In the mid-1980s, as a group of American archaeologists pored over satellite images showing Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, they did not know what to make of one unexpected pattern: a near-perfect ring, about 200km across.

Cenotes, the blue water sinkholes that are a staple of Yucatan tourist brochures, dot this arid landscape, opening up seemingly at random as you trek across the vast flatlands of the Yucatan, a dogleg of low, dry forest on Mexico’s eastern edge. But seen from space, they cluster together to form a pattern: an arc, articulating nearly half a circle, as if a drawing compass had been stuck into the map on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico and spun around until running out of land.

Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula is famous for its cenotes, blue water sinkholes that dot the arid landscape (Credit: Simon Dannhauer/Alamy)

The archaeologists had discovered the pattern, which encircles the Yucatecan capital, Merida, and port towns of Sisal and Progreso, while trying to understand what had become of the Mayan civilisation that had once ruled over the peninsula. The indigenous Maya had depended on the cenotes for drinking water, but the uncanny circular arrangement of the holes perplexed the researchers as they presented their findings to fellow satellite specialists at a scientific conference Selper in Acapulco, Mexico, in 1988.

For one scientist in the audience, Adriana Ocampo, then a young planetary geologist at Nasa, the circular formation sounded a klaxon she had been trained to anticipate.

Ocampo, now 63, explains that she saw not just a ring, but a bullseye.

“As soon as I saw the slides that was my ‘Aha!’ moment. I thought ‘This is something amazing’. ‘This could be it’,” said Ocampo, now director of Nasa’s Lucy programme, which will send a spacecraft into Jupiter’s orbit in 2021. “I was really excited inside but I kept cool because obviously you don’t know until you have more evidence.”

Approaching the scientists, heart pounding, Ocampo asked if they had considered an asteroid impact – one giant and violent enough to have scarred the planet in ways still being revealed 66 million years on.

“They didn’t even know what I was talking about!” she laughed, three decades later.

In the mid-1980s, a group of archaeologists discovered that Yucatan’s cenotes formed a near-perfect ring, about 200km across (Credit: NASA Image Collection/Alamy)

Ocampo’s chance encounter was the beginning of a scientific correspondence that would establish the foundations for what most scientists believe today: that this ring corresponds to the edge of the crater caused by an asteroid 12km wide, which struck the Yucatan and exploded with unimaginable force that turned rock to liquid.

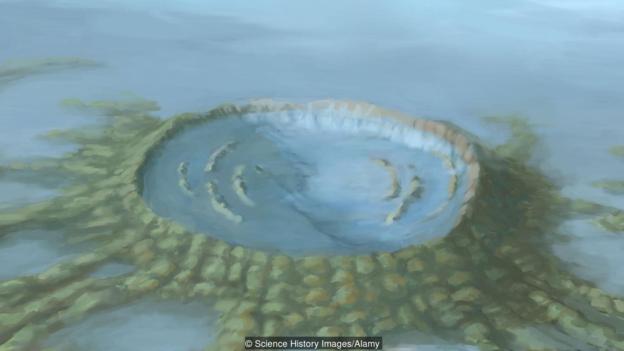

Since the early ‘90s, teams of scientists from the Americas, Europe and Asia have worked to fill in the remaining blanks. They now believe the impact instantly created a crater 30km deep, causing the Earth to act like a pond after a pebble is dropped, rebounding up in the centre to create a mountain – just for a moment – reaching twice the height of Mt Everest, before crashing down. In the years that followed the cataclysmic impact, the world would have changed beyond recognition, with the plume of ash blocking the sky and creating perpetual night-time for more than a year, plunging temperatures below freezing, and killing off about 75% of all life on Earth – including almost all the dinosaurs.

Today, that centre point, the place where that imaginary compass stuck and the mountain once rose, is a buried a kilometre below a tiny town called Chicxulub Puerto.

Scientists believe that the ring corresponds with the edge of a crater formed by an asteroid impact that occurred 66 million years ago (Credit: Science History Images/Alamy)

When I visited that settlement of a few thousand people, low-rise houses painted yellow, white, orange and ochre surrounded a type of modest town square that makes up the area’s many photogenic but unremarkable Yucatecan villages. The town has had so little publicity that the few dinosaur-lovers who do try to make their way in pilgrimage along the Yucatan’s long, twisty roads between prickly scrubland forest often end up lost in another nearby town called Chicxulub Pueblo, half an hour’s drive inland.

Even if they reach the correct town, located 7km east along white-sand coastline from the popular holiday resort of Progreso, there are few indications that this was the scene of one of the most consequential and disastrous acts of the last 100 million years of Earth’s history. Stroll around the main square and you’ll catch sight of paintings of dinosaurs by local children. There is a playground nearby where climbing frames and slides are topped with hard plastic sauropods in primary colours. The only monument, in front of the church on the main square, takes the form of a cartoonish bone, made from concrete, laid in front of an altar like plinth depicting dinosaur species.

Until Ocampo’s findings were published in 1991, this area of the Yucatan had been the subject of little international interest. Today, there is a museum, opened in September 2018 between Chicxulub Puerto and the Yucatan capital Merida, 45km to the south). The Museum of Science of the Chicxulub Crater, a joint project by the Mexican Government and the country’s biggest university, National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), aims to take people back to the moment, 66 million years ago, when the 12km asteroid changed world history, ending the reign of the giant beasts that had lasted millions of years. And by boosting local awareness of the cataclysmic events that took place here, the museum hopes to begin the process of bringing tourists to explore the Yucatan’s prehistoric past, which overlaps with popular Mayan historical destinations like Chichen Itza and the party city of Cancun.

It is believed that the asteroid impact would have wiped out 75% of all life on Earth, including almost all of the dinosaurs (Credit: Science Photo Library/Alamy)

Chicxulub Puerto and its surrounds deserve to be better known worldwide, says Ocampo, who was born in Colombia but moved as a child to Argentina, arriving in the US at age 15. The asteroid, although bringing unimaginable violence to this area, benefitted one species above all others: humans, who, millions of years later, would evolve into the ecological gap created by the destruction of the world’s biggest predators.

Without that impact, humanity might well have never existed.

“It gave us a leg up to be able to compete, to be able to flourish, as we eventually did,” she said.

Ocampo’s discovery came at the end of a decade-long quest for the location of the asteroid impact. The key to her ‘Aha! moment’ had been an intuition she’d picked up after working with a legendary figure in space science, Eugene Shoemaker. Shoemaker – the pioneering American geologist who is credited as one of the founders of the field of planetary science and remains, 21 years after his death, the only person whose ashes are buried on the Moon – had instructed her that near perfect circles were unlikely to have been caused by other terrestrial forces, and could provide clues to Earth’s geological development.

The small, coastal town of Chicxulub Puerto is believed to be the centre of the impact crater (Credit: Adamcastforth/Wikimedia Commons)

The idea that a giant asteroid had wiped out the dinosaurs was proposed by Californian father-son duo Luis and Walter Alvarez in the early 1980s. “But, then, it was extremely controversial,” Ocampo said. What she did was to place one of the final connecting jigsaw pieces that began linking scattered ideas between scientists who were working independently with fragments of information, often on overlapping investigations.

For example, as early as 1978, geophysicist Glen Penfield, working alongside Antonio Camargo-Zanoguera for Mexico’s national oil company Pemex, had flown out over the Caribbean waters that lap the shore at Chicxulub Puerto. Using a magnetometer, he scanned the waters looking for signs of oil, instead finding the underwater half of the huge crater. But that evidence belonged to Pemex, so was not made available to the scientific community.

In fact, the first person to connect the Yucatan ring with the Alvarez asteroid theory was a Texan journalist named Carlos Byars who wrote an article for the Houston Chronicle in 1981 asking if the two were linked. Byars later shared his theorywith a grad student named Alan Hildebrand, who then approached Penfield after examining a rock layer in Haiti, and it was the two of them who determined that the crater wasn’t a volcano, but an asteroid impact. “[Byars] gets the credit for being the first to put the pieces together – a newspaperman!” Ocampo said. “It’s an amazing story when you put all the pieces together.”

Texan journalist Carlos Byars was the first person to connect the Chicxulub Crater with the theory that an asteroid wiped out the dinosaurs (Credit: Graham Prentice/Alamy)

But the story is not simply one of history, it could also give us insight into life beyond Earth. Lessons learned in the asteroid crater have informed research by Nasa’s Curiosity rover, which touched down on Mars in 2012 and has spent the last six years investigating the Martian environment and geology.

Debris discovered from asteroid impacts on Mars compared with ejecta from the Chicxulub Crater shows similarities that indicate that Mars must once have had much thicker an atmosphere than it does now – one closer to the atmosphere that supports life on Earth. “It’s important for us to know what happened in the past to be prepared for the future,” Ocampo said. “It provides a really good insight into what has happened in the geological evolution of Mars.”

The Chicxulub Crater has been nominated for recognition as a Unesco World Heritage site (Credit: Reinhard Dirscherl/Alamy)

But, in the Chicxulub Crater, much of the incredible knowledge remains buried below ground, rarely recognised by visitors or locals despite the opening of the museum and Mexico’s application to have the crater recognised by Unesco. There is precious little for visitors to see as the impact was so long ago. Tourists who do visit one of the few remnants – the stunning cenotes, where you can swim among fish and dangling tree roots – may be unaware that these geological features exist only because rock was forced to the surface from deep underground during the impact. Over thousands of years, dripping water has cut through the limestone at this faultline to carve out the sinkholes.

Ocampo has visited the peninsula numerous times since her discoveries there in the late 1980s, but when asked if people are aware of the importance of this place, she responds unhappily.

“The short answer is no,” she replied. “We need to do better. We need to educate, we need to make them aware of the extraordinary ground that they are living on.”

“They [local people and authorities] are trying to raise the knowledge base and it would be wonderful to help,” said Ocampo, who is also a proponent of planetary science education in Latin America. “It is a unique place in our planet. It truly is.”

“It should be preserved as a World Heritage site.”