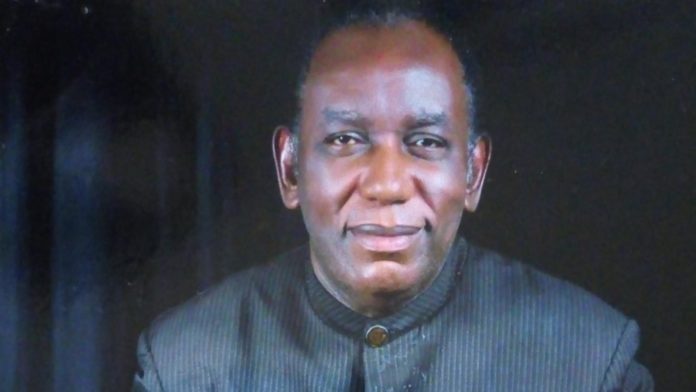

In our series of Letters from Africa, journalist Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani speaks to one of the first African students at the United Kingdom’s (UK) prestige Eton college about his experience of racism in the 1960s and 70s, and about his views on the current debate about apologising for slavery and colonial-era statues.

Three years after obtaining his school-leaving certificate from Eton College in the UK in 1969, Dillibe Onyeama received an official letter informing him that he was banned from visiting the prestigious school.

He had written a book which caused a furore in the UK and offence to the school that has educated generations of British royalty and statesmen.

Published in 1972 when he was 21, the book detailed Onyeama’s experiences of racism during his four years at the boarding school for boys.

“As far as the school saw it, I was indicting them as a racist institution,” Onyeama told me.

“People come to Africa and write all sorts of indicting and shaming experiences and publish it in books and nobody says anything,” he added.

Onyeama was taunted on a daily basis at Eton by fellow students: “Why are you black?” “How many maggots are there in your hair?” “Does your mother wear a bone in her nose?”

He usually responded with his fist and once broke his hand punching another boy’s jaw.

“I gained a reputation for violence,” he said.

When Onyeama performed poorly in academics or excelled in sports, the students attributed it to his race.

When he obtained seven O-level passes, the entire school was confounded.

“‘Tell me Onyeama, how did you do it?’ I am asked time and time again,” he wrote in the book. “‘You cheated, didn’t you?'”

Contacted by the BBC for comment, Eton headmaster Simon Henderson said: “I am appalled by the racism Mr Onyeama experienced at Eton. Racism has no place in civilised society, then or now.”

He added that he would be “inviting Mr Onyeama to meet so as to apologise to him in person, on behalf of the school, and to make clear that he will always be welcome at Eton.”

A long journey to Eton

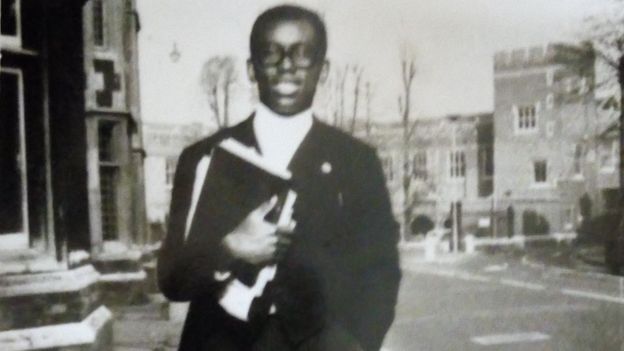

Onyeama was registered to attend Eton on the day he was born in January 1951.

His father, Charles Dadi Umeha Onyeama, studied at Oxford University, worked as a magistrate in British-ruled Nigeria and mixed well with the top of British society, eventually becoming a judge at the International Court of Justice at The Hague.

With the man’s connections, his second son was at birth the first black boy to be registered in the elite school.

But when the time came, Onyeama failed the entrance exams. Another Nigerian boy, Tokunbo Akintola, thus became the first black student in Eton, attracting global media attention.

Onyeama eventually enrolled two terms after Akintola.

But the 14-year-olds, who came from different ethnic groups, did not get along.

“The very person who should have been my best friend, given my predicament, turns out to be more of an enemy,” Onyeama wrote.

Akintola left Eton after about two years and so Onyeama became the first black person to complete his education at the prestigious school.

Onyeama began writing about his experiences at Eton while he was still a student.

“I watched a movie in those days called Tom Brown’s School Days, where the hero was ragged very badly and roasted over a fire,” he said.

“That was the motivation to sort of put pen to paper and start recording some of my own experiences when I was about 17 years old.”

Onyeama’s book is still in print in Nigeria. He would retain the original title, Nigger at Eton, if it were republished in the UK, he insists.

“It is symbolic. I am a black author. I am using it,” he said.

“This was a word flung at me.”

Eton ‘means nothing’ in Nigeria

After Eton, Onyeama got a diploma from the Premier School of Journalism. He returned to Nigeria In 1981 to set up his own publishing company, Delta Publications.

“In England, I got jobs because of Eton,” he said. “It was a passport to any employment at all. But not here in Nigeria. It means nothing at all. Whatever benefits you accrued, like English refinement and etiquette and decorum, it isn’t very important here.”Dillibe OnyeamaMy grandfather had no rudiments of any form of education at all and he knew nothing beyond the ‘kill or be killed’ way of life in those days”Dillibe Onyeama

Grandson of Nigerian slave trader

Onyeama last visited the UK in the 1990s and felt that the racial situation had got “much, much better” since his schooling days in Eton.

“They’ve applied good sense. They’ve said: ‘Look, if you want to have peace, for God’s sake, make a more conducive atmosphere for all races and offer them a sense of belonging’, and to a large extent that has been happening in Britain,” he added.

What about slavery and statues?

He has written 28 books, including The Story of an African God, a biography of his late grandfather, Onyeama the Okuru Oha of Agbaja, a powerful and influential slave trader who became an ally of the British colonialists.

“The slave trade was terrible but it is a historical reality,” Onyeama said.

He sees no need for his family to apologise for the actions of his grandfather, who became an “apprentice” slave trader after his mother died when he was still a child.

“My grandfather had no rudiments of any form of education at all and he knew nothing beyond the ‘kill or be killed’ way of life in those days,” Onyeama said.

“It wasn’t done as a means of oppression. It was a means of livelihood and a demonstration of power and might. It was the way of life in the old Africa before the white man brought civilisation, so to speak,” he added.

He describes as both unfortunate and good the call by protesters in the UK to pull down monuments of those who are regarded as racists or white supremacists.

“It is unfortunate because those monuments represent history – reminding people, educating people,” he said.

But he believes that the British should have known better about the slave trade, while Africans who collaborated with them were merely ignorant.

“You can’t compare people who were not learned and people who were educated,” he said.

“The British claimed to have been the most exposed in the world so they have no excuse for ignorance. They can’t eulogise people who did terrible things to others just because they happened to be black,” he added.

Onyeama’s ban from Eton was finally lifted about 10 years ago, after he received an invitation to a reunion. He was too busy to attend.

He is in touch with some of his former schoolmates on Facebook but they do not talk about the racial abuse he experienced.

“That’s all in the past,” Onyeama said.