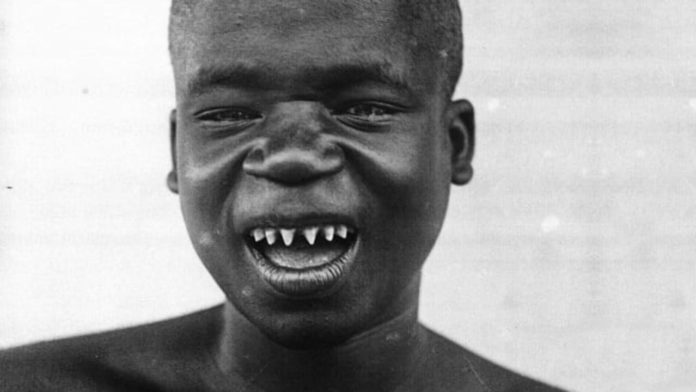

Ota Benga was kidnapped from what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1904 and taken to the US to be exhibited. Journalist Pamela Newkirk, who has written extensively about the subject, looks at the attempts over the decades to cover up what happened to him.

More than a century after it drew international headlines for exhibiting a young African man in the monkey house, the Bronx Zoo in New York has finally expressed regret.

The Wildlife Conservation Society’s apology for its 1906 exhibition of Ota Benga, a native of Congo, comes in the wake of global protests prompted by the videotaped police killing of George Floyd that again shone a bright light on racism in the United States.

During a national moment of reckoning, Cristian Samper, the Wildlife Conservation Society’s president and CEO, said it was important “to reflect on WCS’s own history, and the persistence of racism in our institution”.

He vowed that the society, which runs the Bronx Zoo, would commit itself to full transparency about the episode which inspired breathless headlines across Europe and the United States from 9 September 1906 – a day after Ota Benga was first exhibited – until he was released from the zoo on 28 September 1906.

But the belated apology follows years of stonewalling.

He was a zoo employee

Instead of capitalising on the episode as a teachable moment, the Wildlife Conservation Society engaged in a century-long cover-up during which it actively perpetuated or failed to correct misleading stories about what had actually occurred.

As early as 1906 a letter in the zoo archives reveals that officials, in the wake of growing criticism, discussed concocting a story that Ota Benga had actually been a zoo employee. Remarkably, for decades, the ruse worked.

Who was Ota Benga?

- Captured in March 1904 by US trader Samuel Verner from what was then Belgian Congo. His age is not known, he may have been 12 or 13

- Taken by ship to New Orleans to be shown later that year at World’s Fair in St Louis with eight other young males

- The fair continued into the winter months where the group was kept without adequate clothing or shelter

- In September 1906 he was exhibited for 20 days in New York’s Bronx Zoo, attracting huge crowds

- Outrage from Christian ministers ended his incarceration and he was moved to New York’s Howard Coloured Orphan Asylum run by African American Reverend James H Gordon

- In January 1910 he went to live at the Lynchburg Theological Seminary and College for black students in Virginia

- There he taught neighbourhood boys how to hunt and fish and told stories of his adventures back home

- He later reportedly became depressed with his longing for home and in March 1916 shot himself with a gun he had hidden. He was thought to be aged around 25.

In 1916, following Ota Benga’s death, a New York Times article dismissed as urban legend tales of his exhibition.

“It was this employment that gave rise to the unfounded report that he was being held in the park as one of the exhibits in the monkey cage,” the article said.

The account, of course, contradicted the numerous articles that a decade earlier had appeared in newspapers across the country and in Europe.

The New York Times alone had published a dozen articles on the affair, the first under the 9 September 1906 headline: “Bushman Shares A Cage With Bronx Park Apes”.

Then, in 1974, William Bridges, the zoo’s curator emeritus claimed that what actually occurred could not be known.

In his book The Gathering of Animals, he rhetorically asked: “Was Ota Benga ‘exhibited’ – like some strange, rare animal?” a question that he, as the man who presided over the zoo archives, would know best how to answer.

“That he was locked behind bars in a bare cage to be stared at during certain hours seems unlikely,” he continued, patently ignoring mountains of evidence in the zoological society archives that reveal just that.

An article about the exhibition, written by the zoo director, had in fact appeared in the zoological society’s own publication.

Nonetheless, Bridges wrote: “At this distance in time that is about all that can be said for sure, except that it was all done with the best of intentions, for Ota Benga was interesting to the New York public.”

‘Friendship between captor and captive’

Compounding these deceptive narratives was a book published in 1992 and co-authored by the grandson of Samuel Verner, the man who went to Congo heavily armed to capture Ota Benga and others to exhibit at the 1904 St Louis World’s Fair.

The book was absurdly characterised as the story of friendship between Verner and Ota Benga.

In at least one newspaper account since the book’s publication, the younger Verner also claimed that Ota Benga – who had vigorously resisted his captivity – had enjoyed performing for New Yorkers.

So for more than a century, the very institution and men who had so ruthlessly exploited Ota Benga, and their descendants, contaminated the historical record with untrue narratives that circulated around the world.

Even now, Mr Samper has apologised for exhibiting Ota Benga for “several days”, and not for the three weeks he was held captive in the monkey house.

The zoo has now posted online digitised documents it holds of the episode, among them letters that detail the daily activities of Ota Benga and the men who caged him.

Many of those letters are already cited in my book, Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga, published in 2015.

In the five years since its publication, zoo officials had inexplicably refused to express regret or even respond to media inquiries.

And while I had the opportunity to visit the primate house where Ota Benga was exhibited and housed, the building has since been shuttered to the public.

Best room in the monkey house

Now, Mr Samper says: “We deeply regret that many people and generations have been hurt by these actions or by our failure previously to publicly condemn and denounce them.”

He also denounced founding members Madison Grant and Henry Fairfield Osborn, both ardent eugenicists who played a direct role in Ota Benga’s exhibition.

Grant went on to write The Passing of a Great Race, a book steeped in racist pseudo-science that was praised by Osborn and hailed by Adolf Hitler.

Osborn went on to lead for 25 years the American Museum of Natural History where in 1921 he hosted the second International Eugenics Congress.

Curiously, Mr Samper did not mention William Hornaday, the zoo’s founding director who was also the nation’s foremost zoologist and founding director of the National Zoo in Washington, DC.

Hornaday had littered the cage housing Ota Benga with bones to suggest cannibalism and had brazenly boasted that Ota Benga had “the best room in the monkey house”.

Some feel the conservation society now needs to follow its incomplete apology with rigorous truth-telling befitting a leading educational institution.

The episode offers the zoological society the opportunity to educate the public about the history of the conservation movement and its ties to eugenics.

The Bronx Zoo’s founding principles were among the most influential disseminators of specious racial inferiority theories that resonate still.

One suggestion has been that the society might also consider naming its education centre for Ota Benga, whose tragic life and legacy is inextricably bound to the Bronx Zoo’s.