About 700 metres (765 yards) from Ghana’s Parliament sits one of the world’s most controversial craters, a hole surrounded by weeds into which $58m has already been sunk for the building of an interdenominational national cathedral.

“I made a pledge to almighty God that He was gracious enough to grant my party, the NPP, and I victory in the 2016 elections after two unsuccessful attempts, so I will help build a cathedral to his glory and honour,” President Nana Akufo-Addo said at the sod-cutting ceremony in 2020.

“The interdenominational national cathedral will help unify the Christian community and thereby help promote national unity and social cohesion,” he said.

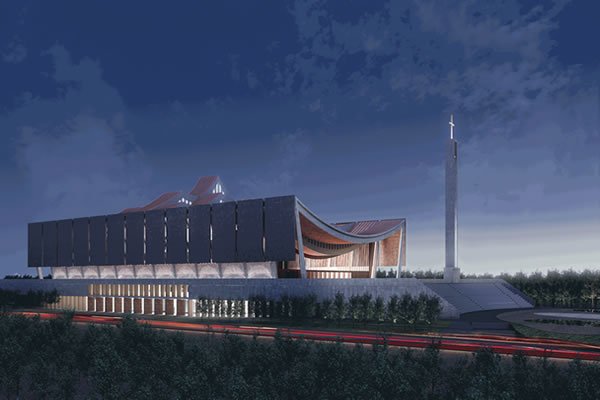

But construction of the president’s pet project, due to cover 3.5 hectares (9 acres) of prime Accra real estate, has stalled since June due to lack of funds. If it weren’t for the cranes and artistic impressions of the project surrounding the construction zone, it could pass for an abandoned illegal mining site.

Like Akufo-Addo, two-thirds of Ghana’s estimated 30 million people are Christians even though it is an officially secular nation.

There are an estimated 10,000 churches nationwide, and open-air preaching is commonplace on public transport, at bus terminals and at road intersections. According to the Africa Oxford Initiative, Accra alone has about 10 churches per square kilometre.

The president saw the cathedral as a way to unite these believers, but instead, it has split them into two major groups: those who want to see the church built to upgrade Ghana’s state infrastructure and those who see it as a waste of state resources, given the country’s economic state.

‘Financial burden on the state’?

Ghana, a major cocoa producer and leading exporter of gold, is facing its worst economic crisis in decades and has racked up a debt of $45bn by the end of November.

The cost of living is high in the West African state with inflation hitting a record 54 percent in December, the highest in 21 years. Rents, fuel and transport prices have risen, and about a quarter of the population live below the poverty line, according to the United Nations Development Programme and the Ghana Statistical Service.

Funding for the national cathedral has been shrouded in secrecy, but last year, the secretariat in charge of the project said the cost, initially estimated at $100m, has now quadrupled due to inflation.

While presenting the 2019 budget to parliament, Finance Minister Ken Ofori-Atta promised the cathedral would not “put undue financial burdens on the state”.

He said most of the costs would be covered by donations and the government was providing only the land and an unspecified amount of “seed money for the preparatory phase”.

However, that has not been the case. Most of the $58m spent so far has come from the national coffers, Ofori-Atta himself told parliament when it summoned him in November for a censure hearing.

A month later, parliament blocked a budget allocation of $6.3m that the government had wanted to continue the project even as Ghana struggles to restructure its debt to qualify for a $3bn loan from the International Monetary Fund.https://www.youtube.com/embed/br6fLenpRfk

Strategic project or misplaced priority?

The government argues the cathedral will bring enormous long-term economic benefits while transforming Ghana into a religious hub, creating jobs and accruing more revenue for the state.

The plan is for the cathedral’s 5,000-seat, two-level auditorium, which could be expanded to have an additional capacity of 15,000, to serve as a sacred space and facility for national events like state funerals and presidential inaugural services. It would also be home to Africa’s first Bible Museum and Documentation Centre. In addition, the cathedral would have a music school, an art gallery, shops and a national crypt for state burials.

Paul Opoku-Mensah, executive director of the national cathedral secretariat, said the location of the cathedral is strategic.

“Most of the great cathedrals are situated near the epicentres of power, particularly parliament because that’s where the formal religious rites take place, like the swearing-in ceremonies of presidents,” Opoku-Mensah told Al Jazeera. “Such upfront massive investments bring in revenue to create employment, and … we’ve integrated the elements that will drive traffic [and revenue] to Ghana.”

Akufo-Addo is serving the second of his two constitutionally allowed four-year terms, which expire in 2024. Some of his critics have called for the project to be scaled down over fears that it could be abandoned after his exit from office.

But the president is not backing down.

In January, he made a personal donation of $8,000 towards the construction costs, saying nothing will stop him from fulfilling his pledge to God.

“I am determined, come what may,” Akufo-Addo said. “I have two more years that, whatever the case, the national cathedral will be at a very advanced stage before I leave office. I think it is important that we do it.”

Beyond the president, the project has a number of high-profile defenders. One of them is popular actor Majid Michel, also an evangelist.

“Certain decisions can be taken today, and the people around can never understand why those decisions have been made until maybe 10 years after,” he told Al Jazeera. “When Kwame Nkrumah [Ghana’s first president] was constructing roads then, people were fighting him. They even staged a coup against him. But now we use the motorway more than anybody else, and it comes with economic benefits.”

“It’s all about perspective,” Michel said. “… Most of the developed countries had museums years back, but today, they are fetching them a lot of money.”

“I doubt a time will come that we’ll say the cost of living is now better for us to do what we want to do,” Kwadwo Opoku Onyinah, chairman of the cathedral project’s board of trustees, told Al Jazeera. “The cathedral will be a tourist attraction. … It won’t be a white elephant. Even at the foundation stage, people are still coming from outside to visit the site.”

‘The most reckless decision … in the history of this country’

But critics and the opposition accuse the government of using the project to milk state coffers in the name of religion, and some see the state-backed construction as a misplaced priority.

“We should be building hospitals and schools,” actor and activist Yvonne Nelson told Al Jazeera. “People are dying. I don’t think any Ghanaian is complaining about where to worship, but we complain about the health sector. We complain about schools. For churches, we have many. God looks at the heart, and so let’s get our priorities right.”

Ransford Gyampo, professor political science lecturer at the University of Ghana, agrees.

“It’s quite strange that we are putting religion ahead of development,” he told Al Jazeera. “We have pressing issues, such as lack of funding for the national school feeding programme involving schoolchildren, and our priority as a country is to build a cathedral for God. God will not be happy with us. Who said God lives in cathedrals?”

“Our public hospitals are without dialysis machines for kidney patients,” Gyampo said. “… Can’t we channel the same energy we are putting into raising funds for the cathedral into attracting investors to this country? Look at how bad our economy is now.”

Contrary to Ghana’s procurement laws for projects using taxpayers’ money, no bidding process was conducted for the cathedral’s design contract. It was awarded to respected Ghanaian-British architect David Adjaye for a reported $22m.

Samuel Okudzeto Ablakwa, an opposition member of parliament and a critic of the project, has accused the board of diverting $206,658 to a private company of one of its members. The Reverend Kusi Boateng is accused of using a different name to establish the firm, JNS Talent Centre Ltd, to receive the funds.

The cathedral secretariat denied the allegation, saying the amount was repayment for a loan taken from Boateng’s company to pay contractors.

“This was not an illegal payment but rather a refund of a short-term, interest-free loan made by JNS to top up the payments to the contractors of the national cathedral,” the secretariat said in a statement dated January 16. “This support was sought from a national trustee member, Reverend Kusi Boateng, due to a delay in the receipt of funds to pay the contractors on time.”

The series of controversies has caused two members of the board of trustees – popular Christian leaders Mensa Otabil and Dag Heward-Mills – to resign. Heward-Mills expressed his frustration about how the project and the board were being run in his August resignation letter addressed to Akufo-Addo and the board.

“You may recall I have spoken passionately and written extensively about the costs, the design, the location, the fundraising, the mobilisation of the churches, and the role of the trustees,” said the televangelist, whose Lighthouse Chapel International church reportedly has a network of 1,200 branches in 61 countries. “These, if heeded, would have made our project more achievable. Generally speaking, my inputs, my opinions, and my letters have been trivialised and set aside.”

In January, two others members of the board – Archbishop Nicholas Duncan-Williams and the Reverend Eastwood Anaba – wrote to the cathedral secretariat to call for an immediate suspension of construction pending an audit of the project.

“The current economic climate in Ghana presents obstacles to the timely construction and completion of the national cathedral,” they said in a joint memo. “We, therefore, resolve: that in the spirit and cause of transparency and accountability to the Ghanaian people, the current board of trustees of the national cathedral shall appoint an independent, nationally recognised accounting firm to audit all public funds contributed to and spent by the national cathedral.”

In response, the board chairman said Deloitte would conduct the audit.

The firm has been asked to determine whether the state is fully funding the construction or if there is any misappropriation of funds. Deloitte has yet to submit its audit report.

Another criticism of the project is the demolition that the government carried out to make way for the cathedral. Bungalows occupied by senior judges were removed along with a training school belonging to the judiciary, the country’s main passport issuing office, a scholarship secretariat, a diplomat’s residence, a luxury apartment and a host of private businesses.

One of the affected private firms is in court demanding compensation.

“To us, it is the most reckless decision any president has taken ever in the history of this country,” Ablakwa told Al Jazeera. “Look at the compensations we need to pay and the rebuilding of some of these structures. So when you add these together, our conservative estimate is that we will be spending in excess of $1bn because that $400m, which is being bandied around, is just an empty shell, and it does not address all the exclusions.”

‘A symbol of corruption’

Not all Christian leaders have supported the president’s plans.

“There is time for everything,” Fred Korankye-Mensah, presiding bishop of the Accra-based Transformation Assembly Church, told Al Jazeera, arguing that building the project at a time of economic turmoil is insensitive to Ghanaians. “There is nothing wrong with building a national cathedral, but the timing is not right. We can put the money into other things, such as fixing our roads and healthcare issues.”

Some point next door to neighbouring Ivory Coast for a cautionary tale. It is home to the only basilica in Africa and the largest church in the world. Built by former President Félix Houphouët-Boigny, the Basilica of Our Lady of Peace cost $200m to $300m and has the capacity to seat 18,000 worshippers.

These days, an estimated $1.3m is used for its annual maintenance even though an average of fewer than 1,000 people attend regular services.

“Today, the Ivorian cathedral has become a white elephant,” Ablakwa said. “Their former president also dreamt just like our president to build a basilica, so if the Ivorian cathedral didn’t live up to expectation, why will a Ghanaian cathedral be different?”