When tech historians of the future look back at 2018, it may stand out as the year that the wheels came off Facebook or at least its original platform.

Instagram, WhatsApp and Oculus all had their troubles but managed to escape the year without seeing their brands trashed in quite the same way as their parent.

So, it’s no surprise to see articles related to Facebook’s various scandals secured it three of the spots in BBC Tech’s most-read stories list for 2018.

Two other controversy magnets – Elon Musk and Huawei – however, narrowly missed out.

And for the first time since we started compiling this list in 2012, none of the placings went to a product launch.

Below are the most clicked on articles for each month of the year – a mix of controversy, endeavour and sparkly revenge.

Software flaws have long been a bane of computing, but when news emerged of serious vulnerabilities in popular processor chips there was a serious intake of breath from the cyber-security community.

Billions of PCs, smartphones and other devices were said to be susceptible to the Meltdown and Spectre bugs – including, as it emerged, Apple’s products.

At one point there was talk of owners having to brace themselves for their machines feeling noticeably more sluggish as a result of the workarounds that would be needed, or even needing to send their computers in for component swap-outs.

A year on, there doesn’t appear to have been any malware related to the flaws reported in the wild, even though further variants of the originally disclosed exploits have been discovered.

And as far as personal computers are concerned, the patches released don’t appear to have caused much of a hit to performance.

Deepfakes gave the internet something else to worry about in February, after it emerged that free software meant anyone could replace the face of one person with another’s in video footage so long as you had enough photos of the latter.

Inevitably, the tool was used to create pornography with a range of predominantly young female celebrities’ features generated to supplant those of the original adult actresses. One after another websites lined up to ban the content until Reddit, which had been home to much of it, decided to do likewise.

As the algorithms involved have improved, there has been much discussion about the danger of fake news creators adopting the face-mapping technique to create bogus videos of politicians.

But there’s another worrying trend.

It appears that some Deepfakers are attempting to scrape social media for images of acquaintances that they can turn into pornography, and have been sharing details of their progress in chat forums.

Donald Trump’s election in 2016 helped put Cambridge Analytica in the public eye after reports that its psychological profiles of US voters had helped his campaign target messages.

But the London-based consultancy only became a household name after a report in the Observer explained how the firm had made use of millions of harvested Facebook accounts’ details, while a follow-up Channel 4 TV report recorded the consultancy’s chief on tape discussing how beautiful girls could be sent to a politician’s house as a honey-trap.

Facebook also found itself in the firing line. It didn’t help itself by first trying to suppress the story and then quibbling over whether it warranted being described as a “data breach”.

Yesterday @facebook threatened to sue us. Today we publish this.

Meet the whistleblower blowing the lid off Facebook & Cambridge Analytica. https://t.co/QcuBJfBU5T— Carole Cadwalladr (@carolecadwalla) March 17, 2018

When Mark Zuckerberg did finally apologise several days later, he made a promise that has been repeatedly thrown back at him since.

“We have a responsibility to protect your data, and if we can’t then we don’t deserve to serve you,” he said.

By early April, Facebook was estimating that up to 87 million of its members’ details had been improperly shared with Cambridge Analytica. More than a million of them were thought to belong to UK-based users.

This was based on the number of accounts that an academic at the University of Cambridge – Dr Aleksandr Kogan – had harvested from the social network via a personality quiz.

Soon after, Cambridge Analytica responded that its parent, SCL Elections, had in fact “only” licensed 30 million people’s records from Dr Kogan, and all, it said, had been from US citizens.

That wasn’t enough to save it – the political consultancy folded in May.

But it now forms part of Facebook’s defence against a fine from the UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office, which was imposed despite the watchdog acknowledging that it had found no evidence that UK citizens’ data had been passed to Cambridge Analytica.

The £500,000 amount is peanuts to the social network – it makes more in half an hour, and the reputational damage it has incurred has arguably been far more costly.

But Facebook is concerned that the penalty could set a precedent for other data regulators to follow.

The British video games critic John “TotalBiscuit” Bain had first told his fans and wider following that he had cancer in 2015.

By April 2018 the 33-year-old had announced he was retiring from journalism as the medication he was on was preventing him from thinking clearly.

Even so, his death shocked and saddened many of his 2.2 million YouTube fans when it was confirmed.

The obituaries that followed mostly focused on how he had championed indie games and criticised some of their bigger-budgeted rivals, which he had said sometimes prioritised profit over all else.

But on social media and in some later articles, there was criticism of the role Mr Bain had played in the GamerGate movement.

It was claimed he had given legitimacy to a misogynistic campaign that had been responsible for the harassment of others.

But this in turn spurred on his supporters to defend his legacy. They said his involvement had been mischaracterised and noted that Mr Bain had called for ethics in games journalism for several years before GamerGate existed.

The phrase “the cloud” conjures up images of our data being stored in some nebulous form high above us.

In reality, tech firms are investing billions of pounds in racks of computer servers housed in gigantic data centres across the globe to power the apps we use and internet services we call on.

For the most part, these are built at ground-level. But in June, Microsoft sank an experimental data centre into the sea off Orkney in the north of Scotland.

The idea is to reduce cooling costs by keeping the equipment in a sealed vault underwater.

The tech giant intends to monitor Project Natick for five years to see if the scheme is a practical proposition for a wider rollout.

But elsewhere, Google revealed it had already made the switch to liquid-cooling to tackle the heat given off by its latest artificial intelligence-focused computer servers.

But rather than dropping its equipment overboard, it is piping coolant to each chip.

PayPal was guilty of a major faux pas when it wrote to Lindsay Durdle, one of its recently deceased customers, to say her death was a breach of its rules.

To make matters worse, it added that it might take legal action as a consequence.

Her husband Howard Durdle was appalled, and to be fair so was PayPal’s PR team when the BBC brought the matter to its attention.

Although the firm was unable to confirm exactly what had gone wrong it attempted to make good on the situation by writing off a debt his wife had owed.

“PayPal have been in touch, have apologised sincerely and have promised to change whatever they need to internally to ensure this can’t happen again,” Mr Durdle tweeted after the BBC’s article was published.

“I just hope more organisations can apply empathy and common sense to avoid hurting the recently bereaved.”

As official statements go, the US State Department’s wasn’t the most reassuring: “We don’t know for certain what it is and there is no way to verify it.”

The subject was a Russian satellite that had been launched 10 months earlier and was displaying abnormal behaviour.

One US official suggested it could be a space weapon designed to destroy other satellites – an allegation a Russian diplomat slammed as being “unfounded [and] slanderous”.

For those who track such developments, the US’s suspicions echoed those raised about another Russian launch four years earlier when what was thought to be a bit of debris started zipping about in orbit.

In any case, at the end of the year we are officially none the wiser about the objects true capabilities.

But with the Trump administration pursuing its own plan to create a Space Force by 2020, off-planet militarisation looks set to remain a hot topic.

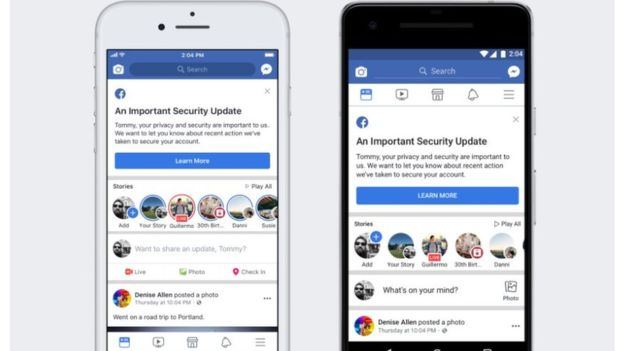

With the Cambridge Analytica scandal still ratting along, Facebook revealed that a separate problem had exposed almost 50 million accounts to being hijacked.

The cause was a vulnerability in the code of its View As privacy facility, which was designed to let users see what their profile looked like to others.

At the time, Facebook said it was “temporarily turning off” the tool while it conducted a review. Three months on, it remains disabled.

The firm did, however, revise its estimate down to 30 million accounts.

While we’re on the topic, here’s some of Facebook’s other controversies in 2018:

being accused by the UN of having played a “determining role” in stirring up hatred against Myanmar’s Rohingya Muslims

being sued by advertisers who alleged the firm took more than a year to disclose its video view figures had been over-estimated after discovering the problem. Facebook says the complaint is “without merit”

getting into a spat with the philanthropist George Soros after chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg questioned if the billionaire was shorting Facebook’s stock because he had described it as a “menace”

losing WhatsApp’s co-founders over a privacy clash, and then Instagram’s two co-founders because of other tensions

launching first a dating service and then Portal, a video chat device for the home, while still embroiled with its various privacy breaches, leading to suggestions the company was “tone deaf”

having details of its data-sharing practices with other companies revealed via a series of newspaper exposes and a House of Commons parliamentary committee

Mark Zuckerberg telling Congress that he was not familiar with the phrase “shadow profiles” – a term used to refer to information gathered about non-members – despite the fact complaints had been made against the practice since at least 2011

In an end of year message posted yesterday, Mr Zuckerberg said Facebook had become much more “proactive” at addressing the challenges it faced but warned some problems could “never be fully solved”.

But overall, he said he was “proud of the progress” Facebook had made in 2018.

Many of us have experienced the sinking feeling that comes from leaving the home in the morning to discover your smartphone battery never recharged overnight.

Typically, it’s a case of failing to properly plug the handset in. But a YouTuber’s tests of the latest iPhones indicated some of the new devices only topped up their power if their displays were “woken up” first.

Inevitably this was dubbed “chargegate”, and when the BBC published its take on the issue Apple had yet to comment.

But a week later, when it released the next version of its mobile operating system, Apple’s accompanying notes confirmed it had fixed a bug that had caused the flaw.

At the start of the year the Time’s Up movement was founded to take a stand against sexual assault, harassment and inequality in the workplace. It was a response to the allegations against Harvey Weinstein but also marked an effort to tackle problems faced by women more widely.

Eleven months later, seven of Google’s employees declared “time’s up” on the tech giant after accusations of misconduct emerged involving two past male high-fliers as well as dozens of other staff.

As a result, workers at Google’s offices across the world staged a series of walkouts. Managers were delivered a set of demands, including a call to end the firm’s requirement that sexual harassment disputes be dealt with internally.

About a week later, Google’s chief Sundar Pichai confirmed that the business would indeed stop its policy of forced arbitration, opening the door to it being sued over the matter in the future.

The internet fell in love with a revenge prank staged by an ex-Nasa engineer earlier this month.

After having a package stolen from his porch, Mark Rober constructed a “bomb” that married a centrifugal motor, lots of glitter, fart spray and several smartphones.

He then hid the device within an Apple Homepod speaker box and left it on his porch.

When thieves subsequently stole it, it recorded the moment it sprayed them with its contents. After which, Mr Rober retrieved the package and repeated the exercise.

In an ideal world, the story would have ended there, with Mr Rober’s YouTube fame assured thanks to the compilation video he made.

But a couple of days after uploading the footage, the inventor replaced the video with a shorter edit.

Some viewers had voiced suspicions about parts of the footage, and Mr Rober acknowledged that when he had chased up their concerns he had discovered that one of his helpers had recruited acquaintances to pose as two of the five featured thieves.

An important note: pic.twitter.com/9MgQFVbhoB— Mark Rober (@MarkRober) December 20, 2018

“I’m especially gutted because so much thought, time, money and effort went into building the device and I hope this doesn’t just taint the entire effort as ‘fake’,” he tweeted.

Most viewers seem to have been forgiving, but it’s unfortunate that what was a fun stunt might cause many to be more suspicious and cynical about what they see online in the future.