What’s happening

When the coronavirus first began spreading from China to the rest of the world, public health experts issued dire warnings about the toll the virus would take on poor countries.

The United Nations predicted in early April that as many as 3.3 million people in Africa may die from COVID-19. Philanthropist Melinda Gates warned of “bodies out on the street” on the continent.

Similarly, dire forecasts were made about developing nations in Latin America, Asia and elsewhere.

In March and April, however, the worst impacts of the pandemic were concentrated in wealthy countries in North America and Europe, while the bulk of the developing world reported remarkably low numbers of infections.

At the end of April, low-income countries accounted for just 14 percent of global COVID-19 deaths despite being home to 84 percent of the world’s population.

That trend has shifted significantly over the past two months. Rich countries, with the obvious exception of the United States, have gradually gotten their outbreaks under control.

At the same time, the situation has gotten much worse in developing countries. Latin America is now the global epicentre of the pandemic, driven by major outbreaks in Brazil, Chile, Peru and Mexico. The number of new daily cases in India has skyrocketed as lockdown measures there are being lifted.

Why there’s debate

Some experts are concerned that developing nations are seeing the beginnings of the worst-case scenarios that were predicted in the early stages of the pandemic.

Many of these countries are home to incredibly densely populated cities with limited access to sanitation and poor public health infrastructure — conditions that could lead to a devastating outbreak. It’s also possible that limited testing has underrepresented the true size of the outbreak until recently.

While reduced travel from Western countries may have delayed the spread of the virus, it appears now to have taken hold in several vulnerable countries, epidemiologists say.

Poorer nations also are particularly at risk of severe economic consequences of the pandemic, which may compel their governments to relax lockdown measures in order to avoid food crises within their borders.

While the situation in some places appears dire, there are reasons for optimism, some experts argue.

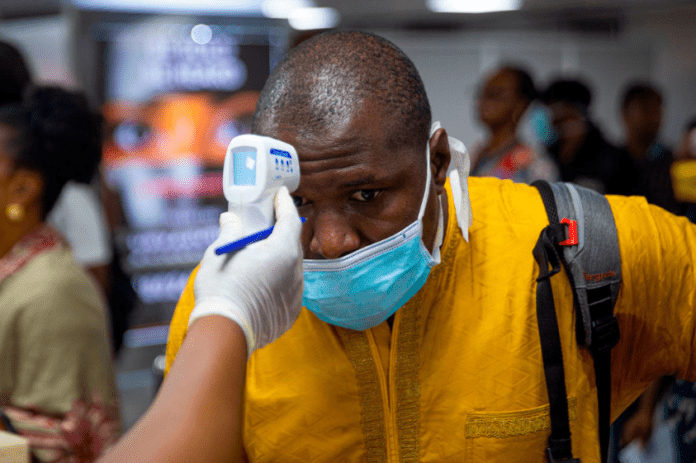

For all the challenges they face, many developing nations have done an excellent job containing the spread of the virus. Years spent combating diseases like HIV, malaria and Ebola mean that the epidemic response in some countries is much more sophisticated than people in the West might expect.

Conditions on the ground may also help limit the severity of the outbreak in some places.

Insufficient roads and lack of public transport can make it difficult for the virus to travel from one community to another. Developing nations also tend to have much younger populations than wealthy countries — the median age in Africa is 20 years old — which could mean fewer deaths even if there is a high number of cases.

Perspectives

What’s next

The next several weeks will be critical in deciding how bad the pandemic gets in the developing world. Countries that are already being hit hard, like Brazil and India, could see their outbreaks grow to rival the U.S. for worst in the world if trends continue. Nations that have so far contained the virus, like Vietnam and Uruguay, may not experience significant outbreaks at all.

Unless something changes, a handful of developing nations will be devastated by the virus

“If the curves in these countries do not start flattening, the damage will be worse than anything we’ve seen in the West. The population density and sanitary conditions make the rapid spread of the disease seem inevitable.” — Fareed Zakaria, CNN

Many poor countries have taken smart steps to effectively contain the virus

“Western media sources tend to emphasize developing countries’ challenges rather than their achievements. … But the available evidence suggests that developing countries have tackled COVID-19 not through luck or chance, but rather through the diligent efforts of their politicians and their populations.” — Michael Hobbes, HuffPost

The pandemic is just one of several crises facing the developing world

“Some nations, particularly in the developing world, find themselves under extraordinary strain as they simultaneously contend with other outbreaks, chronic public health problems and challenges posed by government mismanagement, poverty and armed conflict.” — Kirk Semple, New York Times

The delayed arrival of the virus gave developing nations time to get ready

“Many countries that had additional time to prepare have used it well. Contact tracing ramped up more quickly in some African cities than American ones.” — Dave Lawler, Axios

Elderly people aren’t the only ones at high risk in poor countries

“The reasons more middle-aged people are dying in poorer countries include demographics, a greater prevalence of underlying diseases like diabetes, and weaker health-care systems. The upshot: People in their 50s and 60s who get infected are more likely to die in places like Mexico and India than in the U.S. or Europe.” — David Luhnow and José de Córdoba, Wall Street Journal

Decades of progress may be set back because of the virus

“We are … concerned about long-run effects arising from the shutting down of economies: the loss of education among girls, the suspension of vaccinations among children, the falling back into poverty of those living close to subsistence.” — Pinelopi K. Goldberg and Tristan Reed, Brookings

Poor countries can’t withstand a major economic hit

“Isolation measures threaten the food security of millions of people. This means that even if the epidemic is successfully managed at the health level, the impact on economies — and people — will be devastating.” — Borja Santos Porras, Conversation

Dense cities in developing nations face severe risk

“The coronavirus preys on the weaknesses in many poorer countries. It spreads rapidly in densely packed neighborhoods where hygiene is a challenge. People working as day laborers and in the informal sector can’t stay home if they want to feed their families.” — Luciana Magalhaes and Juan Forero, Wall Street Journal