A Governor on the ropes

Rattled by unprecedented demonstrations against his tenure by Ghana’s political opposition, the governor of the Bank of Ghana described the protestors as “hooligans”.

The choice of language is uncharacteristic of Ghana’s suave and urbane leading central banker. When he was first appointed, few would have guessed that his term would see such a spectacle. Rarely, anywhere in the world, are central banks the usual target for mass protestors. And this Governor in particular came to office enjoying massive elite confidence.

For nearly a decade, until he decamped to the African Development Bank (AfDB) in 2011, he helmed the research function for the Bank of Ghana. In this role, he highly supported Ghana’s small but committed think tank and research-oriented activist community. When our community mobilised against what we saw as lazy banking, the Governor, in his then research-led capacity at the central bank, was a source of analytical influence.

Changing Habits

Then he got into the apex role and everything changed. He began to push poorly conceived policies such as forcing massive recapitalisation requirements across the banking industry when the real challenges were poor capital adequacy owing to years of failure to deal with toxic assets and poor corporate governance. Protests, warnings, and laments went unheeded. He stopped listening to the independent policy community, treating their views with contempt. Many specialised banks catering to niche segments of the economy were forced to close down for no sensible reason. Despite the brutal weeding out of small and specialised banks, capital adequacy continues to be a problem for a quarter of Ghana’s banks. And the fruits of the failed recapitalisation program are still shedding their seeds.

Legacy Unravelling

Meanwhile, the one bold action that could have defined his legacy, the closure of insolvent banks that previous governments did not have the stomach for, has had its aftermath badly mismanaged.

Whilst, elsewhere, publicly funded bank bailouts and takeovers have yielded nice profits for the State, a thoroughly lacklustre recovery and liquidation process in Ghana has saddled the taxpayer with billions of dollars of liabilities with no prospect of getting most of the money back. The US government, for instance, has earned more than $30 billion on its bailout investments due to effective recovery management.

After mooting costs in excess of $3.5 billion three years ago, following massive failures in the recovery & liquidation program (with a lower than 10% rate recorded in one category, for example), the Bank of Ghana stopped accounting to the public altogether.

One should therefore not make the mistake of assuming that the $5.45 billion loss that has triggered these unprecedented protests for the removal of the governor came in a vacuum. The disaffection has been brewing for a while. Judging from the history of missteps outlined above, one should also be inclined to take the central bank’s loud protests of innocence with a massive sack of salt.

Here is the case for the prosecution.

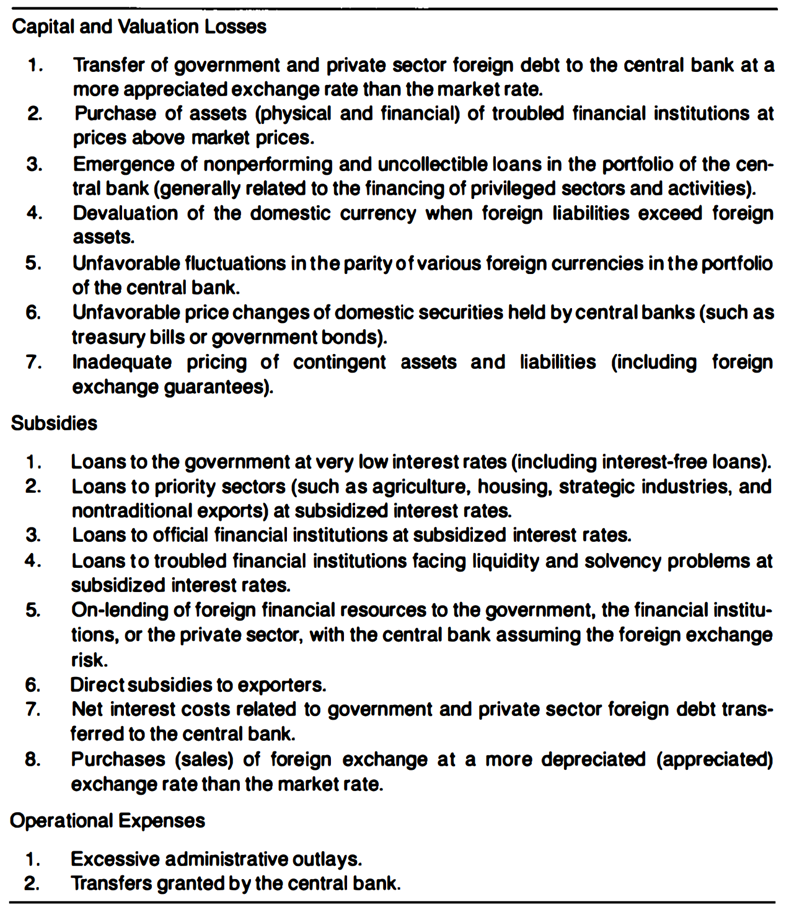

First, let’s get this out of the way: a central bank can indeed make losses, and many routinely do. As far back as 1993, the IMF’s Alfredo Leone did a fine paper cataloguing the possible sources and ramifications of central banking losses.

What has caused a ruckus in Ghana is thus not the mere fact of lossmaking, but rather the scale of it, the causes, and the surrounding sleaze.

Sheer scale of the Loss

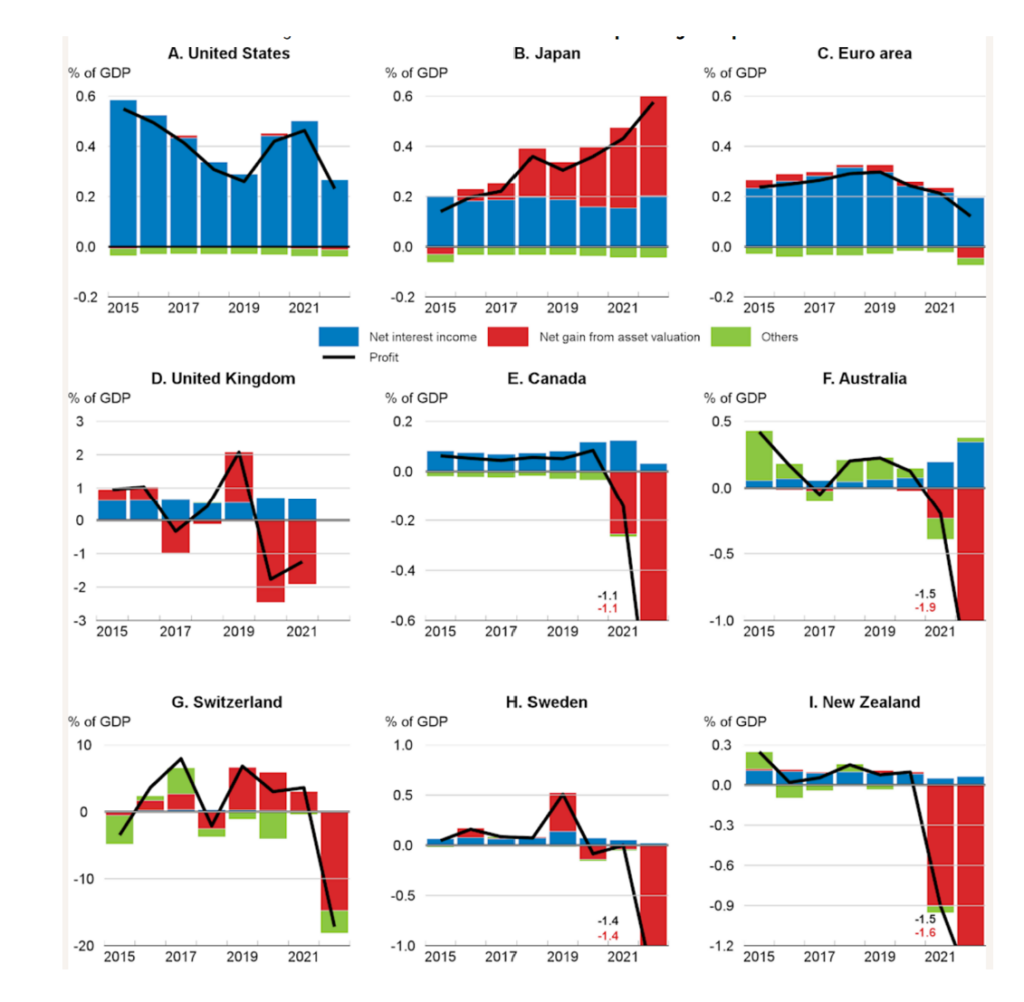

The Bank of Ghana’s declared losses for 2022 are on the order of 8% of Ghana’s entire GDP. As the array of charts below from the OECD (Ono & Pina, 2023) shows, the size of the loss in Ghana’s case is truly phenomenal.

Bank of Ghana lied blatantly about peer comparisons

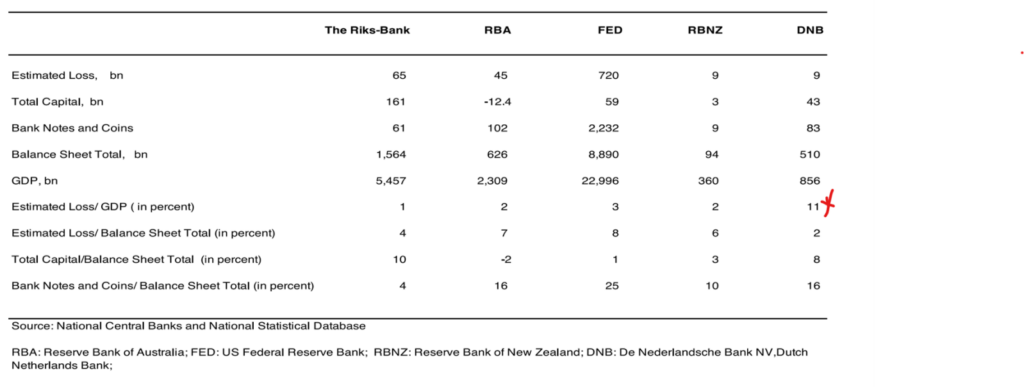

What is worse, the Ghanaian central bank, to further absolve itself of all blame, proceeded to publish a table attempting to underplay how bad its losses were in comparison with peers elsewhere. It comically inflated the losses of the Dutch central bank from 1% of GDP to 11% in order to mask its own unprecedented challenges.

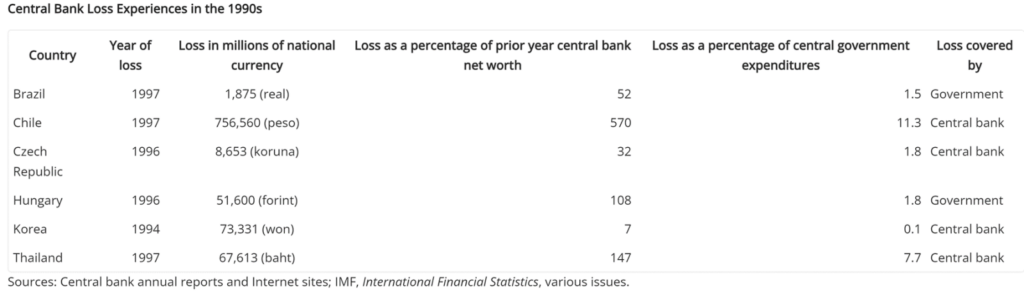

But comparing it to GDP does not do full justice to the stupendous scope of the mess. When compared to the total equity of the Bank of Ghana (BoG) in the previous year, the resulting ratio is nearly 1200%. This is eye-popping from a historical point of view. For instance, a chronicle of historically significant central bank loss incidents by economists John Dalton and Claudia Dziobek (2005) from the 1990s produces a comparative average of just 35% (compared with BoG’s 1200%, that is).

The causes according to the Bank of Ghana

The BoG has listed four main causes for the loss:

- A 50% haircut on its holding of government debt

- Exchange rate losses

- Increases in operational expenses

- Interest expense on monetary policy operations

Of these four reasons, only the last can be adduced to support the BoG’s innocence, but it accounts for only 6% of the losses. The three other causes stem from underlying problems for which the BoG cannot in any way escape blame.

Impact of the Debt Restructuring Program

A truly independent central bank would not have been left holding the can in the way that the BoG was exposed during Ghana’s disorganised domestic debt restructuring process (DDEP/DDR).

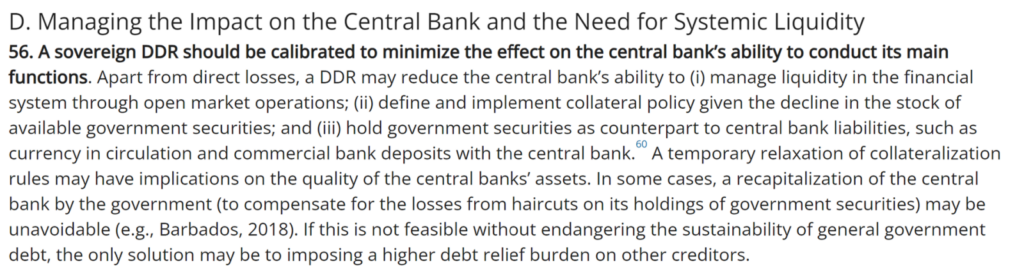

As the IMF itself has warned, central banks should shield their credibility when participating in domestic debt restructurings.

Every serious central bank is thus careful not to allow itself to be used for political convenience by the fiscal authorities (the central government) when they spend their way into a ditch.

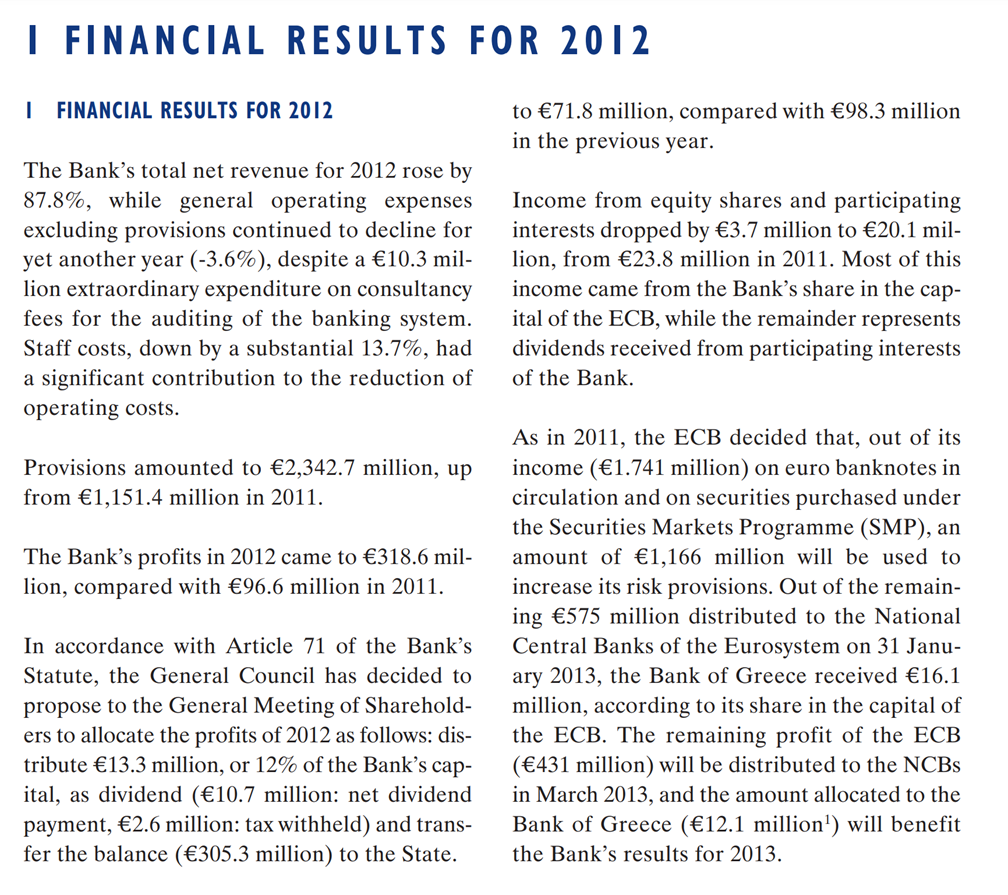

In Greece, during that country’s 2012 debt restructuring episode, the central bank cleverly demanded that important state assets be pledged onto their books in order both to maintain balance sheet integrity and to keep the politicians honest.

In Barbados, a central bank recapitalisation plan was built right into the domestic debt restructuring program.

That is why during the heady days of the Greek debt crisis in 2012, the country’s central bank actually turned a profit (see detailed extract from the relevant annual report).

In short, the BoG, by being too cosy with the politicians, by lacking a serious negotiating spine, by failing to show tough love to the fiscal administrators, and by sheer cluelessness of the political economy of Ghana, has seriously damaged its reputation by destroying its balance sheet.

Why the massive debt holdings in the first place?

And how come the BoG was holding so much government paper in the first place? It claims that this was because prudent investors didn’t want to buy government debt beyond a certain limit, yet the government was determined to live above its means, so the BoG had to step in, like a daft dealer with a soft spot for a junkie.

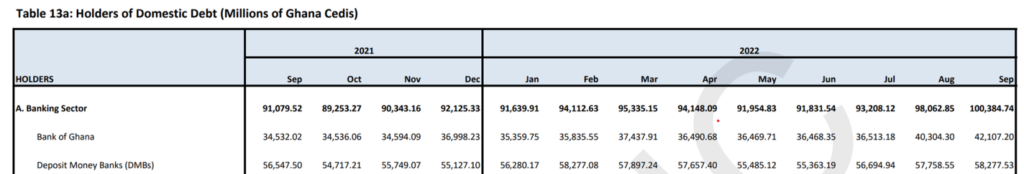

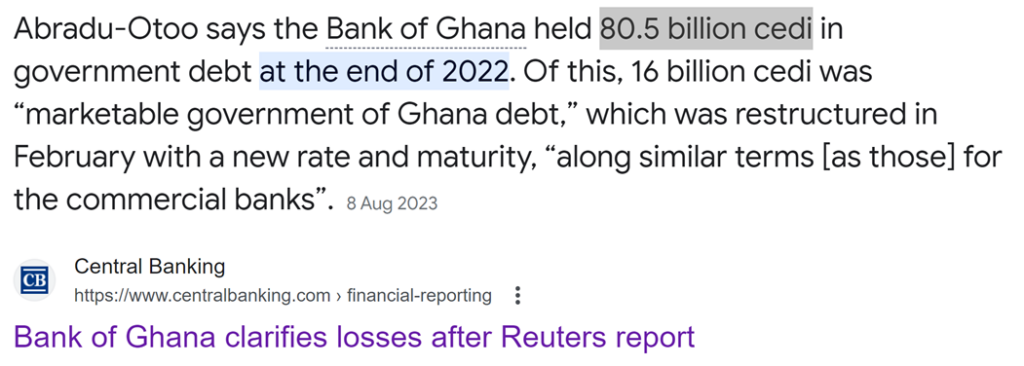

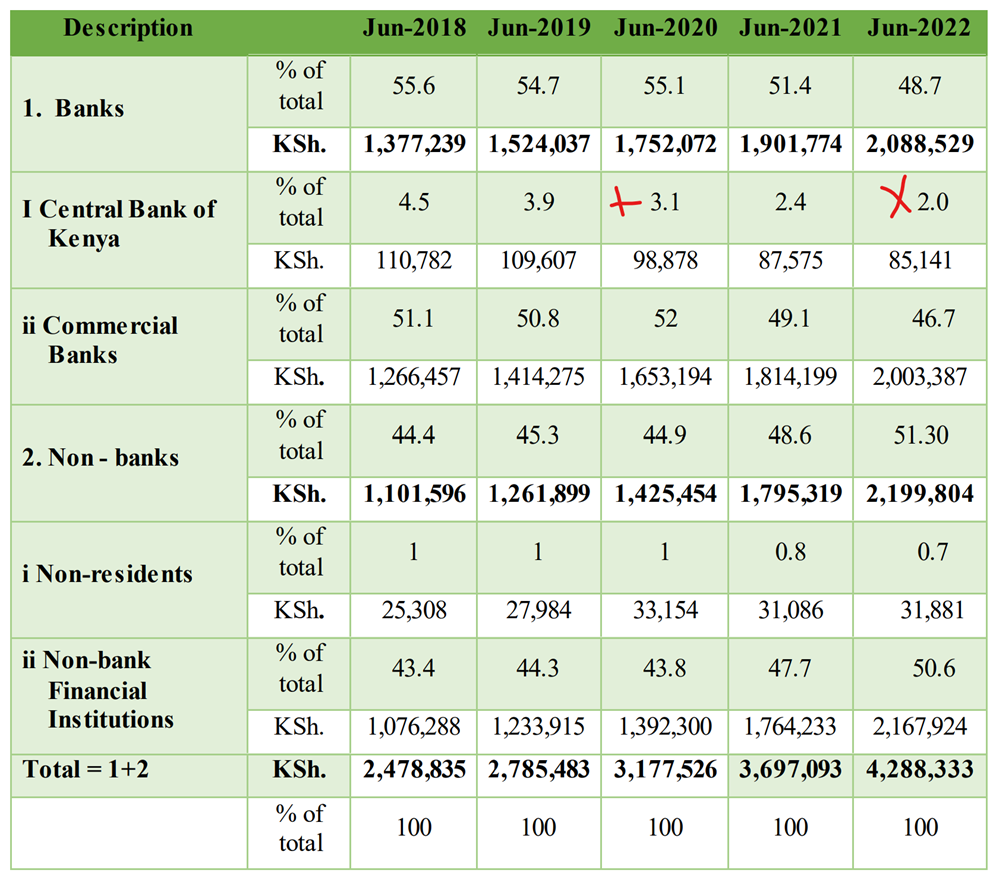

Hence, in 2022, the year in which the loss was recorded, BoG alone was responsible for more than 40% of all banking sector lending to the government. Or, at least, for the outstanding stock of the sector’s debt to government.

But this is not telling the full story. Between September and December ending of the same year, the BoG doubled its holdings, according to interviews given by its Head of Research. Let that sink in: in the course of just three months, BoG printed or conjured nearly 40 billion Ghana Cedis (GHS) or ~$4 billion to protect the government from the need to kick its habit of overspending.

Compare this situation with that of one of Ghana’s closest peers, Kenya, where the central bank held just 2% of government debt (versus 46%+ held by the private banking sector).

The loose quasi-fiscal behaviour is part of a pattern

Perhaps, Ghanaians would have been less infuriated had the BoG’s crimes been limited to these technical and wonkish infractions. But imagine their alarm when it then also emerged that the central bank has been engaged in dodgy procurement and reckless overspending on itself; and was, in addition, dishing out lavish packages to its Board of Directors.

The $250 million Headquarters project

A cynic once said that, “how you do anything is how you do everything”. Those inclined to cut BoG some slack for the losses stemming from its reckless lending to the central government have to face the shambolic project management that has seen costs of its new headquarters balloon by nearly 300% at design stage.

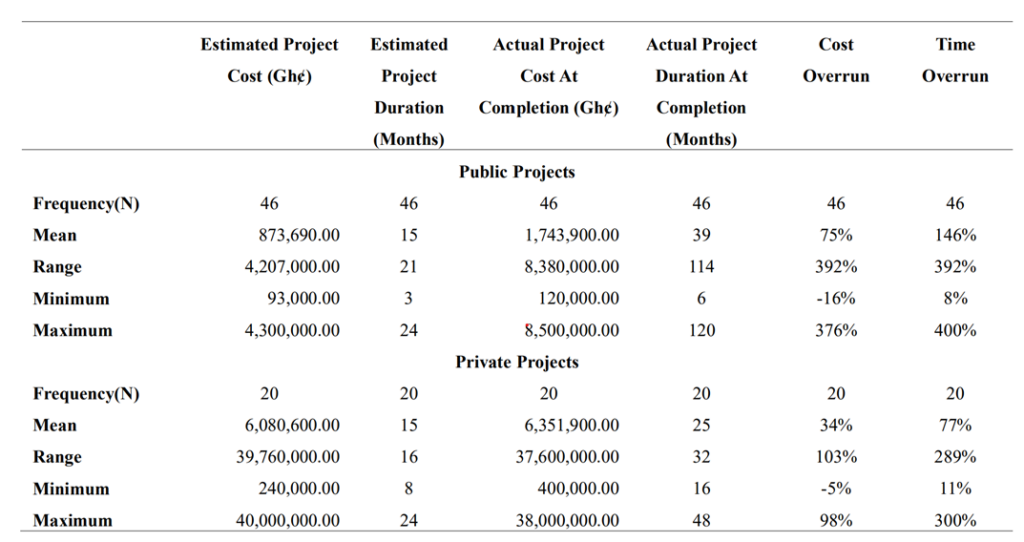

Documents from the procurement regulatory authorities show that even before construction could take off, approved estimates shot up from ~$80 million to more than ~$200 million. Now that the construction rate is at roughly 40%, total cost projection is between $250 million and $300 million. In fact, cost and time overrun models suggest that cost variations worsen during actual construction, so the total cost may well hit $500 million.

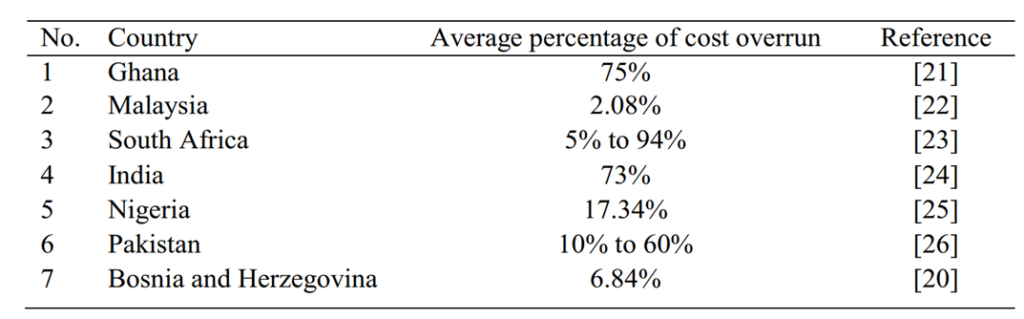

These cost overruns are far above the medians recorded in Ghana and the region by experts, as shown below.

Source: Albtush et al (2021)

The 300% to 500% cost overrun numbers emanating from the BoG’s headquarters project (compared to median rates of 75% in Ghana) illustrate a general pattern of disregard for prudent financial management.

This is on top of the fact that the BoG has revised designs to remove the high-value features such as the state-of-the-art data center, currency processing system, and integrated security management system.

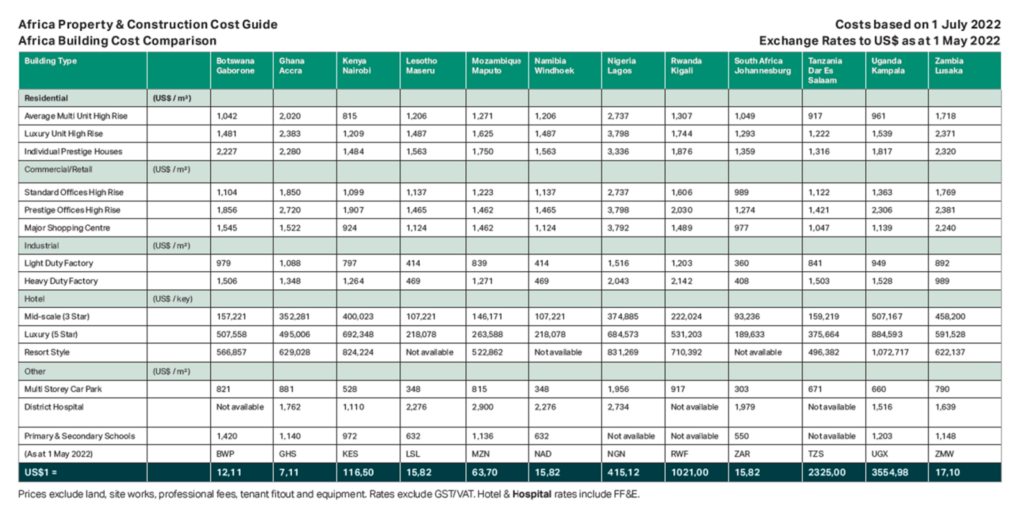

In its defence, the BoG has provided benchmarking data from the Africa Property & Construction Cost Guide.

But its computations are highly misleading because it has used the average costing for “prestige office high rise” for the entire project scope when, in actual fact, 60% of the gross project area is covered by other elements such as a multi-storey car park.

Properly weighting the different components of the project yields a per meter square cost for the project that deviates from the benchmarking guidance by nearly 70%.

On top of all this, the BoG chose to use restrictive tendering on national security grounds when none of the qualified vendors has any special national security clearances that set it apart from any of the 100 or so contractors in Ghana that would have qualified to place bids in a truly transparent and merit-driven process.

A Pattern of Procurement Abuse

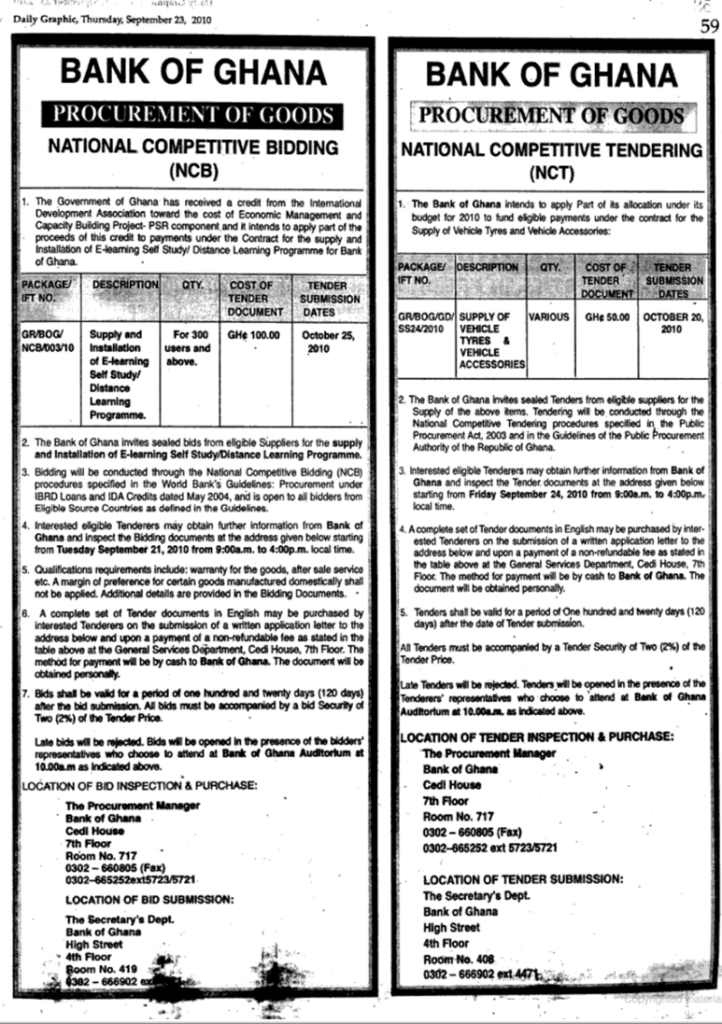

The BoG’s spending inefficiencies are revealed through a record of poor and sleazy procurement decisions.

The BoG has invested, and continues to invest, in a raft of ventures, ranging from hospitality facilities to medical installations. In many of these cases, the procurement practice is far from transparent, and rarely is it ever above board.

For example, a number of contracts for multimillion dollar hotel facilities have been awarded without competitive tender.

In one particularly egregious instance, a contract already awarded to a company called, Maripoma, was stripped off and awarded without competitive tender to a favourite, DeSimone, which has also benefitted from non-competitive invitations to bid and actual contracts in the Bog headquarters and national cathedral episodes, respectively.

The national security arguments ring completely hollow not just because the corporate favourites that win these awards have no special national security clearances over and above those that are denied the opportunity, but also because we see a shift in favourite contractors whenever new governors come to office. Furthermore, contractors excluded from bidding on national security grounds by one public agency often undertake work of similar scope awarded by other agencies, sometimes even under the same dubious national security pretences.

Lastly, and perhaps worse of all, the Bank of Ghana routinely buy ordinary items, like Toyota vehicles, to the tune of millions of dollars using the same restrictive tendering and single-sourcing approaches.

Per this author’s calculations, more than 90% of routine procurement in the last few years at the BoG bypassed competitive tendering or otherwise fell short of standards.

What is sad is that it wasn’t always like this. Under some previous administrations, the BoG regularly resorted to competitive tender for most of its procurement needs.

Board largesse

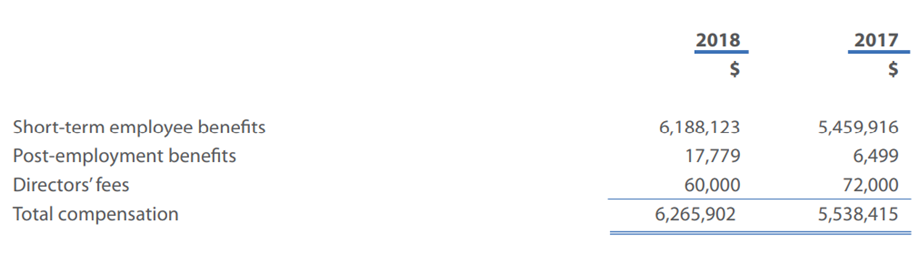

Perhaps, one reason why the management of the Bank of Ghana hasn’t been reined in despite all the profusive abuse of procurement standards, lavish overspending, and reckless quasi-fiscal behavior, is the shrewd distribution of lavish treats to the BoG’s board members.

For example, consider that the entire annual cost to Barbados for maintaining its central bank board is $60,000.

In Ghana, the equivalent spending is close to $800,000. The cost of upkeep of the BoG’s board is more than 300% higher than that of the Central Bank of Kenya’s.

“Board capture” through treats and perks is a well-known tool used by some corporate management for suppressing true oversight and fiduciary controls.

The sum of it all

It should be evident from all the above that the reasons given by the Bank of Ghana to absolve itself of all blame in the current controversy are hollow. The stiff-necked refusal to accept the need for serious policy and corporate governance reforms at this very sensitive institution, whilst reminiscent of the general posture of the current political administration, does not become such a critical institution.

If the governor does not change the approach to engaging with critics and the public, show signs of genuine listening, and commit to a transformative program to rebuild trust, his term is likely to go down in history as the worst Ghana has ever seen. Which would be a real shame, given the hopes he inspired when he was first appointed.