When his son was sent to fight in Ukraine, Sergei begged him not to go.

“You’ve got relatives there. Just refuse,” Sergei recalls telling Stas, who was already an army officer. “But he said he was going. He believed it was right. I told him that he was a zombie. And that, unfortunately, life would prove that.”

Sergei and Stas are not the real names of this father and son. We’ve changed them to protect their identities. Sergei has invited us to his home to tell us their story.

“So off he went to Ukraine. Then I started getting messages from him asking what would happen if he refused to fight.”

Stas told his father about one particular battle.

“He said the [Russian] soldiers had been given no cover; there was no intelligence gathering; no preparation. They’d been ordered to advance, but no one knew what lay ahead.

“But refusing to fight was a difficult decision for him to take. I told him: ‘Better to take it. This is not our war. It’s not a war of liberation.’ He said he would put his refusal in writing. He and several others who’d decided to refuse had their guns taken off them and were put under armed guard.”

Sergei made several trips to the front line to try to secure his son’s release. He bombarded military officials, prosecutors and investigators with appeals for help.

Eventually his efforts paid off. Stas was sent back to Russia. He revealed to his father what had happened to him in detention: how a “different group” of Russian soldiers had tried to force him to fight.

“They beat him and then they took him outside as if they were going to shoot him. They made him lie on the ground and told him to count to ten. He refused. So, they beat him over the head several ties with a pistol. He told me his face was covered in blood.

“Then they took him into a room and told him: ‘You’re coming with us, otherwise we’ll kill you.’ But then someone said they’d take my son to work in the storeroom.”

Stas was a serving officer when Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February. President Vladimir Putin promised that only professional soldiers would take part in his “special military operation.”

But by September that had all changed. The president announced what he called a “partial mobilisation”, drafting hundreds of thousands of Russian citizens into the armed forces.

Many of the newly mobilised troops were quick to complain that they were being sent to a war zone without sufficient equipment or adequate training. From Ukraine there have been multiple reports of mobilised Russian troops being detained – in some cases, locked in cellars and basements – for refusing to return to the frontline.

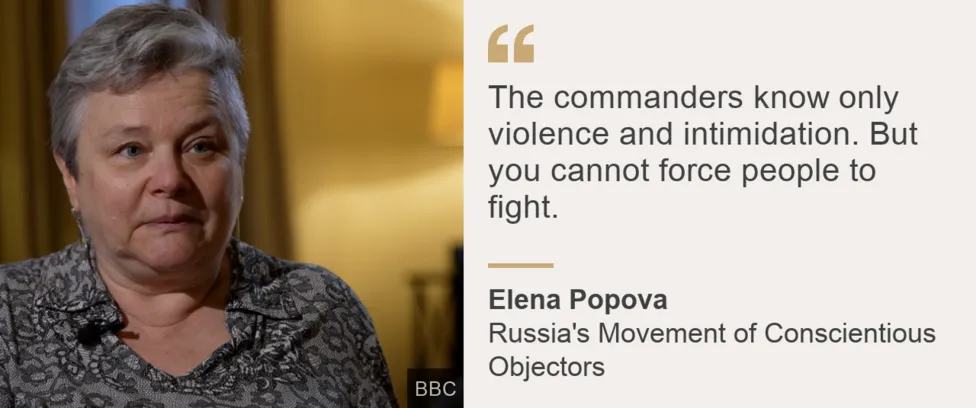

“It’s a way of making people go back into that bloodbath,” says Elena Popova from Russia’s Movement of Conscientious Objectors. “The commanders’ aim is to keep the soldiers down there. The commanders know only violence and intimidation. But you cannot force people to fight.”

For some Russians, refusing to return to the front line may be a moral stand. But there’s a more common explanation.

“Those refusing to fight are doing so because they’ve had more than their fair share of front line action,” explains Elena Popova. “Another reason is the foul way they’re being treated. They’ve spent time in the trenches, getting cold and hungry, but when they come back they just get shouted and sworn at by their commanders.”

The Russian authorities dismiss reports of disillusioned soldiers and detention centres as fake news.

“We do not have any camps or incarceration facilities, or the like [for Russian soldiers],” President Putin insisted earlier this month. “This is all nonsense and fake claims and there is nothing to back them up with.”

“We do not have any problems with soldiers leaving combat positions,” the Kremlin leader continued. “In a situation when there is shelling or bombs falling, all normal people cannot help but react to it, even on the physiological level. But after a certain adaptation period, our men fight brilliantly.”

Andrei, a Russian lieutenant, stopped fighting. Deployed to Ukraine in July, Andrei was placed in detention for refusing to carry out orders. He managed to contact his mother, Oxana, back in Russia to tell her what was going on. Once again, we have changed their names.

“He told me he had refused to lead his men to a certain death,” Oxana tells me. “As an officer he understood that if they went ahead, they wouldn’t get out alive. For that they sent my son to a detention centre. Then I got a text message saying he and four other officers had been put in a basement. They haven’t been seen for five months.

“Later I was told that the building they were in had been shelled and that all five men were missing. They said no remains had been found. Their official status is missing in action. It doesn’t make sense. It’s absurd. The way my son was treated wasn’t only illegal, it was inhuman.”

Back in his living room, Sergei tells me that what happened to Stas in Ukraine has brought them closer together.

“We’re on the same wavelength now,” Sergei tells me. “The wall of misunderstanding between us has gone. All his bravado has gone. My son told me, ‘I never thought my own country would treat me this way.’ He’s changed completely. He gets it now.”

“People here don’t understand how much danger we’re in. Not from the opposing side. But from our own side.”