Indian billionaire Gautam Adani has sought to reassure investors after his company pulled a surprise by calling off its share sale.

On Wednesday, Adani Enterprises said it would return $2.5bn (£2bn) raised from the sale to investors.

The decision will not impact “our existing operations and future plans”, Mr Adani has said.

The move caps an eventful week which began with a US investment firm making fraud claims against Adani group firms.

Adani denies the allegations.

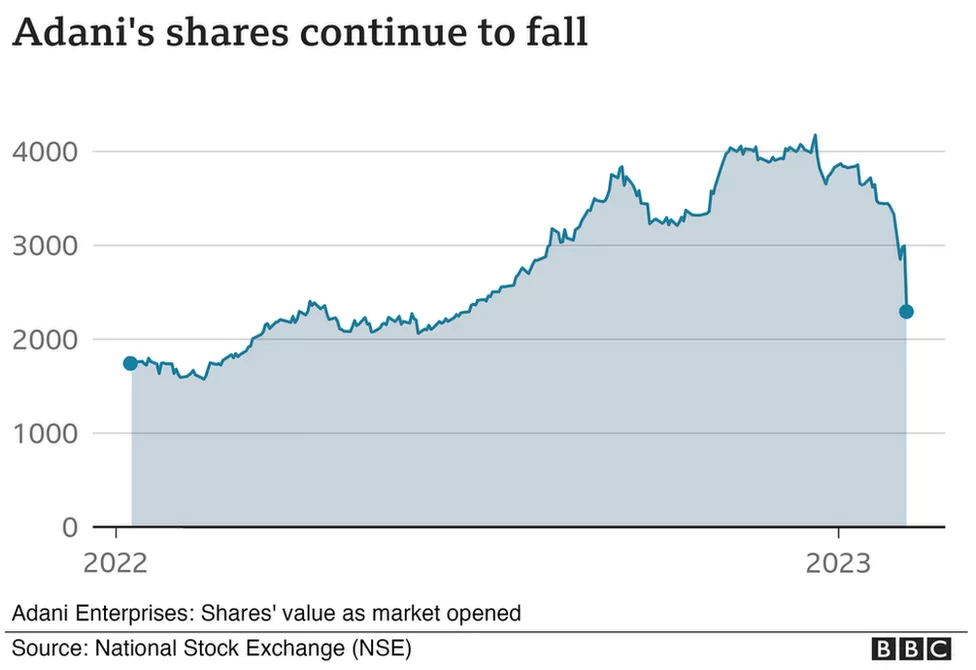

But the group’s companies have seen $108bn wiped off their market value over the past few days.

Mr Adani himself has lost $48bn of his personal wealth and is now 16th on the Forbes real-time billionaires list.

How did this happen?

Less than two weeks ago, Mr Adani was the world’s third richest man.

Shares of Adani Enterprises, the flagship company of his port-to-energy conglomerate, were due to go on sale on 25 January in India’s largest-ever secondary share offering.

But a day before that, US-based investment firm Hindenburg Research published a report accusing the Adani group of decades of “brazen” stock manipulation and accounting fraud.

Hindenburg specialises in “short-selling” – betting against a company’s share price in the expectation that it will fall.

The Adani group responded by calling the report “a malicious combination of selective misinformation and stale, baseless and discredited allegations”, but that wasn’t enough to stem investor fears.

Mr Adani’s group has seven publicly traded companies which operate across a wide range of sectors, including commodities trading, airports, utilities, ports and renewable energy. Many Indian banks and state-owned insurance companies have either invested in or loaned billions of dollars to companies linked to the group.

Was that all?

No. As the market rout continued, the Adani Group issued a detailed rebuttal – running into more than 400 pages – and called the Hindenburg report a “calculated attack on India”.

It said that it had complied with all local laws and had made the necessary regulatory disclosures. It also accused the report of being intended to enable Hindenburg “to book massive financial gain through wrongful means at the cost of countless investors”.

Hindenburg, however, stood by the report and said that the Adani Group had “failed to specifically answer 62 of our 88 questions”.

What was the market’s reaction?

When the Adani Enterprises share sale began on 25 January, it received a muted response. Only 3% of its shares had been subscribed by the second day as retail investors stayed away.

But foreign institutional investors and corporate funds supported the group – on 30 January, Abu Dhabi’s International Holding Company, backed by a member of the UAE royal family, invested $400 million in the share sale.

In a last-minute push, Indian tycoons Sajjan Jindal and Sunil Mittal also subscribed to the share sale in their personal capacities, Bloomberg reported.

Analyst Ambareesh Baliga told Reuters after the share sale that the group had been unable to fulfil its aim to “broadbase the shareholding”.

Shares of the group’s various companies also continued to fall.

So what’s next?

Reports by Reuters and Bloomberg say that India’s central bank has asked the country’s lenders for details of their exposure to the group.

In his statement to India’s exchanges, Mr Adani said, “Our balance sheet is very healthy with strong cashflows and secure assets, and we have an impeccable track record of servicing our debt.”

But Edward Moya, an analyst at brokerage OANDA, told Reuters that the withdrawal of the share sale was “troubling” because it was “supposed to show the company is still believed in by its high net-worth investors”.

American investment bank Citigroup’s wealth arm has stopped accepting securities of the Adani group as collateral for margin loans while Credit Suisse has stopped accepting the group’s bonds. Ratings agency Moody’s unit ICRA has said it was monitoring the impact of recent developments on Adani Group stocks.

But Vinayak Chatterjee, founder and managing trustee of the Infravision Foundation, was optimistic, calling the current situation “a short-term blip”.

“I have observed this group for a quarter century as an infrastructure expert. I see varied operating projects from ports, airports, cements to renewables which are solid, stable and are generating a health cash flow. They are completely safe from the ups and downs of what happens in the stock market,” he told the BBC’s Arunoday Mukharji.

However, Hemindra Hazari, an independent research analyst, said that he was surprised that “we haven’t heard anything from the market regulator SEBI or the government till now”.

“They should have spoken out to soothe the nerves of investors,” he told the BBC.

The issue has also set off a political row.

Mr Adani is perceived as being close to Prime Minister Narendra Modi and has long faced allegations from opposition politicians that he has benefited from his political ties, which he denies.

On Thursday, opposition parties demanded a discussion in parliament about the risk to Indian investors from the fall in Adani company shares. They have also asked for an investigation into Hindenburg’s allegations.