Preliminary data gathered by researchers shows that commuters are unknowingly breathing in toxic air during rush hours.

As they navigate the daily grind, crowding into public transport vehicles and inching through traffic, they are exposed to harmful pollutants.

Air pollution is now the second leading global risk factor for death. This shocking data comes from a UNICEF-backed report, in collaboration with the Health Effects Institute.

The numbers reveal a grim reality: in 2021, air pollution killed 8.1 million people, translating to about 22,192 deaths every day. Even more heartbreaking, one child dies every minute due to air pollution.

“The statistics are stark. The last report on the state of the air showed that there were a little over seven million deaths due to air pollution-related diseases,” remarked Desmond Appiah, country lead of the Clean Air Fund.

The biggest culprit is Ghana’s ageing, highly polluting fleet of vehicles. A sea of cars crawls bumper to bumper, thickening the air with harmful particles and gases. It’s rush hour, a bustling time when everyone is on the move, crowding into public transport vehicles to reach their destinations.

For those navigating this daily ordeal, the respiratory strain is palpable, with each breath laden with potential health risks.

“It’s not easy. It’s a difficult moment, especially something that relates to your breath. You can’t breathe as you do so often. It’s challenging breathing, especially at night when you’re asleep,” said Reuben Alexander Otu.

Reuben Alexander Otu has asthma, a life-threatening illness that constricts airways. He’s one of a growing number of Ghanaians with respiratory illnesses and a range of ailments, including heart conditions that doctors say are worsened by toxic air. He thinks all day, every day, about avoiding triggers.

“You encounter different kinds of cars with smoke from their exhaust pipes, very bad and they’re not the best. It will help me to at least have a clean breath of air, so that’s why I normally put on my nose mask, especially when I use the trotro and stuff, people might come in with all sorts of perfumes which may not be best for me,” said Reuben Alexander Otu.

70% of daily commuters in Ghana use privately run minibuses known as ‘Trotros’, which are often older, higher-emitting vehicles. Researchers at Afri-SET, an air quality research organisation, are studying commuter exposure during rush hours using wearable mobile sensors. The preliminary results, according to James Nimo, a research associate at Afri-SET, are startling.

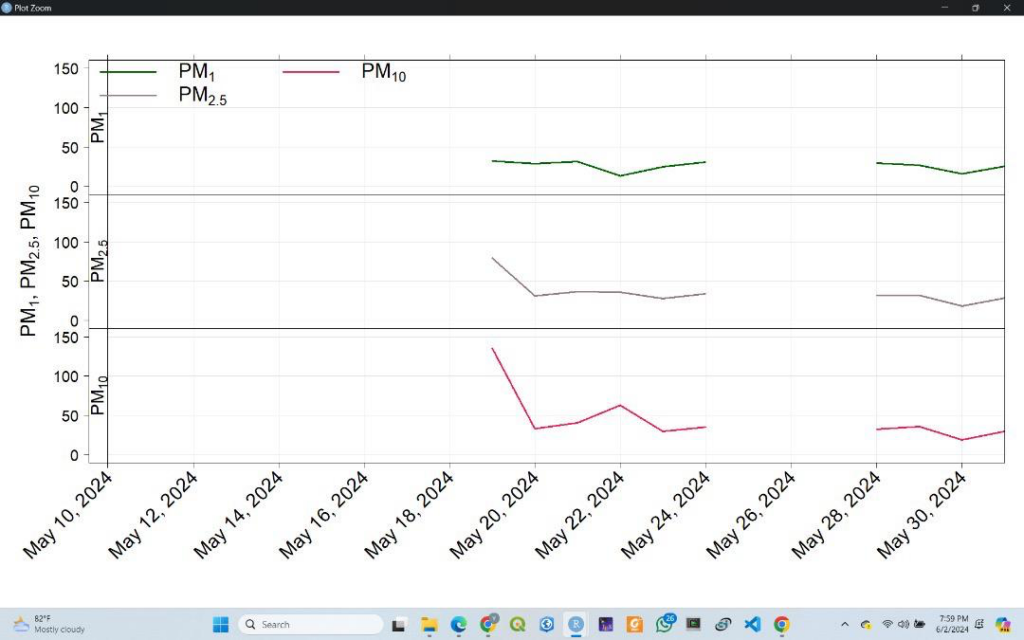

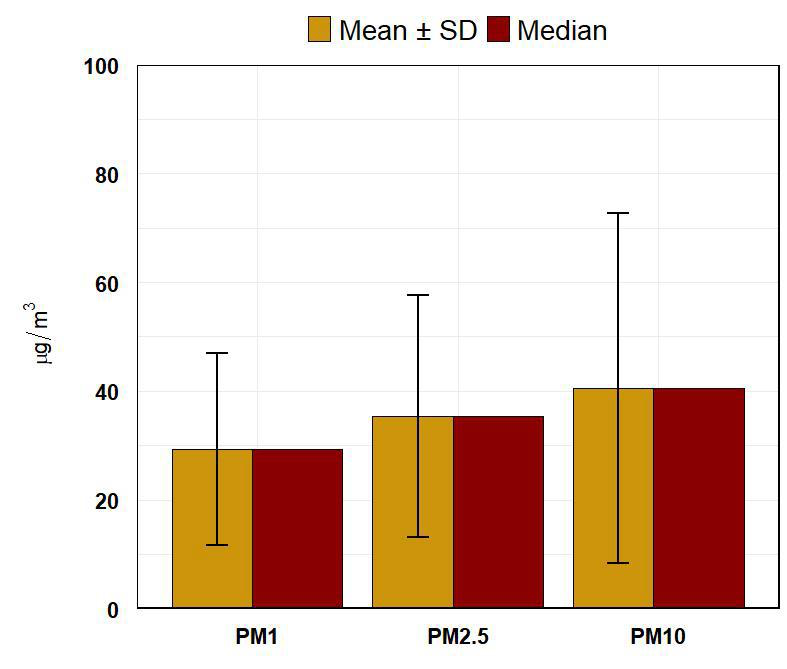

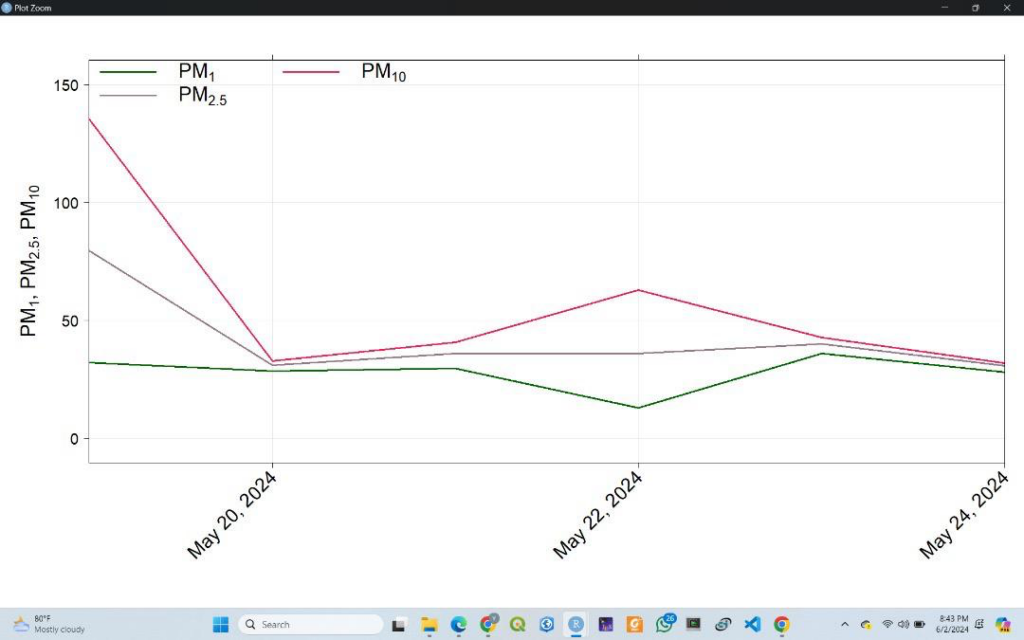

“We give it to them to wear. The idea is to wear the device close to their nose level, just to see whether what they are breathing in will be the same as the sensor is picking. So, the uncalibrated data shows that rush hours are around 80 milligrams per cubic meter, which is not good for human health. So from that graph, you could see that between six and 10, we have some peaks,” said James Nimo.

The transport sector, made up of 3.2 million vehicles as of 2022, is the leading producer of air pollution. Pollutants from the transport sector account for nearly 40% of the country’s air pollution, dwarfing the contributions from industries at 11% and households at 10%.

Chief reporter at Ghana News Agency, Edward Acquah, was among the few volunteers on the project, documenting his daily commute from Abelemkpe to Accra Central. According to sensor data, pollution levels ranged from “moderate” to “unhealthy for sensitive groups” on average.

However, during several segments of the trip, the pollution spiked to “severely polluted,” posing risks even to healthy individuals.

“I do not get a straight car to work and I don’t have a car at the moment. What I do is that I join one car to Kaneshie, and then from there, I join another vehicle to Tema Station. Then just a walking distance to my office.”

Edward admits to feeling a deep sense of helplessness after witnessing these alarming results firsthand.

“It appears that apart from you protecting yourself personally by way of a nose mask, you cannot do anything much to stop the pollution because it’s your natural environment, your natural routine. It’s very disturbing because it’s a daily thing and you cannot go without it.”

The WHO estimates 28,000 people die prematurely every year in Ghana as a result of air pollution. Between 2020 and 2023, the Ghana Health Service’s Non-Communicable Disease (NCD) Control Programme documented over 230,000 new cases of asthma.

An epidemiologist at the University of Ghana, Dr Reginald Quansah, knows why.

“Air pollution levels are consistently moving up. Several factors account for this. I think one of the things that is very obvious is emissions from vehicles,” he said.

The good news is that there are things people can do to reduce their exposure. Dr. Carl Osei says the easiest is to wear a good mask.

“Within the limitations of some of these protective masks like the respirators, you can reduce the black carbons and the particulates and reduce your exposure.”

Desmond Appiah, Country Lead of the Clean Air Fund, insists that enforcing air pollution laws is essential to protect ordinary Ghanaians.

“There’s a lot more that we need to be doing to be able to push the needle. The challenge that the clean air field faces is that the quality of the air is not seen, so we call it a silent killer. We are breathing, but we may not see that this is the state of the quality.”

Afri-SET, led by Dr. Allison Felix Hughes, plans to conduct extensive research across diverse socioeconomic backgrounds and geographic locations to identify environmental hotspots nationwide.

“Looking at the future, what we intend to do is to do a more detailed study. I mean, market women and different groups, how the level of exposure is to these various groups. It is aimed at strengthening air quality laws.”

The EPA and other government agencies, including members of parliament, are actively exploring various regulations aimed at strengthening air quality laws.

ALSO READ:

- Ofankor-Nsawam road project: Residents struggle with air pollution

-

Road toll collectors at great risk of diseases caused by air pollution

This story was a collaboration with New Narratives. Funding was provided by the Clean Air Fund, which had no say in the story’s content.