Last month, Atiq Ahmed, one of India’s most dreaded gangster-politicians, was shot dead live on TV along with his brother. The grisly murder marked the end of his four-decade-long reign of terror in Prayagraj, a city once known for its rich culture. Soutik Biswas in New Delhi and Vikas Pandey in Prayagraj piece together Ahmed’s tumultuous life, in which the boundaries between crime and politics became blurred.

On a foggy January morning in 2005, Raju Pal, a newly-minted lawmaker, was travelling in the northern Indian city of Prayagraj (formerly known as Allahabad) when two vehicles suddenly appeared out of nowhere, swerved dangerously and pulled up in front of his Toyota SUV.

More than half-a-dozen men jumped out and began firing into the car at Pal. After raining several rounds from their handguns, they walked away. Bystanders pulled out the crumpled, bleeding legislator and carried him to another vehicle to take him to the hospital.

Then the men returned to attack their dying target some more.

Ravindra Pandey, a crime reporter, was sipping coffee in a bustling cafeteria when he spotted a convoy of cars carrying the assailants race by, unleashing a barrage of bullets at the vehicle ferrying the wounded politician to the hospital.

They were in hot pursuit until the vehicle reached the hospital. In a final act of ruthless brutality, the men fired a couple of rounds into an inert Pal to make sure he was dead. Doctors found 19 bullets in his body. The lawmaker, who allegedly had close links with the underworld himself, had been married for just nine days.

“We saw the shooting. The entire city saw the shooting. This was the first such incident here. Everyone knew who was responsible for the attack,” recounts Mr Pandey.

At that time, Atiq Ahmed was already Prayagraj’s most feared gangster-turned-politician. A year before the killing, he had become an MP after five consecutive terms as a legislator from the city in Uttar Pradesh state.

Pal was allegedly killed because he had dared to challenge Ahmed on his own turf. Ahmed had bequeathed his Allahabad West seat in the state elections to his brother and fellow strongman, Ashraf, in order to fight – and eventually win – a parliamentary election from neighbouring Phulpur. However, Ashraf had suffered a shock defeat by 4,000 votes at the hands of Pal. The gangster and his men had reportedly taken revenge by getting Pal murdered, and were named as the main accused in the case.

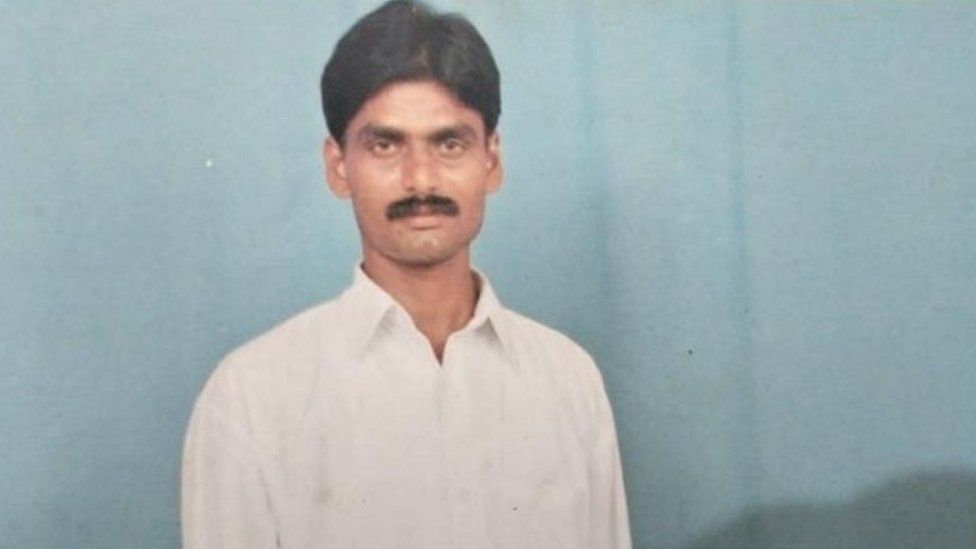

Ahmed, a portly man sporting a handlebar moustache and his trademark white turban, exuded an aura of fear wherever he went, embodying the archetype of a gangster-politician.

For over 40 years, the son of a poor tanga-wallah (horse-drawn carriage driver) and a homemaker mother held sway over the criminal underworld of a quiet city situated at the confluence of the Ganges and Yamuna, two of India’s holiest rivers.

Prayagraj has been famous for its poets, singers, artists, writers and lawyers (India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Bollywood legend Amitabh Bachchan were born here). But its deceptively tranquil exterior concealed a combustible mix of crime and politics.

Nobody contributed to this infamy more than Atiq Ahmed. At home, he was a doting father to five sons, kept pedigreed dogs, threw lavish parties and hosted mushairas (poetry recitals) for his friends, even featuring a respected Bollywood lyricist once.

Outside, he reportedly seized properties and businesses, extorted money from businessmen, issued counterfeit cheques for purchases and got his rivals beaten up in prison. Many police officers and politicians reportedly sided with him and helped him. Even the courts appeared to be cautious: in 2012, 10 high court judges recused themselves from a hearing on whether to grant him bail.

Unsurprisingly Ahmed had a long resume in police records. He was the leader of the so-called “Inter-State Gang 227” and had accumulated nearly 100 cases, including murders and kidnappings. A lot of the time he had remained at large and in plain sight.

The actual number of Ahmed’s crimes are much higher because “people feared him and didn’t report hundreds of cases”, says Lalji Shukla, a former top police officer in Prayagraj.

Yet, it was only in March this year that Ahmed was found guilty in a case of kidnapping and sentenced to life in prison – the first time he was convicted. Mr Shukla attributes this delay to Ahmed knowing “how to manage the system”.

“He would frequently miss court dates and threaten witnesses. Even some witnesses who didn’t fear him would eventually get tired after many years of court dates,” he says.

But a few days after the conviction, on the night of 15 April, it all ended in a rather macabre manner.

Ahmed and his brother were gunned down point-blank on live TV outside a hospital in Prayagraj in the presence of more than a dozen armed policemen. The brothers were speaking with journalists on their way to a routine medical examination.

The police arrested three men who, they said, killed the brothers because they wanted to “make a name for themselves in the criminal world”. The murders shocked the country and the state government swiftly ordered an investigation.

“No mafia can spread terror in Uttar Pradesh anymore,” Yogi Adityanath, chief minister of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-ruled Uttar Pradesh, said days after the murder. He didn’t mention Ahmed directly.

Atiq Ahmed was born in a Muslim-dominated neighbourhood in Prayagraj in 1962.

Not much is known about his early life apart from the fact that he dropped out of high school and got involved in petty crimes.

By 1979, however, Ahmed appeared to have come of age. He was accused in a case of murder, but the charges could not be proved.

Over the next decade, he burnished his credentials as a gangster, police say. He stole scrap metal from railway yards, secured government contracts after threatening rival contractors and usurped land and property belonging to others. He also joined a gang led by a gangster-turned-municipal corporator called Shauq Ilahi, popularly known as Chand Baba.

By 1989, Ahmed was eyeing a career in politics. The mentor and his follower fell out when they both stood against each other in elections to the state assembly that year. (IIahi asked Ahmed to stand down; and the latter refused.)

Following the announcement of election results, or perhaps during the vote counting process (there are conflicting reports), a violent gang war broke out on the streets of the city between the supporters of the now rival gangsters. In the melee, Ilahi, who was the primary target, was killed. With the elimination of his mentor and a resounding victory in his first election as an independent candidate, Ahmed was thrust into the limelight.

Over the next three decades, Ahmed grew into Prayagraj’s most feared gangster. Mr Shukla remembers arresting him thrice, including for murder, but each time Ahmed got bail. “He had connections and supporters everywhere. Everyone feared him,” he says.

Thanks to these connections, Ahmed’s power and influence as a gangster soared. He often spent time in prison as an undertrial for his illegal activities, yet remained undaunted – he frequently summoned his rivals and businessmen to jail to extort money, ordered their beatings, and even circulated videos of their mistreatment as proof of his continued dominance.

In 2018, a businessman named Mohit Jaiswal made a police complaint alleging that he had been abducted from Lucknow and taken to the Deoria prison, where Ahmed was being held. Jaiswal told journalists that he was brutally beaten by the gangster, his henchmen, and even the prison staff.

Police officials in Prayagraj speak about Ahmed forcibly “capturing” a film theatre, a hotel, a workshop and a restaurant in the city. “In the internecine gang wars, he ended up harassing Hindus and Muslims alike. In fact, many of his victims belonged to the Muslim community,” Mr Shukla says.

Rajkumar Ojha, a local resident, tells the story of how Ahmed waded into a land dispute involving his brothers, offered to mediate and ended up forcibly getting the family plot registered in his wife’s name at a throwaway

price. “When I met him later, he taunted me saying that I had not been able to handle my brothers properly and therefore met this fate,” says Mr Ojha.

Zeeshan Ali, one of Ahmed’s relatives, vividly recalls a terrifying incident that occurred in his home two years ago. A group of armed men forcefully entered his house, demanding that he sign over a plot of land in the gangster’s name. Mr Ali received a call from Ahmed himself, ordering him to comply.

According to Mr Ali, Ahmed presented him with two options: either surrender the land’s ownership or pay him a significant sum of money, equivalent to a third of the land’s value, in cash. “I remained silent. Then Ahmed ordered his men to kill me. They began hitting me but I managed to escape,” Mr Ali says.

Ahmed’s influence extended beyond Prayagraj. In one incident, he led an armed gang to try and seize an empty plot of land owned by a businessman in an upscale neighbourhood in the state capital of Lucknow, some 200km away.

“They just arrived in the morning, took out their guns and said they owned the land,” says a senior police official, who wanted to remain unnamed. “We stopped them from claiming the land forcibly”.

Days later, Ahmed and his men reportedly barged into a hotel owned by the businessman, and instructed the manager to switch off the CCTV cameras. He then allegedly listed the names of over a dozen powerful people in the city and said to the manager, “Do whatever you want. Take my photo and give it to these people if you like.”

Sushil Gurnani, the businessman, later told news networks: “They came into our hotel and said: ‘This land was yours until yesterday. From tomorrow it is ours.’”

“They said go and tell the chief minister and police if you want.”

In July 2008, Atiq Ahmed along with five other jailed Indian MPs – who collectively faced more than 100 cases of kidnapping, murder, extortion and more – were furloughed by the government so they could cast their ballots in a no-confidence vote that it was facing over a controversial civilian nuclear deal with the US.

Pictures show a beaming Ahmed in a safari suit entering the parliament. The ruling Congress party-led UPA government narrowly survived the vote, and the six furloughed MPs then returned to jail.

“Judging by the lengthy list of criminal cases in which he stood accused, Ahmed was equally proficient in running a criminal enterprise as he was conducting constituency service,” wrote Milan Vaishnav in his book When Crime Pays: Money and Muscle in Indian Politics.

Mr Vaishnav, a political scientist, provided a vivid vignette of Ahmed’s life as a politician.

“Locals marvelled at this weekly durbar, where Ahmed, one ear pressed to his mobile phone and other taking in requests for constituency service, would mutter orders to his personal assistant or stenographer”.

“The party headquarters in which Ahmed would hold forth often bore close resemblance to an armoury than an administrative office, the walls impressively lined with imported automatic weaponry,” Mr Vaishnav wrote.

Gangsters like Ahmed joined political parties, or formed their own, mainly for protection. They usually won in seats where social divisions driven by caste or religion were sharp and the government was seen to be failing to carry out its functions – delivering services, dispensing justice, or providing security – in an impartial manner.

Like most gangster-politicians Ahmed had led a tangled life. From 1989 to 2002, he won the same seat in Prayagraj for five consecutive terms. He began as an independent candidate and later became a leader of the influential regional Samajwadi Party. Finally, he joined Apna Dal, a rump party formed by a lower-caste leader.

Ahmed had the most success during the rule of the Samajwadi Party and was known to have a close relationship with its leader, Mulayam Singh Yadav, who died last year. It was the Samajwadi Party that gave him a ticket to contest from Phulpur, a prestigious seat that had previously sent Jawaharlal Nehru to parliament three times.

As a leader of the Samajwadi Party, Ahmed did not hesitate to use violent tactics. He was allegedly involved in the infamous 1995 “guest house attack” on Mayawati, the Dalit leader of the regional Bahujan Samaj Party, who was then running a fraying coalition government with the rival Samajwadi Party. Ahmed was allegedly part of a group which stormed into a guest house where Mayawati was holding a meeting – to discuss whether to pull out of the government – and assaulted her.

When Mayawati returned to power in Uttar Pradesh between 2002 and 2003, Ahmed felt vulnerable for the first time. Many of his properties, including a sprawling office where he met his people, were razed to the ground and he was jailed. But his fortunes changed again when the Samajwadi Party (SP) won elections in 2003.

He was now a seasoned politician.

In public meetings, Ahmed worked the crowds and spoke like an astute politician. He spoke about equality, secularism, social justice and education of girls. “Education is the biggest love you can give to your children,” he told a cheering crowd many years ago.

When reporters quizzed him on his criminal record, Ahmed would remind them that a court had quashed a record 123 cases against him in a single day. “Has it happened anywhere else in the world – the fact that I face so many fake cases?” he asked a reporter.

He often took on the the Hindu nationalist BJP. He once said people filed cases against him because he was fighting for Hindu-Muslim amity. He claimed he was interested in capturing power to “improve the lives of people”.

Ahmed presented himself as a sacrificial figure in politics, claiming he had little personal life because he was working for the people. “He gave money to the poor to settle their medical bills, send their children to school. He helped Hindus and Muslims alike. But there was nothing charitable about it. It was all about cultivating an image like other gangster-politicians do,” says Anupam Mishra, editor of The Leader, a prominent Prayagraj newspaper.

A politically successful man like him would always attract enemies and go to prison, Ahmed said once. He compared himself with Nelson Mandela, saying that even the revered statesman “was in jail for 27 years”.

“Mandela was once a most wanted man. Then he became his country’s most respected ruler.”

He consolidated his political power between 2003 and 2007. But just before the Samajwadi Party’s rule ended and fresh elections were called in 2007, a horrific case further triggered his downfall and seemed to make him fall out of favour with the Muslims in his constituency – two young girls were abducted from a madrassa and gangraped.

This had caused immense outrage within the community, and many people pointed fingers at Ahmed and his men, although the gangster’s name was not mentioned in the police complaint. “Ever since this incident, Ahmed lost the goodwill of his community who were his biggest voting bloc,” says Mr Ali.

Two years later, Ahmed lost his seat in parliament. He never won an election after that.

But he continued to contest polls, was in and out of jail and still held sway in the world of crime.

In 2017, Mr Adityanath’s BJP government came to power. Since then, Ahmed spent most of his time in jail.

On a balmy February evening this year, Umesh Pal was shot dead outside his home by gunmen suspected to be part of Ahmed’s gang.

CCTV footage showed Umesh, a lawyer and key witness in the 2005 killing of Raju Pal, talking on his phone and stepping out of a white Hyundai SUV near his home.

Even as his armed security guard steps out of the front seat, a young man brandishing a revolver shoots at Pal. The 48-year-old lawyer staggers into a lane, and a few other men emerge, shooting at him. A bomb detonates, shrouding the busy street in an envelope of smoke, and people run helter-skelter.

Ahmed’s family – his wife, son and brother – were charged with murdering Umesh. Since Ahmed and his brother were already in jail in connection with other cases, the implication was that they had ordered the daylight hit. (The trial of Raju Pal’s murder was still grinding on in the courts).

Ahmed had been spending time in a prison in Gujarat state since 2019 after India’s top court ordered that he should not be kept in Uttar Pradesh to stop him from running his gang from inside the jail.

By then, he appeared to have fallen out of favour with his political patrons. Days before his murder, his son Asad, a law student, was killed by the police. Asad was allegedly seen in CCTV footage shooting at Umesh Pal and he was named as an accused in the murder.

Police declared that they seized and demolished the gangster’s properties – houses, offices, businesses – worth nearly 10,000 million rupees.

The cycle of violence and retribution that Ahmed unleashed had continued long after he went to prison. A key witness had been eliminated in broad daylight in February. Three months later, Ahmed himself met a grisly fate.

Did someone order his killing? Nobody quite knows. An epilogue – or two – on Prayagraj’s seething underworld is possibly still waiting to be written.