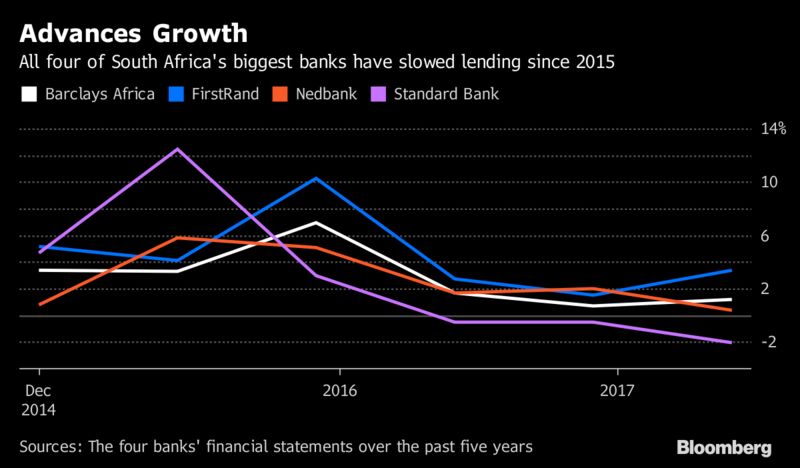

South Africa’s four biggest banks, pummeled by political wrangling and enmeshed in the country’s economic malaise, are increasingly shying away from their main role: lending.

“Credit extension is going to be low for the next two to three years, unless we see some real recovery in economic growth,” FirstRand Ltd. Chief Executive Officer Johan Burger said by phone from Johannesburg on Thursday. “South Africa’s growth prospects remain weak and uncertain.”

Banks are reining in lending as President Jacob Zuma’s administration struggles to reignite growth in the continent’s most industrialized economy and cut unemployment, which has reached a 14-year high. Business confidence is at its lowest level since 1985 in the wake of efforts to diminish the central bank’s independence, eight failed opposition attempts to unseat Zuma and confusion over new mining rules.

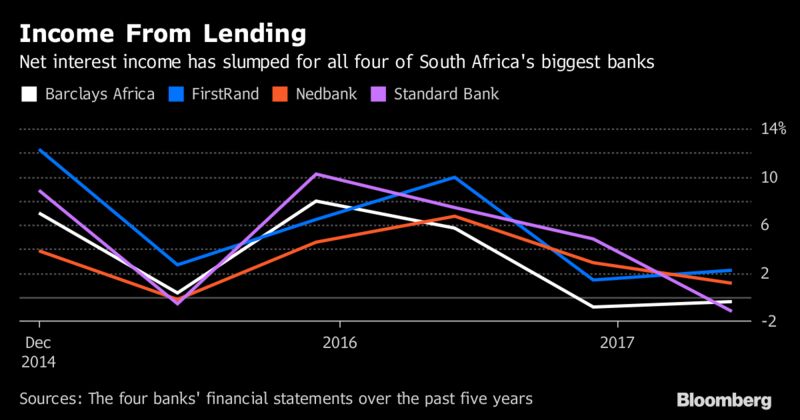

FirstRand, the continent’s largest lender by market value, on Thursday reported net interest income growth of 7 percent for the 12 months through June compared with an increase of 18 percent in fiscal 2016. Standard Bank Group Ltd., Barclays Africa Group Ltd. and Nedbank Group Ltd. all published first-half results in August that showed a similar pattern. While earnings are still increasing, helped by cost-containment and lower impairments, it’s getting tougher to keep the momentum going.

Increases in revenue will be muted over the next 12 months as lending slows, said Adrian Cloete, banks analyst at PSG Wealth in Cape Town. While the lenders aren’t expected to slump into losses, earnings growth will be “at a lower rate than the last few years,” as improvements made in bad debts turn into a “headwind,” meaning costs will have to be reduced, he said.

FirstRand doesn’t expect to see improvements in impairment levels and is focusing on expanding smaller parts of its business like insurance and investment management to diversify earnings, the CEO said. “When you don’t have a lot of top line growth, cost management becomes critical.”

A 25 basis-point interest rate cut by South Africa’s central bank in July won’t be enough to kick start a big improvement in lending, Burger said. That month, policy makers reduced the benchmark rate for the first time in five years, projecting the economy will expand 0.5 percent in 2017.

S&P Global Ratings and Fitch Ratings Ltd. cut the nation’s foreign-currency credit rating to junk in April after the president fired his respected finance minister and replaced him with someone with no financial experience. A succession battle within the ruling party over who will succeed Zuma as president of the African National Congress in December has also spurred infighting and hindered the delivery of government services.

It’s only a matter of time before local-currency debt is slashed to junk, according to Adrian Saville, chief executive officer of Cannon Asset Managers in Johannesburg, which will further burden the banks as their cost of funding rises.

To counter that FirstRand is going to “try and pierce the sovereign ceiling” by building access to offshore funding so it doesn’t need to rely on the South African government’s credit rating, Burger said. For confidence and growth to return, the country needs ethical leadership, policy certainty, and careful fiscal management, while issues such as the skills shortage, improving education and making it easy to do business also need to be addressed, he said.