scammed.”

The information technology minister was the one who called on the regulator, La Lucha and the telecoms firms to meet and thrash out a solution – the government itself is not allowed by law to interfere.

But the first meeting failed to come up with concrete steps to reduce the costs or improve the quality of internet services.

‘Fear of eating data’

For businesswoman Vanessa Baya any improvement on the current situation cannot come too soon.

She runs a marketing business and relies on the internet to reach her clients.

“The quality of the internet network is so unreliable that I have to switch between more than two different telecom operators in a single day,” she says.

That means buying extra data bundles for each operator, sacrificing other needs. But this does not solve her problems as she is not able to shoulder the cost of her customers.

“Even if I get online and share the catalogue of products with clients, they rarely download it, fearing it may eat up all their data.”