One player was a notable absentee during Zambia’s first two games at the 2023 Africa Cup of Nations, but Enock Mwepu’s non-selection had nothing to do with his abilities.

Instead, it was because the midfielder, who captained his country in their first two qualifiers in June 2022, had been forced to retire from football after being diagnosed with a hereditary cardiac condition.

In September that year, he had fallen ill in Mali with tests upon his return to his then club, Premier League side Brighton, delivering the worst outcome for the then 24-year-old.

The Seagulls said Mwepu would be at an “extremely high risk of suffering a potentially fatal cardiac event” if he continued playing.

“It is a terrible blow for Enock, but he has to put his health and his family first,” Brighton’s head of medicine said at the time.

“This is the right choice, however difficult it is to quit the game he loves.”

Yet it is not a decision that all African footballers in Mwepu’s position have made.

Just two months ago, former Ghana international Raphael Dwamena died after collapsing on the pitch in Albania, having chosen to play on after removing an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), fitted in 2020, that could have prevented his fatal heart attack.

Manchester United midfielder Christian Eriksen had a similar device fitted after collapsing while playing for Denmark at Euro 2020.

One of Dwamena’s former clubs, FC Zurich, first discovered his heart issues in 2017 and were advised by various specialists and cardiologists that he could continue – which he did – with the Swiss Super League side always ensuring they had a mobile defibrillator pitch-side in case of emergency.

But there was no such provision at Albanian side Egnatia FC, who were contacted in vain by the BBC but who told the Athletic last year that they were happy for Dwamena to play “so long as all the tests were done by the club”.

Knowing the risks

Sadly, the former Black Stars striker was not the only African to die on the pitch last year.

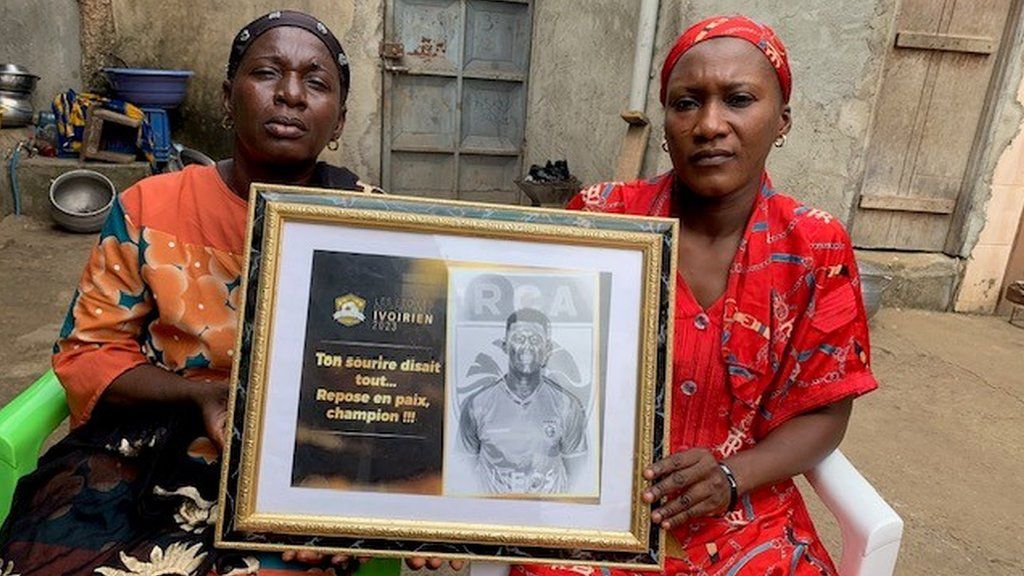

Moustapha Sylla passed away in March last year while playing for top-flight side Racing Club d’Abidjan in Ivory Coast, the country currently hosting the ongoing Africa Cup of Nations.

Like Dwamena, Sylla would also have been aware he was risking his life by taking to the field, as the defender had been effectively kicked out of the Malian league in 2022 after mandatory pre-season medical checks revealed his condition.

His death, aged just 21, prompted former Ivory Coast captain Didier Drogba to issue a plea on behalf of all players in his homeland’s local league system after its third heart-related death since 2019.

“Condolences to Ivorian football… 3 deaths of players in the Ivorian pro league in less than 4 years…,” Drogba posted on X, then known as Twitter., external

“When will there be compulsory medical examinations for “professional” players?… Blood test, ECG [Echocardiogram], stress tests? When will sports medicine arrive?”

With at least two dozen African footballers known to have died of heart-related issues over the years, Drogba’s attitude about needing more stringent medical provisions for cardiac issues is one with which another ex-Chelsea star agrees.

“I played in Europe several times and I know that when you sign the contract, you have to pass a medical control,” said Geremi, a former Cameroon international who is now a players’ union representative.

“We have to implement that here in Africa.”

While this does happen in some African clubs, it does not happen all over – one reason for Drogba’s plea.

Like Geremi, who lost team-mate Marc-Vivien Foe on the pitch in 2003, Drogba also lost an international team-mate to a heart issue in Cheick Tiote, an African champion in 2015 and a man with whom he shared the pitch on dozens of occasions.

Listening to the medics

One major issue is that the African heart is believed to be more susceptible to cardiac problems, with a medical research team backed by world governing body Fifa determining, in 2009, that “black African athletes seem to have an increased risk of adverse cardiac events during sports events”.

The other primary issue is the refusal of some players with heart issues to heed medical advice.

South African doctor Lervasen Pillay is someone who knows this only too well, having had to advise five different footballers to quit because of heart-related problems.

“It’s never an easy conversation, because someone has been doing this job for 10-15 years and now you’ve given him news to say, ‘Listen, you can’t do this anymore, you need to make a plan B’,” Dr Pillay told BBC Sport Africa.

“Most footballers have not established a Plan B by the time they’re 25, and the conversation often boils down to that exact question: ‘What am I going to do if I stop playing football?’

For Dr Pillay, it is hard to watch when players who have been told not to play stick to Plan A despite knowing the dangers.

“When you see the guy’s name on the starting line-up you cringe – and if it’s going to be a televised match, I’ll change the channel,” he said.

One patient, who cannot be named without breaching confidentiality rules, died two years after he failed to heed Dr Pillay, leaving the latter “depressed for a while”.

“If you find someone with a cardiac problem, then ensure your medical care around that – so (that) you have things like automatic external defibrillators around, access to hospitals and emergency vehicles, because if you don’t have them, you are creating a problem.”

While FC Zurich took precisely that action in relation to Dwamena, many other clubs have not.

There have been notable incidents in the past where basic medical provisions are not available in African grounds, such as when local Nigerian footballer Chineme Martins died in 2020 following a catalogue of failures.

Access to the right support

In a bid to reduce the number of tragic incidents that have rocked the sport, the Confederation of African Football conducts mandatory tests before major international tournaments, as does Fifa.

Fifa recommends that every school, club and organisation involved in football has an emergency plan in place to deal with a collapsed player.

Following Sylla’s death, his sister Bintou Sylla told BBC Sport Africa that the medical support given to her brother following his collapse was inadequate.

Both Racing Club and the Ivorian football federation did not respond to the BBC’s requests to comment on Sylla’s death and its surrounding factors.

He died at the Robert Champroux Stadium in Abidjan, Ivory Coast’s largest city which is hosting matches in two different stadiums – the Felix Houphouet-Boigny and the Alassane Ouattara – during the Nations Cup.

But in contrast to local Ivorian league matches, there is plenty of medical support provided during Africa’s biggest sporting event, with pitch-side care as well as ambulances, helicopters and nearby hospitals all on standby.

Some see a clear contrast between the way in which international and local players are looked after.

“They must have access to the same medical support,” Bintou Sylla said. “Because it is the lives of children that are in play here.”

“So they really must review the medical assistance in Ivorian clubs. We don’t need another player to suffer.”

Given the heartbreak suffered by so many, Mwepu – who may be finding it difficult following Zambia’s progress at their first Nations Cup finals since 2015 – can at least take solace in knowing that, however hard his decision to quit, it is one that could well have saved his life.

2023 AFCON: They are scammers – Former Okwawu United coach slams Black…

2023 AFCON: I take full responsibility – Chris Hughton breaks silence…