In Singapore, one of the first places hit by coronavirus, detectives are tracking down potential positive cases to try to stay one step ahead of the virus. How did they do this and is it too late for the rest of the world?

In mid-January, a group of 20 tourists from the Chinese city of Guangxi arrived in Singapore for Chinese New Year. They visited some of its most glamorous sights.

Also on their itinerary was a non-descript traditional Chinese medicine shop, selling crocodile oil and herbal products. The shop is popular with mainland tourists.

They were served by a dedicated saleswoman who showed them various products, even massaging medicated oil on their arms. The Chinese group finished the tour and went home.

But they had left something behind.

Medicine shop

At that point, the 18 coronavirus cases in Singapore had only been found in arrivals from mainland China.

But on 4 February, Singapore’s government reported that the virus had spread into the local community – and the Yong Thai Hang Chinese medicine shop was its first cluster, with a local tour guide and that enthusiastic saleswoman falling ill.

From that one shopping trip, nine people became infected, including the saleswoman’s husband, her six-month-old baby and their Indonesian domestic helper. Two other staff members also caught it.

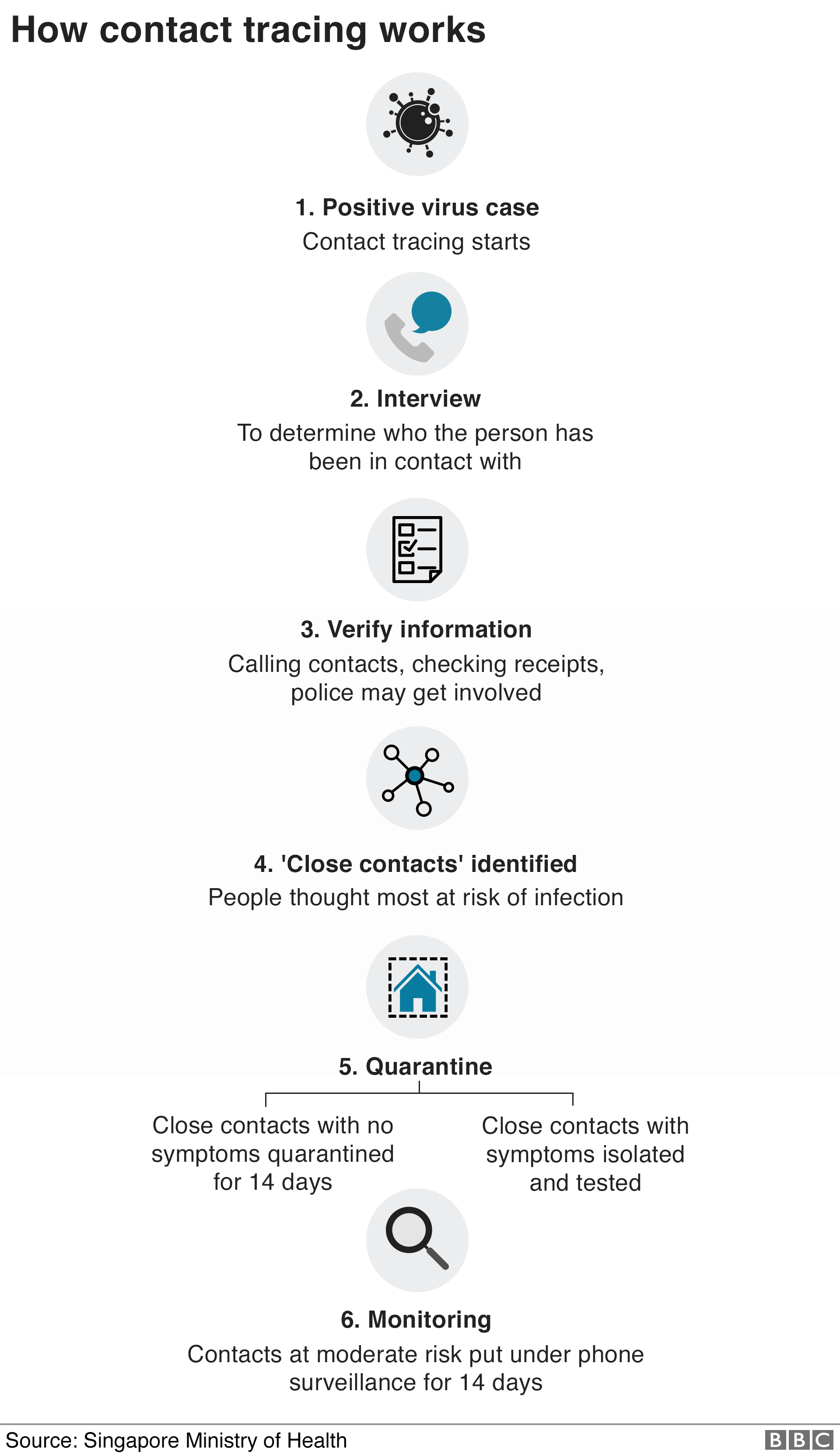

They have now recovered, but it could have been much worse if Singapore didn’t have a sophisticated and extensive contact tracing programme, which follows the chain of the virus from one person to the next, identifying and isolating those people – and all their close contacts – before they can spread the virus further.

“We would have ended up like Wuhan,” says Leong Hoe Nam, an infectious diseases specialist at the Mount Elizabeth Novena hospital and a Singapore government advisor.

“The hospitals would be overwhelmed.”

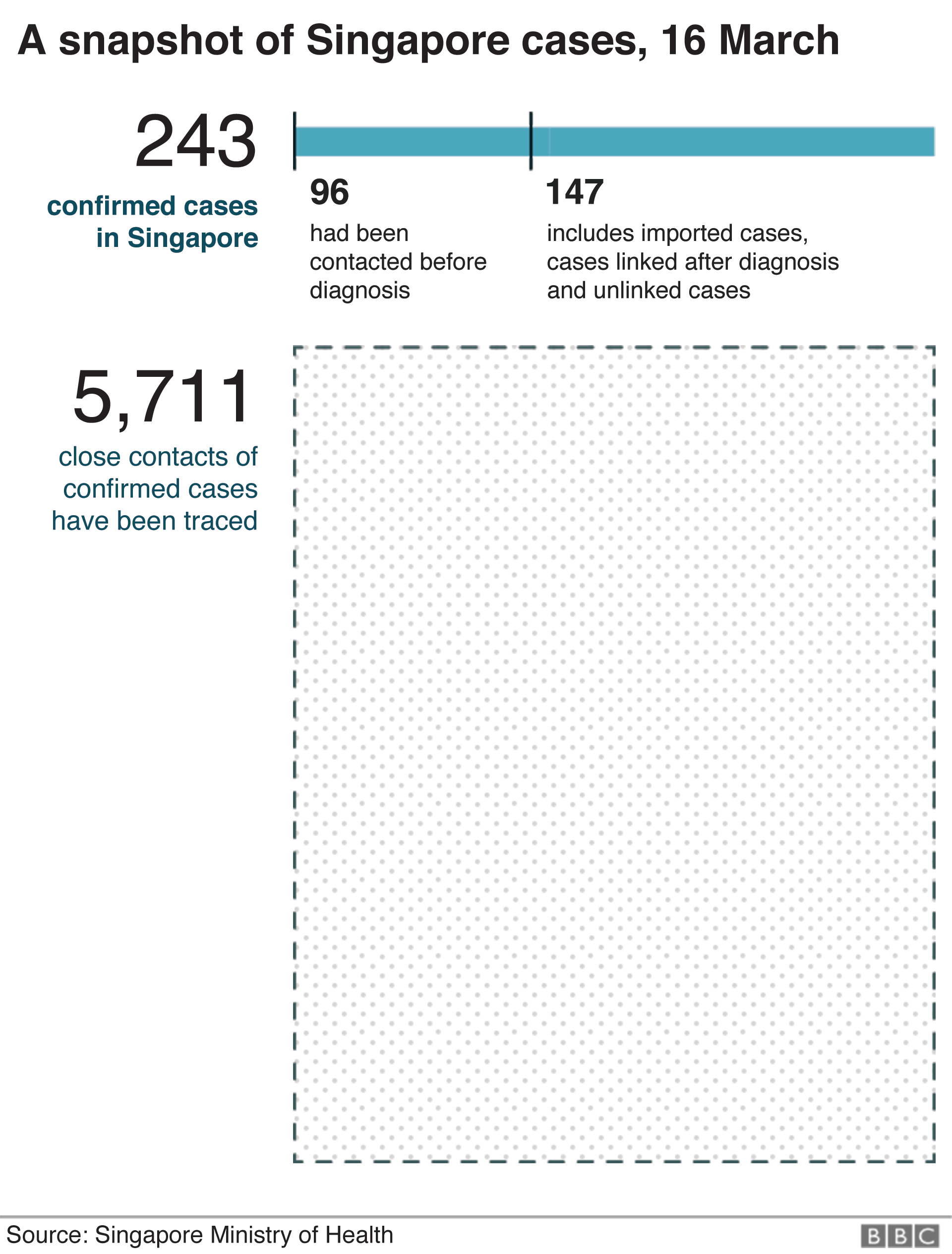

As of 16 March, Singapore had confirmed 243 cases and no deaths. For about 40% of those people, the first indication they had was the health ministry telling them they needed to be tested and isolated.

In total, 6,000 people have been contact traced to date, using a combination of CCTV footage, police investigation and old fashioned, labour-intensive detective work – which often starts with a simple telephone call.

A call from a stranger

It was one of those calls on a sunny Saturday afternoon during a barbecue that led to Singapore-based British yoga teacher Melissa (not her real name) learning she was at risk of contracting the virus.

“It was surreal,” she says, describing the moment an unknown number flashed up on her phone.

“They asked ‘were you in a taxi at 18:47 on Wednesday?’ It was very precise. I guess I panicked a bit, I couldn’t think straight.”

Melissa eventually remembered that she was in that taxi – and later when she looked at her taxi app realised it was a trip that took just six minutes.

To date, she doesn’t know whether it was the driver or another passenger who was infected.

All she knows is that it was an officer at Singapore’s health ministry that made the phone call, and told her that she needed to stay at home and be quarantined.

The next day Melissa found out just how serious the officials were. Three people turned up at her door, wearing jackets and surgical masks.

“It was a bit like out of a film,” she says. “They gave me a contract – the quarantine order – it says you cannot go outside your home otherwise it’s a fine and jail time. It is a legal document.

“They make it very clear that you cannot leave the house. And I knew I wouldn’t break it. I know that I live in a place where you do what you’re told.”

Two weeks later, Melissa had shown no symptoms of Covid-19 and could leave her house.

In Singapore, most people know somebody who has been contact traced and that is part of the point. With almost 8,000 people per sq km it’s one of the most densely populated countries on Earth. An unidentified infected cluster could spread the disease rapidly.

The potential strain on the economy and health service could be huge. Singapore had little choice but to try to find and isolate everybody at risk.

Detectives solving a puzzle

Conceicao Edwin Philip is one of three contact tracers at Singapore General Hospital, one of the government hospitals responsible for treating coronavirus patients.

His team is the first to talk to patients when they come to hospital, to find out who they’ve been in contact with and where they’ve been.

“Once we get the results from the labs [of a positive case] we have to drop everything and push through the night till about 3am. The next day, you start again,” he says.

They hand that vital information to staff at the Ministry of Health who continue with the process.

“Without this first piece, nothing can be connected. It is like a puzzle, you have to piece it all together,” he says.

Zubaidah Said leads one of the Ministry of Health teams tasked with that next job.

Often her teams face challenges gathering information – some patients are too sick to answer for instance – and that makes their job much harder.

“As far as possible for such cases, we will try to have second information, but again that has been difficult” she says.

That is where the next team comes in, because Singapore also has the advantage of having police criminal investigation units on the case.

“The police and the ministry hold daily teleconferences to exchange information,” senior assistant commissioner (SAC) of police Lian Ghim Hua, of the Criminal Investigation Department told the BBC via email.

“An average of 30 to 50 officers are working on contact tracing on any given day, and the number has scaled up to over 100 officers at times.”

The contact tracing is done on top of the police’s daily duties – something made possible by Singapore’s low crime rate.

On occasion officers have also roped in assistance from the criminal investigative department, the narcotics bureau, and the police intelligence services.

They use CCTV footage, data visualisation and investigations to help them trace contacts whose identities aren’t known in the first instance, for example a taxi passengers who did not make an app booking, or paid by cash.

The effectiveness is clear from the case of Julie, who went to hospital feeling dizzy and feverish in early February.

Less than an hour after doctors told her she had contracted the virus, the system kicked in.

“I was on my hospital bed when I got the call,” she said. What followed was a meticulous questioning of everything Julie had done and everyone she had met over the last seven days.

“They wanted to know who I was with, what I was doing, what their names were and then their contact numbers.

Officials were looking for close contacts, typically someone who spent more than 30 minutes with the infected person, within a 2m space.

“There was no interest in someone I had brushed shoulders with even if it was someone that I knew. They were looking for people I had spent some amount of time with.”

Julie spoke to the contact tracer for almost three hours. At the end of that phone call, she had identified 50 people. All were contacted by the Ministry of Health, and served 14-day quarantine orders.

Not one developed the virus.

The ‘gold standard’

Contact-tracing isn’t new – it’s been used for decades to track patients who may have passed their illness to others during their stay.

But Singapore’s use of the system during this crisis was praised by Harvard epidemiologists in early February, who described it as a “gold standard of near-perfect detection”.

The World Health Organization has also praised Singapore for being proactive even before the first case was detected.

Singapore, unlike the US and much of Europe, started contact tracing early to stay ahead of community spread.

“If you leave it too late then everything becomes so much harder to do, because there are so many cases,” says Dr Siousxie Wiles, associate professor at the University of Auckland in New Zealand.

But the level of precision and detection used in Singapore would not be possible in most countries.

There are not many nations that have the level of surveillance Singapore has, which the WHO told the BBC in an email, “has allowed for the rapid identification and management of cases”.

That’s coupled with largely compliant behaviour from the general population – when the government calls and asks you questions, it is a near-certainty that everyone will co-operate.

Singapore’s Infectious Diseases Act also makes it illegal for anyone to refuse co-operation with the police in their attempts to gather information.

The penalty is a S$10,000 ($6,900; £5,800) fine, prison for six months – or both.

Two Chinese nationals have already been charged under the act for giving police false information about their whereabouts during contact tracing. No wonder, Mr Conceicao notes, in almost all of cases people are extremely accommodating.

“To use police for contact tracing in this manner of investigating is quite unique to Singapore,” says Chong Ja Ian, an associate professor at the National University of Singapore.

“But in Singapore, this is something people are exposed to and are familiar with. Singaporeans have grown up and lived with a highly surveilled society, so it’s become normalised for them. The sort of reach that the state has is not questioned as much, it’s taken for granted. People have learned to live with this.”

Taiwan, Hong Kong, South Korea have all seen varying levels of success over the last week, using different strategies from big data, social distancing and mass testing to get numbers under control.

Contrast that with other Asian countries with large populations, poor healthcare and detection systems like Indonesia, and that means trying to find those infected is like looking for a needle in a haystack. They have no idea where the next case is coming from.

“Societies which have strong technocratic elites able to conduct long-term planning and relatively high levels of trust in experts and governments are responding better to the virus outbreak” says James Crabtree, associate professor of practice at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore.

“Hence why Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan seem to be coping better than Italy and the US.”

When should you give up?

On 5 March, Singapore announced its latest – and what would become its biggest – cluster so far.

A late Chinese New Year dinner at a community club on 15 February hosted hundreds of people – that one party has yielded 47 infections so far.

They have gone on to infect others in the community, raising fears that contact tracing is fast becoming irrelevant, and that other, more stringent measures need to be enforced like school closures and lockdowns.

Singapore is also seeing an exponential rise in the number of new cases per day – most of them imported. On 18 March, for example, it announced 47 new cases – 33 were imported, mostly Singaporeans who had returned home.

It has imposed restrictions on travellers entering the country as a result.

The government says there is still value in contact tracing, because the data it collects from contact tracing helps policy makers decide which strategy to roll out at different phases of the epidemic, says Dr Said.

“Until we reach a stage where the numbers are so high it overwhelms our entire ability to bring sources in to try and contain outbreaks as they arise that may be a time when we have to think about changing our strategy,” Kenneth Mak, Singapore’s deputy director of medical services says.

“But we don’t see that as something that we need to consider very seriously at this point in time.”

Almost two months into the outbreak, there have been no deaths in Singapore.

Singapore has credited that to its healthcare services but also its contact tracing.

It has bought time, so doctors could treat the people in hospital who really needed treatment, without overwhelming healthcare services the way it happened in Wuhan.

The reality is that Singapore will have to give up contact tracing if numbers continue to rise. It is expensive, labour intensive and at some point the virus will overtake the contact tracers.

But until then it is a race against an invisible offender. The tracers know it just takes a few more untraceable cases before the virus begins surging through the population.