When Ghana’s cedi was in free fall in 2022, the government unveiled an unusual remedy: the gold-for-oil programme.

With the currency tumbling against the dollar and fuel prices surpassing 20 cedis per liter, policymakers sought a way to tackle the root cause—Ghana’s dependence on imported petroleum products that sap its foreign reserves.

The plan seemed straightforward: swap dollars for gold to buy oil, thereby reducing demand for foreign currency and easing the cedi’s decline.

Yet, economic principles and past attempts suggest this might be more a gilded hope than a golden solution. While oil imports can influence exchange rates in the short run, research has shown that their long-term impact on currency value is often limited. This raises the question: Can the gold-for-oil programme truly rescue the cedi from its nosedive, as the government promises?

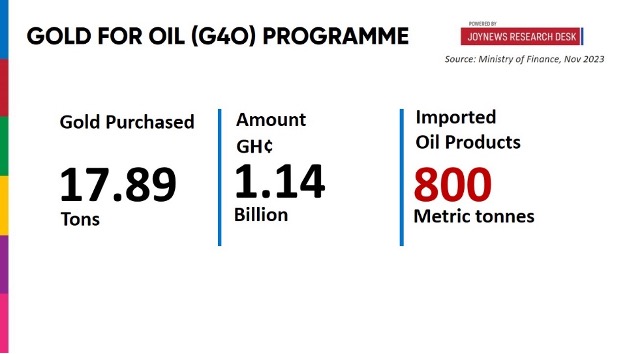

The challenge is substantial. Ghana spends about 400 million cedis monthly on oil imports—a heavy toll on its reserves. The gold-for-oil programme, outlined in the 2024 budget, aims to ease this burden.

However, since its implementation in January 2023, it currently covers only 30% of Ghana’s oil needs—a limited reach that questions its potential impact amid the country’s broader economic challenges.

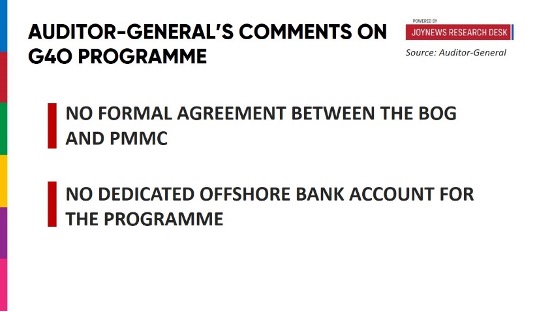

A closer look at the programme reveals structural flaws that cast doubt on its viability. Most notably, there is no formal agreement framework between the Bank of Ghana and the Precious Minerals Marketing Company (PMMC) —a glaring oversight noted by the Auditor-General in a 2023 report.

The Bank of Ghana has since assured that a framework is being finalized and a separate account for Gold-for-Oil transactions will be established.

Moreover, the programme mandates that small-scale miners sell their gold to the state-run Precious Minerals Marketing Company (PMMC). While this could secure a steady gold supply for oil deals, it inadvertently encourages smuggling.

Many miners are locked into forward contracts to deliver gold to foreign buyers at a premium. Forced to breach these agreements due to the government’s directive, some turn to the black market to fulfill their commitments.

What about fuel prices? Evidence thus far is mixed. While prices at Goil stations have shown some stability, the Africa Centre for Energy Policy (ACEP), a think tank, and energy analysts attribute this to favourable global oil market trends, rather than any wizardry from the gold-for-oil scheme. This implies any perceived gains might be more coincidental than consequential.

Meanwhile, the programme’s opacity has fueled political controversy. The Auditor-General’s concerns have been amplified by the opposition National Democratic Congress (NDC), which alleges that the deal is mired in secrecy and pledges to audit it if they win power. The parliamentary minority has demanded further scrutiny, but the government insists the programme is under the Bank of Ghana’s remit, not a typical government initiative.

Despite the controversy, the Gold-for-Oil programme remains a focal point in political campaigns. The current Vice President, who is also a leading candidate in the upcoming elections, has vowed to expand the programme if voted into power. This promise suggests a future where Ghana could increasingly rely on such barter-style arrangements to manage its foreign exchange needs, though it remains to be seen if an expanded programme would overcome the existing challenges or simply amplify them.

Ghana’s gold-for-oil policy, marketed as a daring move to stabilize the cedi, now finds itself ensnared in execution flaws, questionable efficacy, and mounting political discord. As its true impact remains cloudy, the policy may soon join the long list of bold yet faltering attempts to tame Ghana’s turbulent currency.

Source: Caleb Wuninti Ziblim