Six months after Muhammed Yusuf had been sold, tortured and forced to watch as a friend died, he found himself back at the parched, dusty bus station where his ordeal began, facing the man who had made him a slave.

Unembarrassed and unrepentant, the smuggler was still touting for business among the crowds flooding into Agadez, an oasis town on the fringe of the Sahara desert in central Niger that has for centuries been a trading centre and gateway to shifting paths across the desert.

“I told him ‘my friend died in Libya because of you’,” Yusuf said a few days after the meeting. Then, desperately hungry, he asked him for some food. The man shrugged off both appeals, and walked away, saying only: “I am sorry, but God will help you.”

Yusuf, a 24-year-old Nigerian, was one of thousands of people who had travelled to Libya looking for work, or hoping to sail to Europe, who were instead sucked into a grim and violent world of slave markets, private prisons, and brutal forced brothels.

The dangers of attempting to cross the Mediterranean to Europe, in overcrowded, unseaworthy vessels, have been highlighted by a series of desperate rescue missions and thousands of deaths at sea in recent years. Last week, at least 245 people were killed by shipwrecks, bringing the toll for this year alone to 1,300.

Some dead migrants being picked by in body bags on the Spanish shore

Less well-known are the dangers of Libya itself for migrants fleeing poverty across West Africa. The country’s slide into chaos following the 2011 death of dictator Muammar Gaddafi and the collapse of the government have made it a breeding ground for crime and exploitation. Two rival governments, an Isis franchise and countless local militias competing for control of a vast, sparsely populated territory awash in weapons, have allowed traffickers to flourish, checked only by the activities of their criminal rivals.

Last year, more than 180,000 refugees arrived in Italy, the vast majority of them through Libya, according to UN agency the International Organisation for Migration (IOM). That number is forecast to top 200,000 this year – and these people form a lucrative source of income for militias and mafias who control Libya’s roads and trafficking networks.

Migrants who managed to reach Europe from Libya have long told of being kidnapped by smugglers, who would then torture them to extort cash as they waited for boats. But in recent years this abuse has developed into a modern-day slave trade – plied along routes once used by slaving caravans – that has engulfed tens of thousands of lives.

The new slave traders operate with such impunity that, survivors say, some victims are being sold in public markets. Most, however, see their lives and liberty auctioned off in private.

“They took people and put them in the street, under a sign that said ‘for sale’,” said Shamsuddin Jibril, 27, from Cameroon, who twice saw men traded publicly in the streets of the central Libyan town of Sabha, once famous as the home of a young Gaddafi, but now known for violence and brutality.

Some rescued migrants on their way to Italy from Libyan

“They tied their hands just like in the former slave trade, and they drove them here in the back of a Toyota Hilux. There were maybe five or seven of them.”

He was too frightened to speak to the men, who were lined up near a monument known as Dar Muammar, a one-room cabin where Gaddafi had lived as a student. The spot, beside a popular bakery, was apparently chosen for the large volume of potential customers passing by, Jibril said.

Another migrant reported being auctioned off at dusty parking lots on the outskirts of town, after being driven in from Agadez, which has for centuries been a last stopping point for traders, goods and slaves heading into the desert.

Today, it is the most northerly town that West Africans can reach without papers: it is part of the huge Economic Community of West African States, which allows visa free-travel for citizens of the region. That has made it the place where most put themselves in the hands of smugglers, and many get sucked into slavery at the bases of middlemen, known in migrant slang as “connection houses”.

This, according to Jibril, is where the problems start. Some of the victims pay for their journey but are sold off anyway when they reach Libya. Others, like Yusuf, the Nigerian who lost his friend, are told they can travel on credit and pay off the trip by working in Libya. They only find on arrival they have been carried as cargo for sale.

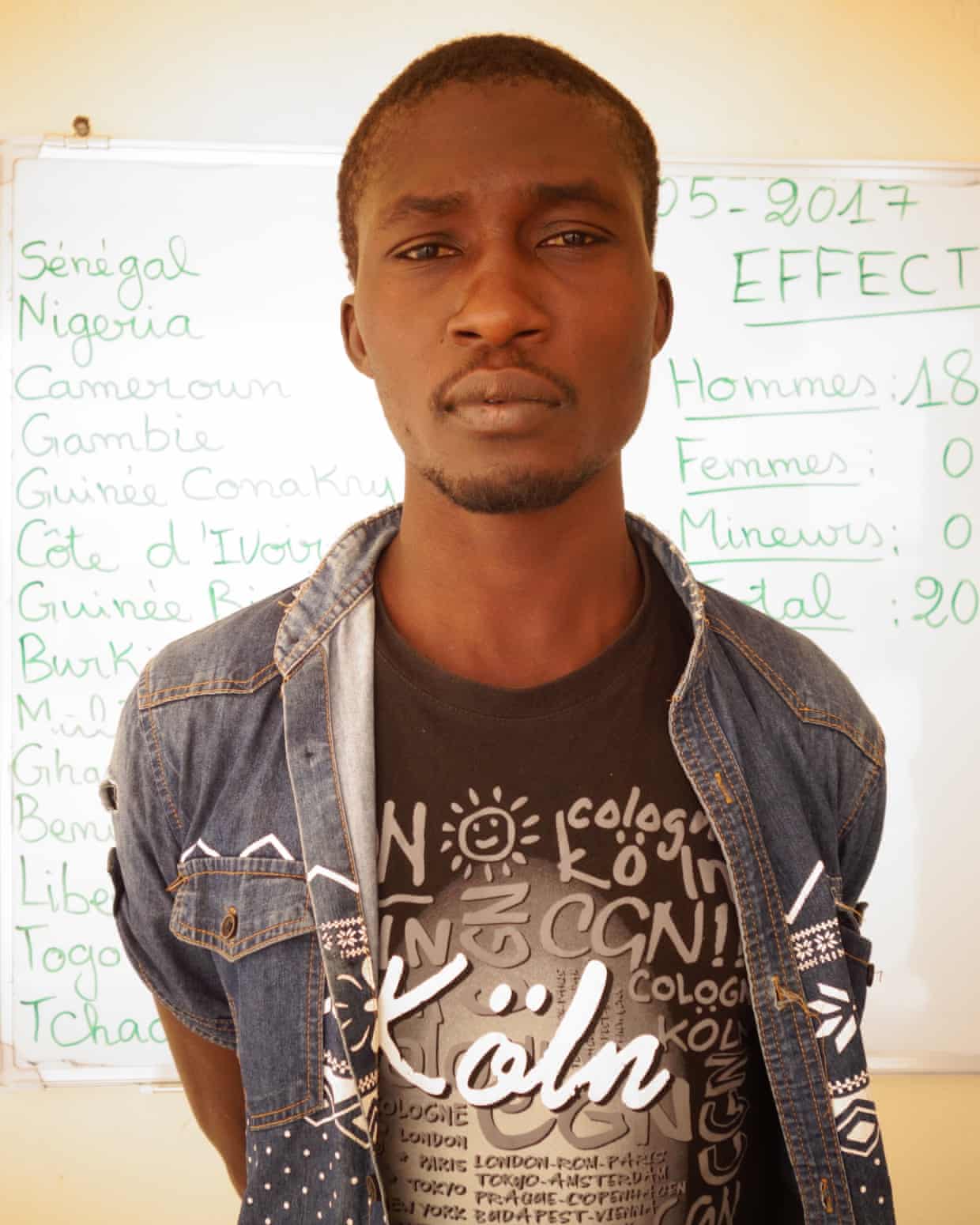

Nigerian Muhammed Yusuf, 24, was sold to traffickers; tortured, forced to watch a friend die.

Adama Isoomah, warned by friends of the horrors in Libya, thought he had paid for a passage to Algeria. There were no signposts in the desert to alert him to the trickery. “I know there is a desert on the way, but I didn’t know what it looked like,” he said. “After four days, they said ‘welcome to Libya’. I said, is this a dream to me or reality? I know this is where they sell people. And then I realised that the middleman had sold me.”

Abahi (not his real name) is one of these modern-day slave traders, though he bridles at descriptions of his trade as trafficking. He shares cheerful selfies taken in the desert with the men he was carrying to market, and even admits to worries about the fate he drove them into. “It’s no good. Now you will see the migrants suffering and say, ‘I am the man who take them in this problem.’ It’s no good. But what can we do? Inside Libya, everything is ruled by the militias.”

He says he would never steal from migrants who paid their fare, but admits that the 27 people who cram into his Hilux for each trip are a mix of passengers and cargo, depending on who is paying. “If you take them for nothing, the boss in Sabha pays,” he says. “It’s around €400 per person.”

An illegal trade in a lawless country, there is no one model for slavery practised in modern Libya, but the shifting forms of trade and business are all united by the misery and exploitation of its victims.

Female migrants are generally sold into sexual slavery, a trade so lucrative it makes them more valuable as a commodity than men. In Sabha, the clearing house and brothel used for trafficking migrant women was well-known, said Fasan Olaside, a 27-year-old Nigerian builder who was himself kidnapped and held for ransom twice inside Libya.

“There is a three-storey building, where the business takes place,” he said. “Immediately, the women enter the building, that is it – they can’t leave. Some are forced to work there; some are sold elsewhere. It looks just like a normal house, but the local citizens know what is happening there. The person who buys them can sell them on for two or even four times as much.”

Prices for women start at 3,000 Libyan dinars, around €2,000 – more than twice as much as traffickers pay for men, said Olaside, who is still horrified by what he saw: “I was wondering how can this be possible. There were slave markets 300 or 500 years ago, but we are in the third millennium now.”

The men’s fates vary more, depending on their skill and who buys and sells them, according to former captives waiting to go home at a centre run by the UN’s International Organization for Migration. It offers free tickets and basic medical help for those on their way to and from Libya who want to return home, and tries to warn migrants of the dangers of the journey.

On a baking May day, dozens of men waiting for their tickets home said they had fled captivity in Libya. They came from countries across West Africa, including Senegal, Guinea Bissau, Gambia, Liberia and Nigeria, and described a system controlled by Libyans, but often run on a day-to-day basis by their fellow countrymen, who had joined the trade or been co-opted as guards.

They said captors looked for skilled tradesmen among new slaves, and sold electricians, plumbers and others to buyers who needed particular trades. The rest were auctioned off as labourers, or often simply held as human bargaining chips. In grim private jails, their captors forced them to call families across West Africa, demanding ransoms of hundreds of dollars.

Those whose families can’t or won’t pay are beaten and tortured, often while smugglers are on the phone to relatives, the cries of agony used to wring out faster payment. “People were tied up like goats, beaten with broom handles and pipes every blessed day, to get the money,” said Isoomah, from Liberia. “If they do not do that, the money will not come.”

A ‘connection houses’ where middlemen put migrants in touch with people smugglers.

Some smugglers are even more notorious. Jibril told of a private house-turned-prison that migrants have nicknamed the house of debt: “Some of them, they cut their fingers off, or brand them with hot iron.” The luckier ones were bought as workers.

The buyers are men like Tukur, a slim man of Nigerien origin, barely five feet tall and with ceremonial scars by his eyes that marked him as a member of the Hausa ethnic group. He paid for Yusuf and his friend and was named by two other migrants held in the city. The smuggler Abahi also said he knew Tukur and had on occasion sold men to him; his general concern for migrants heading to Libya did not cover those he hands over to the diminutive trader.

“Sometimes they say he is not OK, but it is not my problem. I like my money. He pay me and I go. I don’t see what he do. I just like my money and go.”

Tukur was based in Sabha, wore traditional robes and a small cap, and was flanked by two bulky henchmen who enforced his orders with cables, sticks or more vicious weapons, victims said.

“Someone said ‘wait for the man to take you to the bakery’,” Yusuf remembered. He and his friend had paid half their fares and agreed to work on arrival to pay off the second. But their driver stole their savings and sold them both. “I didn’t realise that we had already been kidnapped. Then Tukur arrived with Abdullah and Isa. They read our names off a list of paper: me, Abdullah Bundu – my friend from Sierra Leone – and three others. ‘You didn’t pay, come this way,’ he said.”

Yusuf explained that he and Bundu had paid half, and Tukur invited them into the house for what he thought would be a discussion. Instead, it was the beginning of an ordeal that would cost Bundu his life. “As we entered the building, we heard the lock turning,” he said. Then they said, you should call your family fast and ask for money.”

Bundu died of a heart attack following prolonged beatings, and Yusuf was ordered to help take his friend’s body to the hospital, where doctors accepted without question the captors’ story that the heart attack had been spontaneous.

On the way back, Yusuf decided to risk an escape attempt, convinced that otherwise he, too, would die in the jail, where some had been wasting away on starvation rations for months. There are thought to be thousands of migrants trapped in similar private jails and extortion centres scattered across Libya, where execution and torture are commonplace.

Resting on a clinic bed, his legs swathed in bandages and his skin mottled by burn scars, Couilbaly Yahyah still doesn’t know why his captors decided to burn him alive. After he’d been a captive inside Libya for just three weeks, guards took him into a courtyard and picked up a five-litre jerrycan, whose purpose he understood only when they began splashing fuel over his body.

“They only spoke English, not French, and they were just shouting ‘money, money, money’ at me,” said the French-speaking Yahyah, who comes from Ivory Coast.

Seconds later someone lit a piece of paper and threw it at him. The pain was instant and searing, although he thinks a thick winter coat he was wearing offered a little protection. Screaming he raced around the courtyard in a crazed bid to escape the blaze, until one of the men took pity on him.

“When I was running around in flames, a guard came over and ripped off my coat, tearing it in two, and put out the fire. Without the coat and the guard, I would be dead.”

Terribly injured and wearing only his underwear, the 24-year-old was thrown out into the street to die, but saved by a passing African migrant, who took him to the hospital.

Months later the burns have left a pattern of scars on his hands and welded his left knee into a permanent crook. Both his legs are still wrapped in bandages, and he lies on a clinic bed in northern Niger with months of slow healing ahead, dreaming of the day he can go home.

“I just want to go home and see my daughter Khadija,” he says, showing a picture of a smiling toddler on his phone. She was just a few months old when he left. He had paid for a passage to Italy but was abandoned in Sabha.

“We called the smuggler from inside Libya and said ‘we are here’, but he just told us ‘I’ve spent too much on you. You should call your parents and ask for money’,” he said. “It turned out it was all a lie: he didn’t have another connection to take us to Italy.”

With no money to continue to Europe or return home, he was seized by a gang while looking for work to pay for passage either onwards or home.

The country director for the UN’s migration agency in Niger has spent years working with victims of some of the world’s most abusive and distressing trafficking networks, but found the stories coming out of Libya “shocking”.

“I think the conditions are getting worse,” Giuseppe Loprete told the Observer. “What migrants are telling us deserves our highest attention. This violence against vulnerable human beings whose only fault is dreaming about a better life is unacceptable.”

A crackdown by the Niger government has choked off much of the trade in Agadez, where it was once carried out almost openly. Dozens of smugglers are in jail, hundreds of vehicles have been confiscated, the cost of bribing checkpoint guards has soared, and fewer migrants arrive or leave.

But that is only a very temporary solution to a problem driven by desperate poverty and wild dreams that the horrors of Libya cannot yet overshadow.

The IOM is helping those who return from Libya share stories of the horrors that await there. The migrants are all desperate to spare others their fate. “If I meet someone at home who says they want to go to Libya, I will slap him,” said Isoomaah.

But in the “ghettos” of Agadez, dozens of others are still waiting for their call to the desert, buoyed by their dreams and convinced that they are smart enough to escape slavery.

“Those who say they will take you for free, they will sell you. So if we don’t have money, we will not go,” said Paaliou Jobe, a 30-year-old Gambian who is living in a half-built house in the town with six countrymen, the youngest of them only 16.

And he added: “If you have a bad connection man, you are sold. If you have a good connection man, you are safe. We want to go. That is our dream.”