The World Bank estimates that $4 billion worth of remittances flowed into Ghana’s economy between 2016 and 2022.

This makes forex inflows from remittances the highest compared to cocoa, oil and even gold if receipts are seasonalized to factor in the true amount surrendered.

To test the importance of remittance inflows to the Ghanaian economy, it is essential to consider the Bank of Ghana’s statements in its 2023 audited report on inward remittances and their role in economic stability.

First, the bank disclosed that “in the foreign exchange market, the Ghana cedi remained relatively stable against the major trading currencies in 2023. This was due to improved inflows from the first tranche of the IMF ECF, the domestic gold purchase programme, remittances, and FX purchases from mining and oil companies, as well as tight monetary policy.”

Secondly, it stated that Ghana’s income account in 2023 “registered a lower deficit of US$2.08 billion in 2023, down by 53.8 per cent from US$4.51 billion in 2022. Current transfers, largely comprising private remittances, recorded a net inflow of US$3.93 billion in 2023, compared with US$3.57 billion net inflow in 2022.”

Finally, it dropped a bombshell that “in 2023, 11 licensed FinTech companies provided inward remittance service to customers. The total value of remittances received in 2023 was GH¢57 billion, compared to GH¢18 billion in 2022.

The remittance space, over the years, has seen licensed FinTechs providing innovative solutions, hence the immense growth witnessed in the review year.”

The reason why this is a bombshell is that the Bank of Ghana failed to disclose the foreign exchange equivalent of these remittances as required by the International Accounting Standard 21 (IAS 21), which outlines how to account for foreign currency transactions and operations in financial statements, and also how to translate financial statements into a presentation currency.

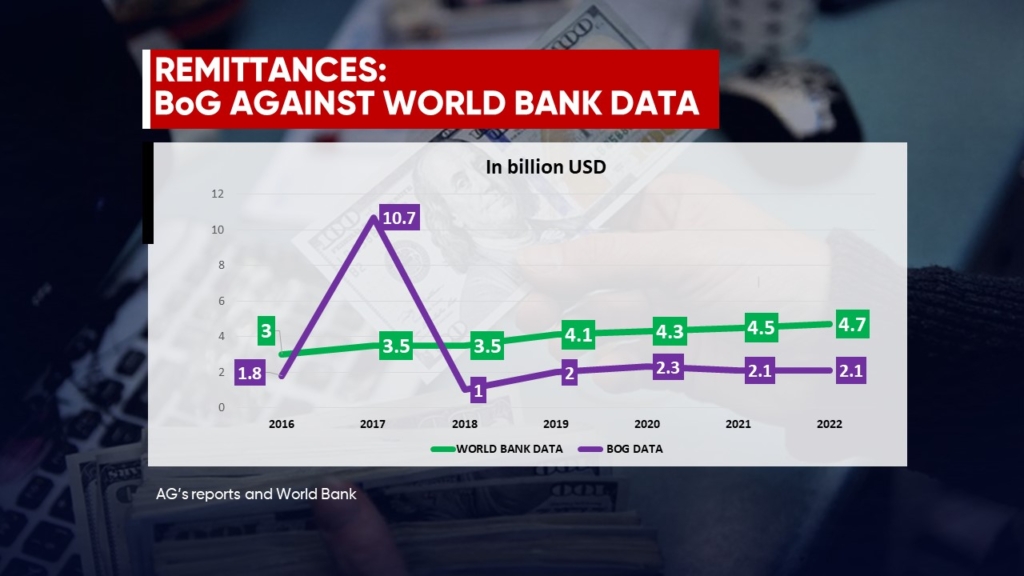

Over the past eight years, available data from the World Bank and the Bank of Ghana have contrasted each other.

While the World Bank recorded a total of $27.6 billion as remittances inflow to Ghana from 2016 to 2022, the Auditor General’s reports on the Bank of Ghana’s consolidated statements of foreign exchange receipts and payments within the same period accounted for only $22 billion, leaving a gap of some $5.6 billion. The key question is where did these inflows from remittances go?

Now, with the central bank’s latest admission that FinTechs in 2023 facilitated remittances amounting to GH¢57 billion, compared to GH¢18 billion in 2022, we ask if the previous gap in reporting between the Bank of Ghana and World Bank could be attributed to remittance inflows passing through FinTech and other platforms rather than the 23 dealer banks. This consideration is especially pertinent given that this is the first time within the period under review that the Bank of Ghana is reporting on remittance inflows in its annual audited reports.

The eleven Fintech companies are withholding approximately GHC57 billion equivalent of US$ 5 billion of foreign currencies from inward remittance in 2023 and held additional GHC 18 billion an equivalent of US$ 3 billion in 2023 in contravention of the Foreign Exchange Act 2006 Act 723 Section 15 Subsections 1 to 4 respectively.

This major discrepancies between the 23 authorized dealer banks licensed under Foreign Exchange Act 2006 Act 723 and the newly Money Transfer Companies and 11 Fintech Companies have played a major role in the persistent depreciation of local currency against the major trading currencies.

It is estimated that the country has lost nearly US$ 8 billion over the past two years in the foreign remittance space. It outlines discrepancies in this existing framework as well as the need for additional data from new MTOs and Fintech companies to address the anomalies identified in the World Bank data on inward remittances and that from Bank of Ghana’s data from the 23 authorized dealer commercial banks over the period 2016-2023.

OVERVIEW OF MONEY TRANSFER COMPANIES AND FINTECH COMPANIES IN THE INWARD REMITTANCE SPACE IN GHANA

Money transfer companies (MTCs) and financial institutions were the two central means of transferring and receiving cash in Ghana before 2019 where the Government passed the Payment Service and System Act 2019 Act 987 whereby new Money Transfer Companies and Fintech Companies into inward remittance space.

Through their global networks, these institutions have provided avenues for diaspora communities to remit money to Ghana.

They offered a variety of delivery service channels, such as direct-to-account, cash to the mobile phone, cash-to-card, and person-to-person transfers. Their platforms are integrated to allow money transfers from bank to bank, from MTCs to bank, and through a mobile money system. According to World Bank data on inward remittance, Ghana has witnessed a substantial rise in remittances inflow from US$2 billion in 2014, US$5 billion in 2015, US$3 billion in 2016, US$3.5 billion in 2017 to US$4.5 billion in 2021 and further to US$4.7 billion in 2022; US$ 5.2 billion (World Bank 2023).

The Bank of Ghana’s estimates of the balance of payments suggested that remittances place second after exports in terms of resource inflow in Ghana. The IMF balance of payments indicators in 2016 report that Ghana’s inward remittance receipts from the rest of the world for the past decade averaging US$2.9 billion per year far exceeding the surrendered gold proceeds from mining companies of US$863,356,251.30 and US$990,172,984.99 recorded in the years 2021 and 2022 respectively.

Data from the AG reports shows a clear upward trend in the amount of inward remittances over the years. The total amount has consistently increased from 2016 to 2022, indicating a positive trend in the influx of foreign funds. The most significant change occurred in 2017 when there was a substantial jump in inward remittances, increasing from US$1,837,506,014.80 in 2016 to US$10,766,037,529.00 in 2017.

This enormous increase is a notable outlier in the dataset and should be investigated further. In 2018, there was a decrease in inward remittances to US$1,021,916,059.59, which is significantly lower than the previous years. However, in 2019, the amount rebounded to US$2,005,542,497.90. These fluctuations might be indicative of changing economic conditions or due to the passing of the Payment Service and System Act 2019 Act 987 that which allowed the Fintech Companies in the Inward remittance space since 2019. From 2020 to 2022, there is a consistent increase in inward remittances, with amounts of US$2,310,586,691.47 in 2020, US$2,110,512,179.69 in 2021, and US$2,121,081,266.78 in 2022. This demonstrates stability and growth in remittances during this period, but the inward remittances have declined considerably to compared to World Bank data on inward remittances.

The declined in Ghana’s inward remittances had been validated by the Bank of Ghana that the newly licensed Money Transfer Companies and II Fintech Companies have withheld approximately GHC 18 billion (US$ 3 billion) in 2022 and GHC57 billion equivalent of US$ 5 billion in 2023 at the expense of the country foreign currency reserves. The country has lost approximately US$ 8 billion in the past two years which could have been used to shore up the persistent depreciation of the local currency against the major trading currencies.

However, World Bank remittance reports on Ghana from 2010 to 2022 showed marked discrepancies between their reports and the Bank of Ghana’s annual remittance reports recorded on Balance of Payments (BoPs). US$0.14 billion in 2010; US$2.1 billion in 2011; US$2.2 billion in 2012 ; US$1.9 billion in 2013; US$2 billion in 2014 ; US$5 billion in 2015 ; US$3 billion in 2016 ; US$3.5 billion in 2017 ; US$3.5 billion in 2018; US$4.1 billion in 2019; US$4.3 billion in 2020 ; US$4.5 billion in 2021 ; US$4.7 billion in 2022 and US$ 5.2 billion in 2023.

FINDINGS ON METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES IN ACCOUNTING FOR INWARD REMITTANCES IN GHANA’S B.O.P

Estimates on inward remittance in the B.O.P were based on statistics compiled at the back of the returns of 23 authorized dealer commercial banks on inward remittance submitted yearly. The data obtained and reviewed from the Bank of Ghana’s consolidated statements of Foreign Exchange Receipts. Statistics are provided on a monthly basis, and the aggregation of such flows from all the institutions provides an estimate of inward unrequited transfers.

The main source of data for this item in the BOP was derived from the banks and non-bank financial institutions, which operate money transfer schemes, and the level is the aggregate as reported. On receipt of the submitted data, the staff examines the plausibility of the estimates and where there is a need, the staff follows up with the reporting institution to validate the reported numbers.

One of the major methodological issues was on the compilation and analysis as we observed major discrepancies between the World Bank data on international remittances and that of the Bank of Ghana data on inward remittances as captured on consolidated foreign exchange receipts yearly to the balance of payments data, total inward remittances to the Ghanaian economy ranged between US$2,005,542,497. 90 in 2019 and US$2,121,081,266.78 million in 2022.

The study noted major discrepancies between the Bank of Ghana’s inward remittance returns as part of foreign exchange receipts and the World Bank’s inward remittance reports over the period under review. The low returns on inward remittances for the past four years could be attributed to the newly Money Transfer Companies and 11 Fintech companies that were licensed to operate in the foreign remittance space. Ghana as a country has not been reaping the benefits of more Ghanaians working abroad.

The question that Ghanaian populace wants to know why the country operate two separate foreign exchange systems where the 23 authorized dealer banks accounts for all foreign exchange received from inward remittances while the newly Money Transfer Companies and Fintech companies do not account for all foreign exchange receipt from inward remittances under Foreign Exchange Act 2006 Act 2006?

Over the past seventeen years, the 23 authorized dealer commercial banks’ inward remittance returns were required to be submitted in compliance with the Foreign Exchange Act 2006 Act 723. Over the years, authorized dealer banks and Money Transfer companies (MTCs) and banking agents have facilitated funds transfer from abroad to beneficiaries in Ghana, which were accessed largely through banking halls with the benefit of the foreign currencies being held in local banks’ Nostro account with overseas correspondent banks.

Mobile money and other digital channels that have been made available by payment service providers are now providing extensive, affordable, convenient, and flexible alternative means for accessing remittances by beneficiaries but foreign exchange components could not be traced and tracked to the local banks’ returns or the Bank of Ghana’s nostro balances with their correspondent banks.

Bank of Ghana had previously traced in the international has shown that Inward remittances from Western Union, MoneyGram, Ria Money Transfer and MTOs international remittances through the individual local banks that used the foreign exchange to supplement the foreign currencies for their customers’ import businesses. From previous practices, the local banks then submitted inward remittance returns and their usage of foreign exchange to the Bank of Ghana monthly so that they could capture international remittances in their consolidated foreign receipts.

However, after a careful review of the Bank of Ghana’s operational guidelines issued in 2021 for inward remittance services by payment service providers such as MTOs and Fintech companies were supposed to operate two accounts (a) remittance inflow settlement account and (b) local settlement account without considering reimburse Nostro accounts for which the MTOs and Fintech companies for the foreign exchange.

The current practice has been operated by the Bank of Ghana, the country has not been benefiting from foreign currencies, as the MTCs and Fintech companies are holding foreign currencies in their correspondent banking accounts. Also, after careful examination of the Bank of Ghana’s consolidated foreign receipts on the Balance of Payment data from 2019 to 2023, we noted that there had been no recording, tracking and tracing of the inward remittances in the Bank of Ghana’s consolidated foreign receipts.

The Foreign Exchange Act of 2006 (Act 723) prohibits outbound remittances from Ghana unless the transaction is made through a bank while the same Act 723 prohibits inbound international remittances not made through an authorized dealer bank. The deregulation of foreign remittances had impacted negatively on the stability of the local currency and accelerated the depreciation of the Cedi after the country was barred from the international capital market in 2022.

Today, international remittances which represented the largest source of external finance for Ghana bigger than cocoa and gold over the past years, could have been significantly used to mitigate against persistent depreciation of the local currency against the major trading currencies. The approximate amount of US $ 3 billion in 2022 and US$ 5 billion in 2023 were far more exceedingly above the IMF loan of US$ 3 billion.

Given the enormous volume of remittances transferred to the Overseas from its Ghanaian workers, savings from reduced remittance costs could be recycled into the local economy and spur greater growth. Various research studies have shown that international remittance flows could lead to currency appreciation as well as improving country’s foreign exchange reserves.

Second, the methodological issue was about the compilation and analysis of inward remittances about the current different channels posed different challenges to the Bank of Ghana as the compiler and the ease with which data may be obtained from these various channels depends on the institutional and foreign exchange environment governing remittance transactions and data compilation.

The fact that remittances are transmitted through different channels makes it difficult to capture the full amount in the balance of payments statistics of the recipient country, which tends to underestimate the actual flow of remittances.

The non-compliance with the Foreign Exchange Act 2006 Act 723 by the Digital technology infrastructure companies including the Fintech and Block Chain companies have hindered the regulation of some entities and by extension reporting of remittance data. Still, there is sometimes an overlap of responsibilities between government institutions with poor coordination thus data reported are divergent leaving the compiler and analyst confused. In addition, a clear assignment of responsibility is necessary to know which agency is to generate remittance statistics whether the Bank of Ghana, authorized dealer commercial banks or the National Bureau for Statistics.

Third, the methodological issue noted was the lack of proper attention to remittance statistics have emanated from the inability of most developing countries such as Ghana to develop an appropriate framework for tapping the potential of remittances for growth and development. In addition, most of the MTCs and Fintech don’t have their outlets for remitting monies but rather use the platforms of banks. This adds to the cost of remittances thus discouraging remitters from using formal channels and preferring to go through informal channels.

Fourth, another methodological issue was the low Capacity in BOP Compilation especially in Developing Countries like Ghana accounted for the low recording of inward remittances as compared to the World Bank data on inward remittances.

Due to the complications in compiling BOP numbers, several developing countries are yet to fully migrate to the use of BPM6. Nigeria, for instance, is still using BPM6 alongside BPM5 in carrying out its analysis. The use of different approaches to compilation renders it hard to compare remittances across countries. This problem will be accentuated with the move to BPM7 when several countries are still struggling to migrate fully to BPM6.

Fifth, methodological compilation and analysis issue has been complicated by the licensing of more Fintech companies by the Bank of Ghana in the international remittance space since the passage. Payment Systems and Service Act 2019, Act 987 without taking into cognizance of the existing Foreign Exchange Act 2006, Act 723 might have contributed to major discrepancies between the World Bank data on international remittances and Bank of Ghana data for remittance.

The growing need for safer, more secure and quicker international money transfers has increased the need for digital payments and receipts globally. Digital currencies offer an obvious advantage for remittances as an alternative to the expensive and burdensome money transfer system currently available without considering the treatment of foreign exchange components. However, the low level of financial inclusion and the cyber security threats digital currencies are exposed to invigorate the reluctance with which regulatory authorities are willing to accept the use of digital currencies within their ambit.

Sixth, with increase in the remitting channels has created difficulties for the Bank of Ghana in the capturing of remittance statistics data. Remittance transaction channels are wide and varied and the choice of channel depends on a number of factors including the cost of sending money abroad, speed of delivery, information technology infrastructure at the senders and receivers’ locations, hidden costs in foreign exchange transactions, safety of the funds and so on.

Compilers like the Bank of Ghana of inward remittance statistics might however, find it difficult to know all sources especially the informal sources through which remittances are sent. Remittance service providers are also quite innovative and new transaction channels are being developed consistently without considering the ownership of foreign exchange under existing Foreign Exchange Act 2006, Act 723. Many money transfer businesses in all parts of the world are often not registered or licensed and are not subject to any form of regulation. Reliable data and information on these channels are often lacking making it hard to track remittances through these channels

The final methodological issues in compilation and analysis are the weaknesses in the country’s remittance data (including an assessment of World Bank discrepancies in remittance aggregates) and the need for specific practical guidance on data sources and compilation methods.

The inadequacy of practical compilation guidance concerns compilers, who, as a result, often produce data that is less credible than other balance of payments components. Not all funds remitted by migrants will be recorded as remittances in the balance of payments framework. This sometimes contributes to the data users’ problems in identifying the data that corresponds to their analytical needs.

Hence, the Balance of Payments Textbook states that “money remitted by a migrant to deposit in his or her account with a bank located abroad represents a financial investment rather than a transfer” and is therefore not a remittance (but is instead recorded as an investment asset of the sending economy).

It involves a quid pro quo since the sending party acquires a claim against the deposit-taking bank abroad. Similarly, money remitted to purchase real estate or acquire control of a business would be treated as a form of investment, even if family members in the country of origin live in the house or work in the business.

CONCLUSION

It is important to address policy issues that impact remittances to maximize their impact on savings, investment, poverty reduction as well as the foreign exchange components of the inward remittances. The relevant policy questions are how to leverage the capital potential of remittances, through the improvement of foreign exchange.

Bank of Ghana must ensure there are strategic alliances between banks and Fintech companies and between Ghanaian banks and their correspondents. There is an urgent need to enhance the linkage between money transfer companies, Fintech companies and the rural bank network to track and trace the foreign exchange components of inward remittances.

Bank of Ghana must ensure total compliance with the Foreign Exchange Act 2006, Act 723; AML Act 2020, Act 1044; and Anti-Terrorism Amendment Act 2014, Act 875 to ensure the continuous remittance flows to support the foreign exchange.

Inward remittances remain a stable and sustainable source of foreign exchange earnings too huge to be ignored because inward remittances have contributed to the country’s foreign exchange more than cocoa and surrendered gold proceeds over the past decade. Its benefits far outweigh the few disadvantages that have been pointed out.

On the whole, remittances could salvage a whole family, community, or economy if used for the right purposes. Being able to correctly identify the channels through which remittances flow and converting them to productive uses through formalisation of remittances and proper financial literacy could boost the economy and must therefore be pursued vigorously. This implies that regulatory agencies must also work together to achieve harmonization in recording remittances. This paper, hopefully, would have contributed to that, even if in a small way.

Bank of Ghana’s inward remittance should be in conformance to treatment remittances in BPM6/BPM7 as total remittances include personal remittances and social benefits. By implication, it includes all household income obtained from working abroad.

Now in the computation of what constitutes total remittances, compensation of employees less expenses related to border, seasonal, and other short-term workers is taken from the primary account. Added to this is a personal transfer which is taken from the secondary account. Capital transfers between households and social benefits are also included in the computation of remittances.

Social benefits include benefits payable under social security funds and pension funds either in cash or in kind. Remittances are mainly derived from two items in the BOP framework: income earned by workers in economies where they are not residents (compensation of employees) and personal transfers from residents of one economy to residents of another (IMF,2008).

These are the standard items in the BOP framework. All other definitions are supplementary items which compiling countries are not required to compile but are encouraged to do. These supplementary items include personal remittances, total remittances, and total remittances and transfers to non-profit institutions serving households Bank of Ghana’s compilation of remittance aggregates can be a very tricky job because no single data item in the balance of payments framework comprehensively captures transactions in remittances.

This paper has taken a critical look at some of the issues in the compilation and analysis of remittances in BPM6/BPM7. Bank of Ghana should critically address those relevant outstanding issues that arise from the compilation and analysis of remittances, difficulty in obtaining migration and other statistics, identification of transaction channels, and lack of coordination between regulator and MTCs and Fintech companies in the tracking and tracing of foreign currencies that have been deposited in their respective nostro- accounts.

Bank of Ghana must adopt proactive measures to ensure that all international remittances are captured and managed effectively as they could contribute to foreign exchange reserves that could support the stability of the Cedi. To carry out effective and efficient public policies to channel remittances into productive projects, the government has to look at what motivates Ghanaians to send money home, particularly beyond individual family remittances, and craft its policies to take advantage of it.

While the policies and initiatives undertaken so far to augment the impact of remittances are primarily aimed at encouraging the sending of remittances through official channels, the utilization aspect of remittances has been largely ignored by the government authorities.

Hence, directing remittances to productive investments is a challenge for the government. Families of migrant workers should be encouraged and trained so that they can undertake small businesses. This will generate jobs and help improve the domestic economy. In the long run, migrant workers can come back and be reintegrated into the country, bringing in better skills and technology.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

First, Bank of Ghana must retrieve all foreign exchange accumulated to the newly Money Transfer Companies and other 11 Fintech Companies in the foreign remittance space to be in compliance with the Foreign Exchange Act 2006 Act 723 (Section 15 deals with Foreign Exchange Business and International Payments. Section 15 Sub-section 4 states the exporter who fails to repatriate proceeds from merchandised exports through an external or correspondent bank commits an offence and is liable on summary conviction to a fine of not more, than five thousand penalty units or to a term of imprisonment of 10 years.

Foreign remittance could be classified as Invisible earnings as Ghanaian workers in abroad through their sweat and toils. The Parliament must revisit the Payment Service and Systems Act 2019 Act 987 so that the sanctity of Foreign Exchange Act 2006 Act 723 is maintained and complied with by all Money Transfer Companies and the 11 Fintech companies licensed by the Bank of Ghana for the period between 2019 to 2024.

Second, the Bank of Ghana must strengthen its procedures and processes of capturing, tracking and tracing of global inward remittance data collection and analysis (including an assessment of the World Bank yearly remittance aggregates) to improve on remittance data and the need for the Bank of Ghana to adopt specific practical guidance on data sources and compilation methods to improve on the existing methodology to address the discrepancies between Bank of Ghana data and World Bank inward remittance data. The adequacy of practical compilation guidance concerns compilers, who, as a result, often produce data that is more credible than other balance of payments components.

Third, the Ministry of Finance and Bank of Ghana must ensure the MTCs and Fintech companies in the international remittances space reimburse the Bank of Ghana’s Nostro Accounts or authorized dealer commercial bank with all foreign exchange components of all foreign exchange accrued as it was previously done in the early 2000s and also in compliance with Foreign Exchange Act 2006 Act 723.

Foreign exchange from international remittances, for instance, could help to reduce the current account deficit and also help to stabilize the local currency against major trading currencies like US$, Euro and UK Pound Sterling. The Bank of Ghana should be prepared to reconcile the Nostro Accounts of all MTC and Fintech companies. Bank of Ghana should commission some of the international audit firms to conduct forensic audits on all MTC and Fintech companies.

In other emerging economies like Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Pakistan, remittances have been a key pillar of foreign currency earnings providing a substantial cushion against the widening trade deficit and thereby enhancing the external sector resilience of the country. Being a major source of foreign exchange earnings, workers’ remittances have covered around 80 per cent of the annual trade deficit, on average, over the past two decades, MTOs and Fintech companies are required to report to central banks.

Moreover, unlike many merchandise export categories, there is no import content involved in this source of foreign exchange earnings. Therefore, strengthening remittance inflows to the country brings several macroeconomic and socioeconomic benefits, mainly narrowing the current account deficit of Balance of Payments (BOP), supporting economic growth, improving forex liquidity in the banking system, alleviation poverty, income disparities and regional disparities, and, reducing the fiscal burden on social security payments.

Fourth, Bank of Ghana must commission external audit firms to conduct forensic audits on the MTOs and Fintech companies’ nostro accounts that are benefitting from foreign currencies as against the Foreign Exchange Act 2006 Act 723. Banks are recognized as the main providers of international remittance services in Ghana in the Foreign Exchange Act 2006 (Act 723).

The Foreign Exchange Act 2006 Act 723 sets out Ghana’s foreign exchange regime, specifying that all inward or outward payments of foreign currency must be made by a bank or authorized dealer. To operate in the market, all remittance providers must partner with a bank and use the daily interbank exchange rates published by the Bank of Ghana. The Act prohibits non-bank entities from sending remittances out of Ghana.

Fifth, the Ministry of Finance, Minister of Foreign Affairs and Regional Integration, and Bank of Ghana, together with their development partners like the World Bank, need to come to a judgment as to whether or not remittances are likely to be a permanent phenomenon in Ghana’s Balance of Payments (BoPs). Drawing on the experience of other countries which have managed significant inflows of remittances (Bangladesh, El Salvador, Jordan) could be an important starting point.

Also, conducting a comprehensive survey to assess the actual scale of remittances and labour migration would help the authorities develop a well-defined strategy to maximize the benefits of remittances while minimizing any negative repercussions. The Nigeria government at the recent World Bank/IMF in Washington US has started a plan to float Diaspora bonds to attract funds held abroad by Nigerian at home abroad.

Nigerian Minister of Finance noted that remittances are certainly one of the ways the nation can increase the supply of foreign exchange and investment in the country. Ghana could adopt the Nigerian Diaspora bonds in the longer term.