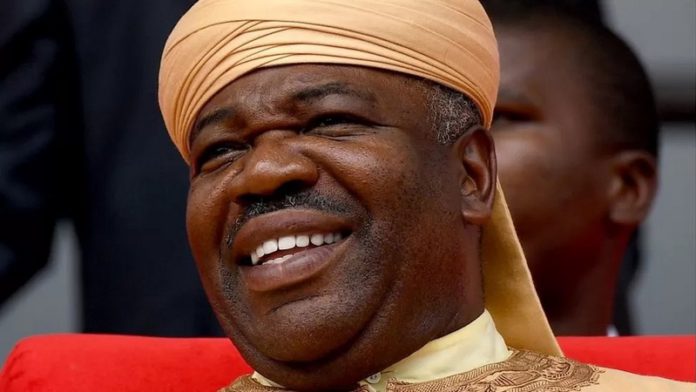

Ali Bongo, the man ousted as Gabon’s president, is a man of many faces.

To some, he is a spoilt, playboy prince who saw ruling the oil-rich Gabon as his birthright; a one-time funk singer who stepped into his father’s shoes to continue his family’s (now 53-year long) rule.

To others, he is a reformer – a man seeking to diversify the economy and boost Gabon’s international status with an ambitious environmental agenda.

But an apparent military coup has pushed tensions to the surface in this country of just more than two million people.

The soldiers said they were annulling the results of Saturday’s polls – Ali Bongo had been declared the winner but the opposition said the election had been rigged.

The military say they have put Mr Bongo under house arrest.

Gabon’s outsider

Ali Bongo was born Alain Bernard Bongo in neighbouring Congo-Brazzaville in February 1959.

Even his birth was controversial – rumours, which he has always denied, have persisted for years that he was adopted from the Nigerian south-east at the time of the Biafran war.

The young Alain Bernard was still in primary school when his father Omar Bongo took control of Gabon in 1967. Already, however, the groundwork was being laid for criticisms which would haunt him later in life.

“He wasn’t born in the presidential palace, but almost. He was about eight when his father became president,” François Gaulme, a French historian and author on Gabonese politics, told the BBC.

“The fact that he went to the best schools in Libreville and didn’t learn local languages was something he would get criticised for later on.”

At the age of nine, Ali Bongo was sent to a private school in the upmarket Paris suburb of Neuilly, and later, to the Sorbonne where he studied law. This international upbringing led many in Gabon to view him as an outsider.

Alain Bernard became Ali and his father Omar in 1973, after converting to Islam – the only members of their family to do so.

The decision was widely seen a way to attract investment from Muslim countries. But the elder Bongo, who was previously an animist and not baptised in the Christian faith, also evoked spiritual reasons for his conversion.

Funk music and freemasonry

It was never all about politics for the young Ali Bongo, however. He showed an early passion for football and music – something inherited from his mother, the Gabonese singer Patience Dabany.

A reputation for being a playboy during his youth was cemented with the release of his 1977 album A Brand New Man, produced by Charles Bobbit, the manager of funk legend James Brown.

“Let me be your darling, Your everything, ’til the end of time,” Bongo crooned on the title track.

Within four years of the album release, he had turned his attention to politics.

Ali Bongo served in his father’s government as minister of defence, a role he held for 10 years. Before that his first appointment, as Gabon’s foreign minister in 1989, ended after three years because of a constitutional change requiring ministers to be over the age of 35. He was 32 at the time.

However, it seems he wasn’t immediately seen as a natural successor to his father.

“In the beginning, the Gabonese people didn’t see [Ali Bongo] as a serious candidate,” said Mr Gaulme.

“But in the end, he has been more thoughtful than he seemed. The first time people saw he could be serious was when he restructured the army.”

Gabon’s voters were still apparently unconvinced by the time of his father’s death in 2009. But Ali Bongo re-emerged as a more reserved figure, attempting to dress down and travelling to campaign in the provinces.

In the end, he was elected, winning 42% of votes.

“I won my place, it didn’t fall in my lap,” he said of his election victory. But throughout his entire time in office, President Bongo’s legitimacy has been questioned by his opponents.

The claims would resurface in 2016, when the main challenger in the presidential election was Jean Ping, the former African Union chairman and father to two of Mr Bongo’s sister’s children.

Mr Ping alleged fraud in one of the president’s main strongholds, Haut-Ogooué province, where Mr Bongo won 95% of the vote on a turnout of 99.9%.

He won overall by the slimmest of margins – just 6,000 votes.

Civil society backed up the allegations of rigging, which were denied by the ruling Gabonese Democratic Party (PDG).

Corruption allegations

Rights groups also allege the Bongo family turned Gabon into a “kleptocratic regime”, looting its natural resources, oil wealth and rainforests, while members of Gabon’s political opposition have long accused family members of embezzling public money and running the country as their private property.

Pictures of Real Madrid fan President Bongo driving Argentinian footballer Lionel Messi around the capital in a flashy car made headlines in 2017.

A seven-year corruption investigation by French police into the Bongo family, which revealed assets including 39 properties in France and nine luxury cars, was dropped in 2017.

There had been insufficient evidence of alleged “ill-gotten gains” to charge any of the family members, reported French news agency AFP.

The family strongly denied all the allegations.

Journalists have also pointed to the close and personal links between Gabon’s elite families as evidence of powerful networks of patronage. African news site Jeune Afrique (in French) has branded them “fiefdoms”.

Mr Bongo has also been criticised over his prominent role in the Freemasons – a society whose Gabonese chapter he led, as lodge master.

He is one of a handful of recent and present Francophone African presidents whose Freemason membership has been out in the open – the others being Congo-Brazzaville’s Denis Sassou Nguesso, Chad’s Idriss Déby, and former President François Bozizé of the Central African Republic, according to French author Vincent Hugeux.

However, his supporters point to his drive to diversify Gabon’s oil-dependent economy, in the face of declining oil reserves.

Analyst Paul Melly of the British think-tank Chatham House told The Guardian that Ali Bongo was “very sharp and he could see that the difficulty with producing raw materials was that it doesn’t create many jobs.

“His goal has been to move Gabon to a higher-tech, skilled economy,” Mr Melly explained.

Despite this strategy, the oil sector accounted for 38.5% of GDP and 70.5% of exports in 2020, the World Bank reported. Critics also say the president has done little to funnel oil wealth to the multitudes that live in poverty.

Ali Bongo has created new investments in mining and a “serious effort to develop a more environmentally sustainable approach to use of the rainforest”, Mr Melly told the BBC.

The president’s strategy has protected Gabon’s share of the Congo basin rainforest and helped the country remain one of the world’s few net absorbers of carbon dioxide.

And in 2021, Gabon became the first African country to receive payment for reducing carbon emissions by protecting its rainforest.

President Bongo has used his own contacts to press harder for a stronger economy, travelling the world to find new investors and partners in countries like Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, while still keeping close ties with France.

It was during a visit to Saudi Arabia for an investment conference in October 2018 that the president suffered a stroke.

He was sidelined for almost a year and in early 2019, following calls for him to step down, mutinying soldiers attempted a coup.

It was not successful, however, and the rebels were arrested by the authorities. After eventually returning to his post, Mr Bongo embarked on an image revamp, putting himself forward as a man of rigour bent on rooting out “traitors” and “profiteers” in his inner circle.

But he struggled to shake off the perception that he was an ailing man, unfit to lead. At King Charles’ coronation in May he was filmed using a walking stick to slowly progress to his seat.

Fast forward a few months and Mr Bongo is said to be under house arrest, with soldiers declaring a coup for the second time in four years.

Shortly afterwards, large crowds flooded onto the streets, waving Gabonese flags and applauding the army. Clearly, many in Gabon seek change and after 53 years, it might be that the Bongo family’s time in power has come to an end.