Here comes Kofi Akpabli again, with my book in his armpit. After the earlier upper cut, he calls my bluff this time by literally stripping me naked in this post.

Please read this portion of Kofi’s review with a doctor’s prescription; and do not ask why there could be church weddings those days without a wedding cake. Hear the bird Akpabli sing:

Much later, at Sarbah Hall, there is a nickname Tom Sawyer, whose real name counterpart (Nana Amo Adade) was never known.

From the book we learn that names get conferred when an individual distinguishes himself. As an officer of the University of Ghana, Kwesi Yankah was holding several positions at a time, some of which tended to conflict.

In order to curtail that particular occurrence a new regulation had to be drafted into statutes.

The Conflict of Offices is Article 48 of the University of Ghana Statutes (2012). Informally, this became known as the ‘Yankah Amendment.’

The politics of naming has its ideological implications. It is not everybody who has famous siblings. The Yankah brothers of Kojo, Kofi and Kwesi were all given biblical names at birth.

Out of a certain conscious motivation, however, these borrowed names were dropped on the blind side of the Giver.

Our Protagonist confesses to wondering about the opportunity cost of dropping his biblical name. (If you want a clue, it comes with a certain Rock of Ages Blessed Insurance).

Mysticism is another theme I discern in “Pen at Risk.” A mallam is consulted to heal a child afflicted with a protruding tummy. Result? Well, the author still carries the skin marks from Mystic Mallam’s discoloured teeth.

But the carefully preserved details about the life of Kobena Yamoah top it all.

Kobena Yamoah was abducted by dwarfs, who confined him for 7 days and transformed him into a potent spirit.

The narratives backed by photographs is certainly one of the revelations of Kwesi Yankah’s biography.

The man who executed his own resurrection among other feats is easily Ghana’s second Komfo Anokye. No wonder he drew the interest of Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah.

On another level, the subject of mysticism is played out in the author’s own family turf. Indeed, this time our own Protagonist was an acolyte, the active causative agent.

His uncle would invite him over on Saturday mornings, and ask him to help invoke Maamie water, the water spirit, for a ritual dialogue.

“He would fill a glass with scented sea water on which he whispered a prayer. The glass was carefully placed at the center of a chalk design on the floor, that depicted a circle with a lone star at the centre. With the glass of mystical water well positioned, he would chant incantations.”

Young Yankah was asked to focus attention on the water. The Mermaid spirit was believed to manifest only to innocent kids. His duty was to quickly signal when the spirit had materialized. This ritual continued between uncle and nephew for several weeks without anyone knowing. Each time the boy gave the signal, “Wofa’s mood would suddenly change; his tone and comportment drifted. He slipped off his sandals and bowed in courtesy. While on his knees, a dialogue would ensue with the spirit, where he poured out all his wishes and demands to the mermaid.”

This one is not in the book but I cannot help but visualize Young Kwesi Yankah mischievously blurting out, ‘Wofa waaba ooo’! in that rich Agona dialect.

Well, several years after, “Pen at Risk” came out with a special announcement. “I now hereby confess I never saw any Maamie Water spirit throughout the engagements but dared not disappoint Wofa”!

Also to be gleaned from this book is the theme of embracing the consequences of one’s actions and circumstances. Our Protagonist makes art of these. For an incident that gave him suspension from secondary school, Yankah recounts with such bonhomie.

He and his schoolmates had run to Winneba town for an International Ramblers Band dance event. Hear him: “At the dance, we had securely set table at the peripheries of the venue which was an outdoor pavilion, earmarked for state balls … Sited close to the shore, this was a fantastic experience, with the cool Atlantic breeze caressing our bodies as we enjoyed the latest tunes.

“My luck ran out when I spontaneously stood and dashed to the crowded dance floor in response to the hit tune, Ama Bonsu. That was a terrible mistake. As I twisted my body and gyrated my torso on the floor eyes closed, I bumped into a fellow dancer, lifted my eyes and realised I was eyeball to eyeball with a familiar face: the fearsome Senior Housemaster, Mr Kobena Asmah. Shieeeee!”

In another episode, he was in the middle of a school athletic competition and as he cruised towards victory, a wardrobe malfunction happened inside his boxer’s shorts of all places. To control damage on the rather embarrassing incident, he diverts attention from the source of the issue.

“At the blast of the whistle, I swiftly took off and easily assumed a comfortable lead ahead of three other competitors. I widened the gap over a period until the last 50 yards when, under circumstances beyond my control, I was compelled to slow down, holding my tummy. My tummy which I held that day was only a metaphor. The real truth hung elsewhere.” Who does that?

Finally on the theme of acceptance and making the best of situations, is one of my favorite episodes in the entire work. Yankah might underrate it, but his avant-garde approach to his customary wedding about 50 years ago shows more about the man than one would care to think.

Here, one must also credit the bride who accepts a wedding where there was no cake nor refreshment.

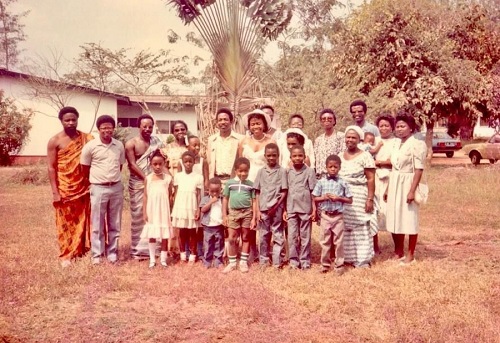

By the way, the pictures of the about 15-member wedding congregation make interesting linkages: younger versions of Kofi Saah, Albert Awedoba, Kojo Yankah his brother, and Kofi Anyidoho the famous literary scholar who functioned as Yankah’s best man.

The triumphs of this poor man’s wedding story occurred in 2015, much later. While the author was serving as Vice Chancellor at Central University it dawned on the couple that they had been in love for the proverbial 40 years.

What kind of wedding reception couldn’t they afford?

At the cozy commemorative ceremony, Dr Mensah Otabil General Overseer, International Central Gospel Church and Chancellor of Central University who officiated, had this to say:

“This glamorous event is a delayed reception for a marriage that took place several years ago. The couple, Kwesi and Victoria that was broke at the time can now afford a great reception several decades after the church wedding. Please enjoy yourselves, and praise the Good Lord!’

There is a small phrase that the author throws in there, a phrase which many readers might miss.

“Victoria and I wept that day.”

Enough said.

[KOFI AKPABLI]

Ei Kofi Akpabli, why do you do me so?

kwyankah@yahoo.com