Many footballers are unsure of their calling once they hang up their boots and Otto Addo was no different.

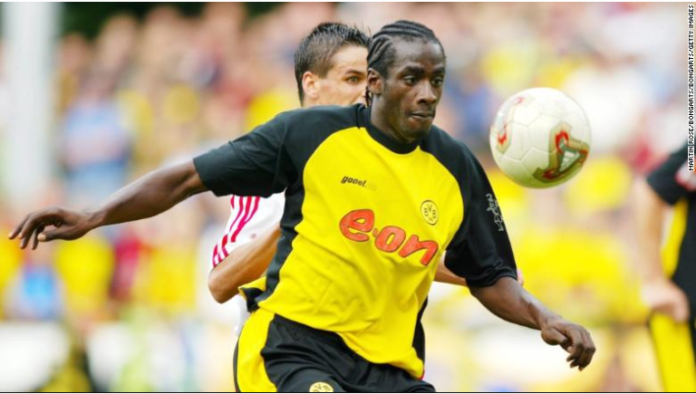

The German-born Ghanaian international had enjoyed a stellar career in Germany, the highlight coming in the 2001-02 season when he won the Bundesliga title with Borussia Dortmund.

Addo, who represented Ghana at the 2006 World Cup, eventually finished his career at his hometown club of Hamburg and it was there that he began to get a sense of what life after playing might be.

After signing in 2007, Addo alternated between playing for the first team and second team, where he began to coach and mentor the club’s young talents.

It was a role he was enjoying until his troublesome knee — which he sustained three serious injuries to throughout his career — eventually forced him to retire.

“I started thinking: ‘Okay, what can I do now?’” Addo tells CNN from Borussia Dortmund’s training centre, where he is now the assistant coach of the first team.

“So I jumped into scouting for about two or three months to see if I would like it because I was sure that I wanted to do something with football — about this I was very, very sure — but I didn’t know which section to go.

“The scouting was okay,” he recalls somewhat unenthusiastically. “You know, traveling alone and watching games alone was quite different and I’m a guy who likes to be around people.

“Then the opportunity came to join the under-19s [at Hamburg] and they asked me if I could join as an assistant and if I could help.

“I stepped in and I liked it. I like to work with young players and with people. It was a good experience and I said: ‘OK … I want to do this for the rest of my life.”

Otto Addo won the Bundesliga with Borussia Dortmund in 2002.

Addo soon became head coach of Hamburg’s under-19s but was lured to Denmark by FC Nordsjaelland to become a coach for an exciting new project.

The club is owned by Ghana’s Right to Dream Academy and provides arguably one of the best routes into European football for some of Africa’s biggest talents.

With his understanding of both German and Ghanaian culture, Addo says he was largely tasked with helping the youngsters get acclimatized to their new home.

“It was perfect for me,” he says.

- ‘Just a number’

Football can be a tough profession and this can be doubly true for young players, in particular those coming from abroad.

Throughout his career, Addo had sometimes noticed that these youngsters could be treated like “just a number” when making the step up from the youth sides to the first team.

“Every time a young player went up, he was kind of left and felt alone,” Addo recalls. “They came to the first team and they were just a number, like number 23 or 24. No one was talking to them. It was a whole different experience.”

It was during his time at FC Nordsjaelland that Addo began to understand how he could best help the next generation of footballers, and he began to carve out a new role for himself.

On top of the coaching and on-pitch analysis he provided, Addo also became a mentor for the club’s youth players and provided support in their personal lives.

Otto Addo vies for the ball with the Czech Republic’s Pavel Nedved at the 2006 World Cup.

“I was starting to write things down,” he says. “Like: ‘How could I create a role of guidance, of helping, of coaching young players?’ I said it would be good if there was somebody who could join the first squad just to [let the kids] know what the coach wants and also to take a little bit more time for the young players for them to adapt to his philosophy.”

It’s a role — one that is “difficult to explain in a few sentences,” he laughs — Addo has since refined, first taking his skills from FC Nordsjaelland to Borussia Monchengladbach before arriving at Borussia Dortmund in 2019, where he remains today.

He explains there are three main pillars — individual video analysis, in which he provides detailed feedback of each training session; transformation on the pitch, which helps players make the jump from youth team to first team; and lastly, but perhaps most importantly, guidance off the field.

“At least once or twice a month, I try to meet my young talent group,” he says. “The young players from the first team and then the best three or four players from the under-23s, under-19s and under-17s.

“Sometimes, we meet together and we eat something. We just talk about personal stuff, you know, if I have a feeling that any player has a problem, I try to meet him privately. I’m always there for them if they want to talk — and some need it more, some less.

“We talk about everything: their private life, because I’m really sure that the better the relationships, the better I can coach them and then they won’t take criticism from me as badly. They should take it as help. I am really keen on building a good relationship between me and the young players.”

Otto Addo during his time at Hamburg in 2013.

At Dortmund, two of Addo’s current students are among the most highly-regarded youngsters in Europe: Erling Haaland and Youssoufa Moukoko.

While 16-year-old Moukoko is considerably further back in his development — only recently making the step up into the first team — Haaland has now been taking European football by storm for a number of years.

After making his Champions League debut in 2019, it took the Norwegian striker just seven games to score 10 goals — the fastest any player has reached double figures in the competition’s history. He’s also the first teenager to score 10 goals in a single Champions League season.

At just 20 years of age, Haaland is unquestionably one of the best strikers in the world.

“What what makes him so special is how he thinks,” Addo explains. “He has got a certain athleticism that he brings with him; he has the body of a sprinter, but I think the main thing is how he thinks. His mind.

“He’s always willing to do more than anyone else on the pitch, but also after training in the gym. He has a very, very good mindset of work, he has a good work ethic, he always wants to score. He’s never satisfied; if he scores three goals, he wants four. If he scores four, he wants five. So this is a very good mentality to build something up.”

- ‘It will change’

It’s not only the next generation of footballers that Addo is guiding but also the next generation of coaches.

Addo is one of the most high-profile Black coaches in a sport that continues to suffer with a lack of representation at the highest level.

While change might be slow, Addo sees a lot of potential in the current crop of players to one day make the transition from the pitch into the dugout.

“In Germany, I think it’s a little bit different because we don’t have so many Black former players who have the [UEFA] pro license,” he explains.

“I think it will change in Germany … it’s the next generations, you know, [David] Alaba kind of players or [Jerome] Boateng, when they stop,” added Addo, referring to Bayern Munich’s star players.

“There are a lot of Black players now playing, and so I think maybe in 10 years, five years when they stop then we will see how it is here. There are a lot of young players who are calling me, who are trying to get in contact with me and I’m trying to help them and to give them advice.

Otto Addo speaks with Borussia Dortmund’s former coach Jurgen Klopp.

“I can see already that a lot of coaches, young coaches actually, no matter what colour, are calling and also asking for help or for guidance. I think it will change in Germany, especially in the next five, 10 years — I’m sure about that.”

While Addo may have been the first to officially create a role like this, he has certainly not been the last; Dortmund says that several clubs have since followed suit and set up the same position.

The 45-year-old’s unique outlook on player development has already taken him to one of Europe’s leading clubs, though Addo remains unsure whether one day he would like to make the step up into a head coaching role.

“I can’t really tell,” he says. “Now, as an assistant coach, it’s fun for me — to work with young players is really, really good. I think it’s an important role. In football, you actually can’t think too far [ahead]. You have to look from season to season … and I’m not really sure if I could do it really, to be honest,” he says with modesty.

“I’m learning day-by-day, and at the moment, I’m happy with the role as an assistant coach, but also with the role of guiding the young players, talented players and helping them to grow up, to step into the adult football scene and to guide them, especially in difficult situations.”