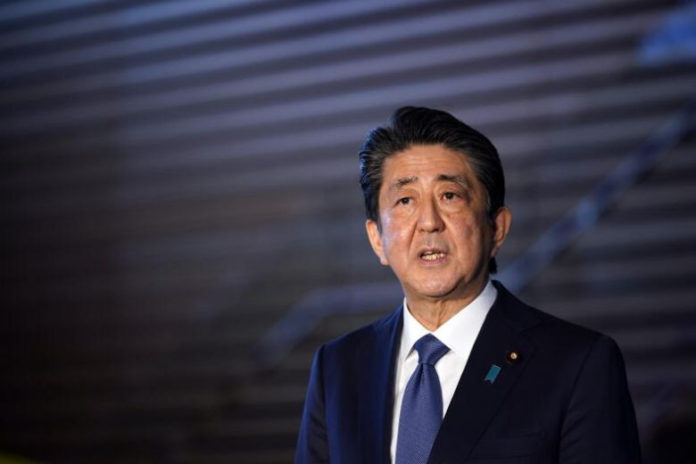

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has declared a one-month state of emergency in response to the rapidly increasing number of coronavirus infections in big cities, though people cannot legally be forced to stay home or businesses be forced to close.

ALSO READ:

- Coronavirus: Akufo-Addo woos doctors

- Photo: Check out Ronaldinho’s new look in prison

- Coronavirus: Moroccans without masks in public risk jail terms

Tuesday’s declaration covers Tokyo and three surrounding prefectures, as well as Osaka, Hyogo, and Fukuoka.

It will be accompanied by a 108 trillion yen ($990bn) stimulus package, representing about 20 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP), though some are worried whether the financial aid will arrive quickly enough.

“We must do everything to protect medical facilities from being overwhelmed, they are now close to capacity,” said Abe during an address to the nation.

“If we can reduce person-to-person contact by 70 or 80 percent, infections will reach their peak in two weeks,” said Abe, who called for a cut of 70 percent in people commuting to work.

The type of lockdown seen in other countries is not possible because the government’s powers to control the population are restricted by the constitution, which was effectively imposed on Japan by the United States after World War II.

Freedom of association and assembly are guaranteed, as is the free choice of residence, “to the extent that it does not interfere with the public welfare”.

The term “public welfare” does not have a clear definition in the document, pointed out Osamu Nishi, a professor emeritus of constitutional law at Tokyo’s Komazawa University, though he sees the current situation as meeting the criteria.

“This state of emergency is perfectly constitutional in the circumstances,” said Nishi, a leading scholar on the constitution. “But only requests and instructions can be issued to citizens, not orders; they can’t be forced to comply.”

The governor of Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost main island, took decisive early action after it became the site of the nation’s first major cluster and declared a state of emergency on February 28.

Despite having no legal basis, citizens took heed and the island was able to lift the measures on March 19.

Hokkaido has reported no new cases in the last two days. The majority of those infected have now recovered, and the island has recorded just nine deaths out of a population of 5.3 million.

In contrast to most of Japan, the island prefecture conducted a lot of tests.

“I never heard about anyone in Hokkaido not being able to get tested,” said Yoko Tsukamoto, a professor of infectious disease at the Health Sciences University of Hokkaido. “Running tests is key.”

Tsukamoto expressed concern the central government waited too long to declare a state of emergency and may pay the price for it.

She said the medical system in the capital is in danger of being overwhelmed if “the number of new cases is in three digits every day”, figures Tokyo has been registering since the weekend.

“The governor of Tokyo has said there are about 1,000 beds for coronavirus patients, but there are about that number of cases already. They need to move the asymptomatic and mild cases out of hospitals to make room,” said Tsukamoto, who is also worried about the number of medical personnel who have become infected.

Forty-four staff at Tokyo’s Eiju General Hospital are infected, while 18 junior doctors at the prestigious Keio University Hospital have been hospitalised with coronavirus symptoms after 40 of them dined together, despite repeated warnings to avoid such gatherings.

The state of emergency declaration will bring large sections of the economy to a virtual standstill and some small and medium-sized businesses are concerned the 2 million yen ($1,836) government grants may not come quickly enough to save them.

Tokyo is home to about 160,000 eateries, plus tens of thousands more in the surrounding prefectures. Many of these are small, owner-operated bars and restaurants that survive month-to-month and will be hardest hit by an extended loss of business.

One such establishment is the Spanish restaurant Los Bacos in a suburb of Kawasaki, just south of Tokyo.

“I’m thinking that I’ll carry on for a few days and see what happens, whether customers come or not. I’ll also talk to the owners of the other bars and restaurants around here,” said owner-chef Nobuaki Motodate, who lived in Spain to learn his craft before opening Los Bacos.

“The country is in a tough situation and I want to do the right thing, but I need to live. I can’t close down for a month. I’d have to go to the bank and ask for money. I think most small eateries are in the same situation,” said Motodate.

“The government is supposed to provide support, but there’ll be a lot of paperwork and it will take time. That’s how things work in Japan,” he added. “For now, I’ve just got to try and put on a brave face.”