Though often celebrated for its strides in increasing access to education, Ghana’s educational system remains rooted in outdated paradigms that hinder its ability to equip students for the future.

Despite decades of independence and national growth, Ghana’s approach to education is still heavily influenced by colonial legacies and entrenched traditions of instruction that prioritise knowledge acquisition and sheer recall over practical thinking and practical skills, as well as the application of knowledge and skills in meaning-making.

In most cases, the outlook of teaching and learning focuses on the present instead of emerging issues.

Given this, a serious disconnect occurs between what students are taught and the demands of emerging job markets, which are greatly determined by the rapidly evolving technologies and their emerging trends.

To curb the increasing problems of youth unemployment and unemployability, there is a need for a critical look and a paradigm shift from the existing systems of teaching and learning and by extension, methods of assessment, to a more pragmatic system that looks into the future.

Enduring Legacy in Colonial Foundations

The foundations of the formal education system in Ghana can be traced back to the colonial era, particularly the era of British domination. Education was designed primarily to produce a small educated elite who could support the colonial administration.

Although the focus seemed to be on rote memorisation, rigid curricula, and the propagation of British values, with little regard for local context or the practical needs of the broader population, the primary aim was to train a section of Ghanaians to fill the needs of the job market per the description of the British coloniser as well as helping to maintain colonial control over the local populace.

After Ghana’s independence in 1957, several attempts have been made at reforms in the education system to reflect the needs of the nation.

Mention can be made of the Free Universal Primary Education (FUPE), The Junior Secondary School system that is aimed at introducing practical subjects and activities that allow students to acquire occupational skills, which after an apprenticeship might lead to the qualification for self-employment, the Free Compulsory Universal, Basic Education (FCUBE) programs well as more recently, the Standard Base Curriculum (SBC).

There is also been some credible attempts at integrating the study and use of ICT into the educational system at all levels.

However, despite all these reforms, the system largely retained the structural and philosophical underpinnings of the colonial era. This lingering legacy continues to influence the content, teaching and assessment of the reviewed curriculum.

It still hinges on knowledge acquisition and writing of non-differentiated standardised examinations, rather than fostering practical skills, critical thinking, and innovation necessary to succeed in the modern world.

The Emphasis on Mere Knowledge Acquisition

Perhaps a distinct flaw in Ghana’s educational system is its disproportionate emphasis on overly knowledge acquisition, which rewards the ability to recollect information as they are with very little attempt at practical thinking or application.

This academic-centric approach has its roots in a deeply ingrained belief that success is measured by academic qualifications determined through a standardised examination that does not give room for a differentiated set of questions.

Although examinations and certificates may be important indicators of knowledge, they are not enough to prepare students for the increasingly complex and dynamic demands of the job market, which is hinged on emerging trends and deep reasoning that can generate well-meaning results.

Learners are often required to memorise vast amounts of information without necessarily understanding its practical applications. This becomes a form of passive learning that stifles creativity, critical thinking, problem identification and the generation of workable solutions.

It further militates the learner’s ability to generate essential skills such as digital literacy, technical proficiency, and entrepreneurial skills, which are vital for making meaning in an interconnected technology-driven world.

This rigid nature of the educational system contributes to a decline in the fostering of the entrepreneurial mindset necessary to drive economic growth.

It could also be realised that the structure of courses and subjects taken at almost every level of the education system is usually not in configuration with the realities of entrepreneurship, innovation, and practical skills in real-world situations.

Given this, many young people become unemployable and unprepared to harness opportunities in the growing sectors of the job market.

Infrastructural and Resource Challenges

Another serious shortcoming in Ghana’s education system is the significant infrastructural and resource-related challenges.

It should be reiterated that over the years, some progress has been made in expanding access to education, particularly through the implementation of policies like free basic education and the construction and equipping of school buildings across the country, there remains a glaring discrepancy in the quality of education across the country.

Urban schools, although better resourced, are often overcrowded, while rural schools continue to grapple with inadequate facilities and a shortage of qualified teachers.

These infrastructural deficiencies further worsen the quality gap between students in different regions.

In rural areas, where resources are even scarcer, learners often attend schools with poor facilities, insufficient teaching and learning materials, and inadequate teacher training. As a result, many children do not achieve the educational outcomes and it perceived employable skills required for the job market or even self-employment.

Investing in teacher training is crucial to bridging the gap between urban and rural education. This involves providing regular professional development programs, such as workshops, seminars, and courses, to enhance teachers’ subject matter expertise and pedagogical skills.

Additionally, mentorship initiatives need to be improved to pair experienced teachers with newer educators, offering guidance and support to help them navigate the challenges of the profession.

Furthermore, technology integration training is essential in today’s digital age. Teachers should be equipped with the skills to effectively incorporate technology into their teaching practices, making learning more engaging and relevant to students’ lives.

Context-specific training is also vital, as it allows teachers to address the unique needs of their students and communities.

Moreover, continuous assessment and feedback are critical components of effective teacher training. Regular evaluation of teacher performance, accompanied by constructive feedback, supports ongoing improvement and helps teachers refine their craft.

These comprehensive investments in teacher training programs will help improve the quality of education, enhance learners’ outcomes, and better prepare them for the demands of the modern world.

The Paradigm Shift and the Way Forward

Considering the mitigating issues discussed earlier, it is undeniable that there should be a serious paradigm shift in our educational system. Recent initiatives, such as the “Free Senior High School” policy, have made significant strides in increasing access to education.

There is also a gradual review of the curriculum to suit international standards. However, the system is still grappling with the issue of just acquiring certificates through standardised education rather than acquiring knowledge and skills through practical thinking.

To stay competitive globally, Ghana must prioritise education reform, focusing on practical skills development, critical thinking, and problem-solving. Public-private partnerships can play a vital role in providing resources and expertise to support education reform.

By working together, we can create an education system that truly prepares students for the demands of the modern world.

Conclusion

Ghana’s educational system, despite its progress in increasing access to schooling, remains largely attached to the educational principles of the past.

To secure a future where Ghanaian youth can compete on the global stage and contribute meaningfully to the nation’s development, the education system must evolve.

This evolution requires a fundamental shift from just the acquisition of knowledge and reproducing them through standardised examination to one of practical thinking, where students can readily identify and apply such knowledge in solving simple to complex problems of real-world challenges.

It is time Ghana’s educational system moves beyond vain knowledge and certificate acquisition to a system that aims at truly preparing its children for the future through a comprehensive, forward-thinking approach that hinges on using innovation and creativity to solve complex global problems.

Anything short of that will be preparing its growing population for the past that no longer exists.

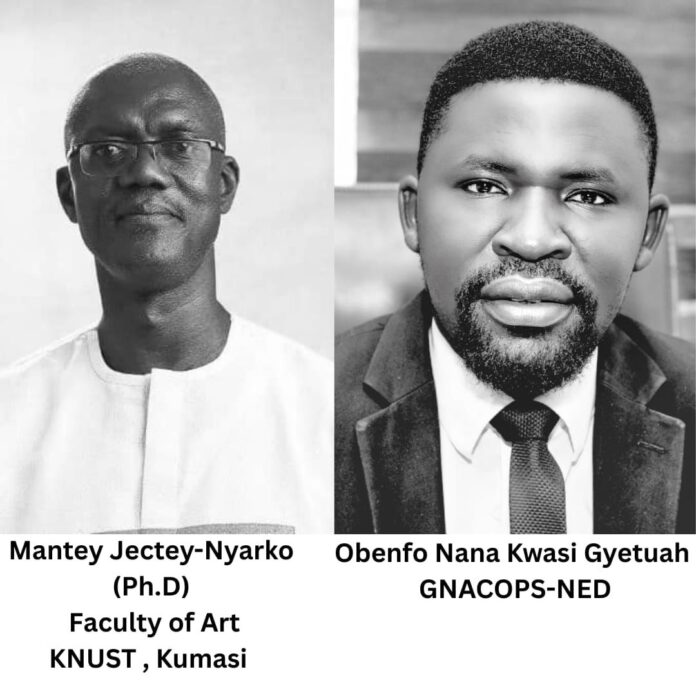

Authors:

Mantey Jectey-Nyarko (Ph.D)

Faculty of Art

KNUST-Kumasi

Obenfo Nana Kwasi Gyetuah

GNACOPS-NED